The one Japanese knife I own is an inheritance. In all truth it was a parting gift passed on to me seven years ago from a fellow English teacher moving out of her apartment in rural Kagoshima, Japan. She pulled out the knife from a cabinet under the sink and offered me the dark, burnished wooden handle. There was a moment of hesitation as she let go, finally exposing the blade, rusted from tip to heel.

I was entrusted with the knife under the condition that I would take better care of it than the previous owner and happily promised to abide.

This one knife has served me well over the years and not just in the kitchen. It became a catalyst of culinary adventure and has truly enriched my life as a home cook, but also as a student of the Japanese language and as an admirer of Japanese craft.

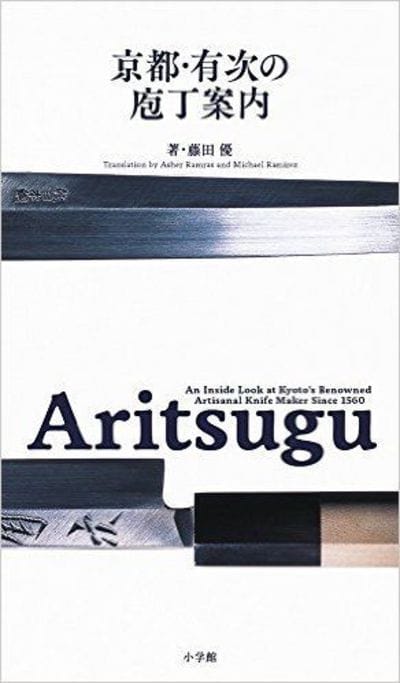

Recently, I had the distinct honor of teaming with the Aritsugu knife company in Kyoto to translate a book showcasing their knives, history and commitment to their tradition of craftsmanship. Having been exposed to the name and learned about the prestige of Aritsugu while studying Japanese cookery, the invitation to participate in the project was a dream come true and has proven to be the most enlightening and rewarding encounter of my culinary journey thus far. I cannot help but recall the anecdotes, memories and moments that contributed to my understanding and respect for the illustrious Japanese knife.

I was first captured by the knife’s beauty. The meticulous lines of the thin sleek blade and the subdued palette of wood, bone and steel all came together like a well composed piece of art. I could see the faint difference in coloration on the face of the blade, the aftermath of heating, cooling and arduously pounding layers of carbon steel.

As a student of pottery, I have long admired Japanese earthenware and ceramics, from the organic color and forms of Bizen and Tamba ware to the detailed expressions found in Arita and Satsuma ware. From the Earth to craftsman’s hands, into the fiery heart of the kiln and back again; it’s like material comes alive with the blood, sweat, tears and knowledge of the creators of these simple but eloquent tools.

I carefully took the knife in my hand, like I were unloading a stack of pots after a firing, and felt a balance unparalleled in my experience with other knives. A far cry from the massproduced stamped blades that had once invaded my kitchen drawers, at times the Japanese knife feels like I am not even holding anything, just operating the knife as if it were another appendage.

Tasked with the chore of restoring a seemingly neglected knife, I took the 12 cm, do ublebeveled kodeba knife to a local renaissance man in search of help. We enjoyed sweet potato shochu on the rocks in his air conditioned living room as the whetstone soaked in a bucket of water outside.

In the humid heat of the summer evening, I was shown the basics of how to grip, position and maneuver the knife when sharpening and quickly worked myself into a sweat restoring the cutting edge with the grittier side of the stone and finally refining the shine with the finer side.

With washoku or Japanese cuisine, you need more than just a knife for serious cooking. It was clear that unlike my old stainless knives, I was not going to get away with a few swipes of a honing steel and be on my way. I realized that caring for Japanese steel was not as simple and required much more care and attention.

The challenge of maintaining the knife made it a more valuable tool to me urged me to use it more and keep it in my life rather than just buying another mediocre knife. I invested in my own whetstone, borrowed cook books from the city library and soon my grocery list diversified to include as many different vegetables throughout the seasons as possible.

