The Takaichi administration has declared a Trump-like war on commercial solar power. The Liberal Democratic Party (LDP) announced that it intends to end all subsidies for megasolar and for all ground-mounted solar over 10 KW, starting in fiscal 2027. Beyond that, the government will now require that any new projects be certified as safe. That seems a proper response to mudslides at some hillside megasolar farms, but only if safety is not used as a pretext for blocking solar.

Informed sources told me that these moves came from Prime Minister Sanae Takaichi and her Diet allies, not the Ministry of Economy, Trade, and Industry (METI). Officials there have been debating whether it was time to reduce or eliminate subsidies, but had not decided.

The war on solar strikes another blow to Japan’s per capita growth and living standards. It also makes it virtually impossible for Japan to meet its 2030 goals for renewable energy and emissions reduction. Utilities had already warned of electricity shortages down the road as Artificial Intelligence drives demand for electricity to soar. Slowing growth in solar energy will heighten that risk. Worse yet, as detailed below, the reasons given for the subsidy removal seem flimsy.

While cutting aid to solar, the government will keep providing massive subsidies for fossil fuels. In 2025, according to Climate Integrate, 38% of government spending on energy and “decarbonization” was devoted to projects that prolong the use of fossil fuels: gasoline subsidies, carbon capture and storage (CCS), and co-firing gas and coal power plants with hydrogen and ammonia. Only 4% was dedicated to renewables.

Making 2030 Renewable And Emissions Goals Impossible

Solar power soared after the Fukushima disaster when the Democratic Party of Japan (DPJ) government introduced hefty subsidies via the “Feed-in-Tariff.” Yearly additions to solar capacity peaked at 10.8 gigawatts (GW) in 2015. Then Shinzo Abe replaced the FIT with a weaker measure, the Feed-in-Premium (FIP). Consequently, new solar capacity steadily decelerated. Only 2.5 GW was added in 2024 (see chart below). At that rate, Japan can't reach its 2030 renewable energy goal—36-38% of all electricity—since solar alone would have to increase by 3.5-to-5.4 GW every year. Takaichi’s move will further shrink solar growth. Hence, Japan will also miss its emissions reduction goal.

Even before the subsidy abolition was announced, the organization for Cross-regional Coordination of Transmission Operators (OCCTO), a federation of utilities, said that its member companies would reach only 30% renewables in 2029, while coal would still supply 25% as late as 2034.

How The War On Solar Hurts The Economy

The economy will be hurt in two ways. First, Tokyo will be forcing a shift to higher-cost, emissions-intensive sources, like coal and gas. Few experts believe Japan can restart as many nuclear plants as the government predicts.

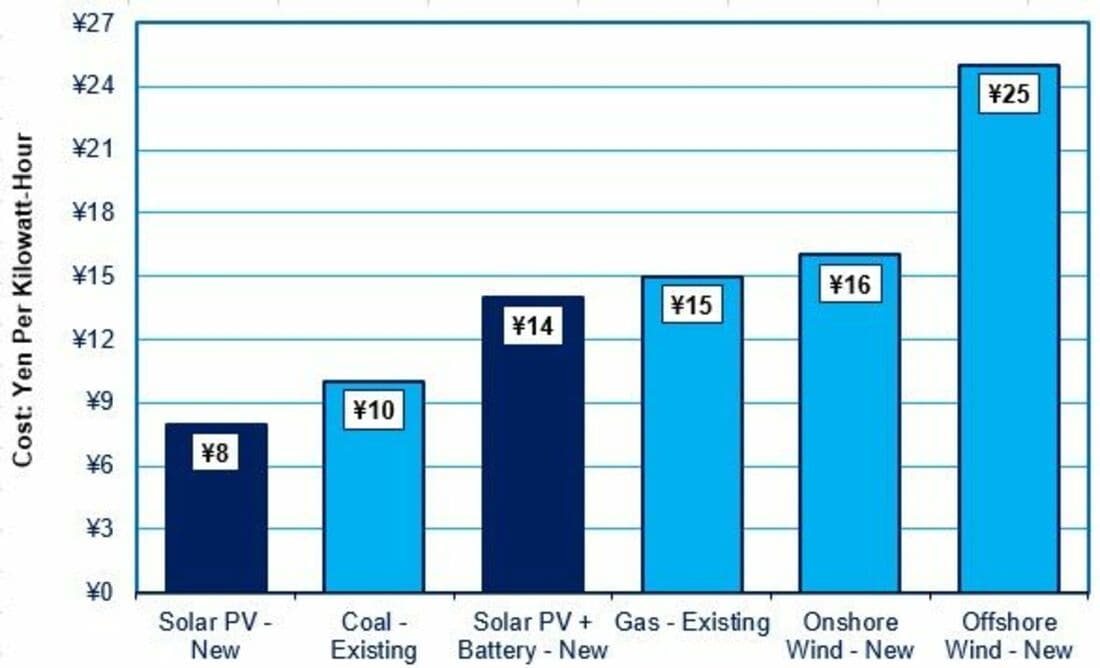

Already, building and operating new solar power plants in Japan costs less than operating existing coal-fired power plants. Add the cost of new battery storage so solar can provide reliable energy all day, and it still costs less than just operating existing gas plants (see chart below).

Over the next decade, solar’s advantage will multiply as its cost drops by another third and battery storage costs halve. Expensive and dubious techniques being promoted by the government—like co-firing with ammonia and/or hydrogen and CCS—will widen the cost gap. Low cost is why, in 2024, solar and wind (mostly solar) provided 87% of the entire global increase in electrical capacity.

Currently, Japanese industries pay the same for electricity as their European counterparts, while Japanese households pay 10% less. This comparison is made in Purchasing Power Parity (PPP) dollars to avoid distortions caused by changing currency rates. If growth in solar is hindered, electricity will increasingly cost more in Japan than elsewhere. Beyond hurting households, this will also make Japan’s electricity-intensive sectors like semiconductors, autos, and machinery less competitive, thereby hurting growth. Since Takaichi prioritizes autos and semiconductors, her policy seems self-defeating.

Now, consider the mammoth increase in electricity demand driven by the advent of Artificial Intelligence (AI) and accompanying data centers. Already, given Japan’s lag in software, the country spends more on importing digital services than on fossil fuels. Depending on how much Japan employs AI and how much it eventually adopts electric vehicles, etc., OCCTO predicts electricity needs could grow as much as 25% by 2040 and 40% by 2050. That would require massive investments in power plants, battery storage, and grid upgrades, including interregional connections. Since new nuclear plants are prohibitively expensive, cutting solar and wind means even more costly and dirty coal and gas. Tokyo talks of “clean coal,” but, according to the International Energy Agency, emissions from Japan’s ultrasuper-critical coal plants are 70-85% as high as the dirtiest “subcritical” plants.

If Japan fails to expand its electrical capacity sufficiently, that will hamper AI, data centers, and other assets essential to economic growth. Yet if it expands without sufficient renewables, both emissions and electricity prices will soar.

Hundreds of leading global companies have pledged to follow “Scope 3” rules requiring them to buy inputs only from companies that use 100% renewable energy after 2030. Back in 2020, SONY, Nissay Asset Management, Kao, and Ricoh warned then-Minister Taro Kono that failure to lift renewables to 40% of electricity by 2030 could force them to move more operations offshore.

So, Why is Takaichi Doing This?

While Takaichi’s predecessors may have moved too slowly on promoting solar power, due to pressure from the nuclear and fossil fuel lobbies, Takaichi seems positively hostile. “We strongly oppose covering our beautiful country with foreign-made [i.e., Chinese] solar panels,” she declared.

Takaichi claims solar is unsafe because it makes Japan dependent on China. But Japan didn’t shut down its auto industry to avoid importing rare earths from China. Instead, METI helped develop other sources. India is becoming a major producer and exporter of solar modules, but still relies on China for upstream components. So, why not help India develop further?

Officials claim rooftop solar can fill the gap. While it is necessary, rooftop solar costs much more than utility-scale solar and also relies on imported panels.

To discount the damage to the economy, Takaichi is also peddling fantasies. She talks of commercial fusion power by the 2030s, a notion scoffed at by experts. She also claims perovskite-based solar power will be commercially viable by the mid-2030s. Perovskites are a thin mineral-based film that can be applied to windows and building facades. Experts like the Institute for Energy Economics and Financial Analysis say that, even by 2040, costs will still be too high for mass use.

Politicians also point out the environmental damage caused by building 20% of Japan’s 9,200 solar sites in deforested locations prone to mudslides. There have been more than 230 accidents at such sites. One of them destroyed 120 homes. However, even without solar, Japan suffers more than 1,000 mudslides each year. A 2018 calamity in Western Japan, which killed 200 people, was caused by torrential rains exacerbated by climate change. Deforesting land for solar adds to the risks.

Voters seem ambivalent. While 12% of municipalities have enacted ordinances restricting solar siting, 74% of municipalities have enacted ordinances promoting renewable energy. Tokyo and Kawasaki now require rooftop solar on new buildings.

But why are any solar farms being built in hazard-prone places? Japan’s leaders claim it’s because Japan has so little flat land. In reality, the Renewable Energy Institute reported in 2020 that there was already enough abandoned farmland to generate 112 GW of renewable capacity. That equals a third of Japan’s total electric capacity. By 2030, the Agriculture Ministry says abandoned farmland could triple to 30% of all farmland. Nonetheless, a government official told me that Japan’s land-use laws preventing the use of this farmland cannot be used because Japan lacks food self-sufficiency. But I don’t believe abandoned land produces any food. Taro Kono has repeatedly complained about these land-use laws.

These land-use laws are among the primary reasons solar and wind are pricier in Japan than elsewhere. Building on forested mountainsides increases acquisition and construction costs. In addition, utilities charge renewable producers higher connection fees than in other countries.

Finally, some argue that solar power no longer needs subsidies, but they defend continued fossil fuel subsidies. In any case, the cost of the necessary grid and battery infrastructure means financial aid is required for several more years.

70% Renewables by 2035 Can Be Done

Post-Fukushima subsidies helped solar capacity grow from almost nothing in 2010 to 10% of electricity output by 2024. That still leaves Japan with the lowest share of renewables among the Group of Seven countries.

Several studies estimate that, by 2035, 80-90% of Japan’s electricity could come from zero-emission sources. For example, America’s Berkeley Lab says 70% could come from renewables, 20% from nuclear power, and the remaining 10% from natural gas. Coal would be completely phased out. A shortfall in nuclear power could be made up for by LNG. This would reduce electric power emissions by 94% and national emissions by almost a third. Moreover, it would cut electricity costs by 6% compared to 2020, even with the necessary infrastructure investments.

Several years ago, hundreds of leading energy-consuming corporations formed new organizations like the Renewable Energy Institute, the Japan Climate Initiative, and the Japan Climate Leaders’ Partnership that pushed for as much as 50% renewables by 2030 and an impactful carbon tax to help achieve it. Today, they feel it’s politically safer to keep a low profile. Unless these powerful groups show some resistance, it will be much harder to reverse the war on solar.