I learned how to handle and cut each ingredient and knowing that I had a great tool to do the job made cutting vegetables something to look forward to every time I would step in the kitchen. It felt like I was returning a favor to the ingredients by using a well made and maintained tool.

Never have I ever had so much pleasure cutting something as simple as, say, scallions. Before I would struggle with my supermarket knife, producing endless chains of scallions where the knife’s edge was to dull to cut all the way through. The hard, sharp edge of the Japanese knife snips right through the bunch of vibrant, fragrant tubes, yielding hundreds, thousands of green rings to adorn bowls of miso soup. Japanese knives made cooking more fun than it had ever been.

Another door opened after I was taught how to fillet a whole fish. First it was mackerel and pacific saury, then I worked my knife through sardines and horse mackerel. My only experience with filleting fish in America had been with thin, stainless steel knives that depend of the flexibility of the blade to force the fillet from bone, often sacrificing flesh either torn by the blade or left of the spine.

The kodeba I had was like a doctor’s scalpel, designed specifically for the job of parting small fish, and allowed me to delicately peel the fillet off the spine with the fewest and cleanest strokes. I ran into a problem when I almost chipped the blade of my knife trying to dispatch the head of a chinu, black sea

bream, which I caught at the local port.

My local guru let me know that there is always a knife for the job in a Japanese kitchen and kindly lent me his deba knife: a slightly longer, single beveled knife, with a girthy spine. The weight of the deba, I first thought, may be its defining characteristic, helping the blade glide through fish bones, almost like butter.

Also, having grown up with solely Western style knives in my home, the deba was the first singlebeveled knife I had ever used. This feature came as a surprise to me, but after making the final cut along the spine to release the fillets, it all made sense. The single bevel hugs the spine, producing an unmistakable clicking sound as one works the blade toward the tail of the fish. With deba in hand, I was in the zone. Japanese steel, I began to realize, was empowering me in the kitchen, making me feel likes the pros who seek these knives the world over.

My Japanese knife boosted my tenacity to cook and I found myself eating fish with much more respect and little to no waste. With a refrigerator consistently packed to the gills with fish fillets and freshly brewed fish stock, I often hosted meals for friends.

Cooking for these gatherings quickly became a routine, along with keeping a tidy kitchen and a clean home. I would do anything for the warm atmosphere indicative of friends gathering for good food. This was when I started to realize that keeping a good sharp knife affects the cook just as much as the ingredients.

Having a Japanese knife at home encouraged me to learn more about washoku. I hit the streets, became a regular at a number of restaurants in town and befriended many a foodie, always sneaking a peak behind the counter to see the chefs, wielding their Japanese steel. The multigenerational boning knife at the yakitori restaurant is strong and thick enough to power through pig trotters.

Just down the street, the sushi chef painted long strokes with his yanagiba to make a sashimi plate that came to life when it came to the table. Only the sharpness of a Japanese blade, I learned, produces that lively shine on the cut face of the fish and locks in the umami.

When summer came along my friend the postmaster was ecstatic when showed me his custom Kansai style eel knife. The blunted, angular shape was so different from the knives I had seen before and the fact this knife was designed to be used only for eel seemed almost fanatic.

I later enrolled in a cooking class. As I took my place in the tiny kitchen, standing alongside my fellow students I noticed something: everyone had their very own Japanese knife, clean, sharpened and ready to go.

A few weeks into the course we were preparing to m ake a hot pot. I attempted to pare and chop a large hakusai cabbage when a fellow student offered me their nakiri vegetable knife, explaining that the longer, thinner edge of the nakiri is specifically designed to cut vegetables with ease and the least amount of damage to the ingredients.

The leaves of cabbage fell effortlessly at the edge of the nakiri as I experienced first hand, once again, the practicality of the seemingly endless iterations of Japanese knife designs. Reflecting on each class on the walk home, I began to see that washoku and Japanese knives were inseparable: each knife in the Japanese kitchen is intrinsically linked to an individual task.

You can also find the passion of the craftsman in the tools that form and shape the ingredients to the final product. This symbiotic relationship proved to me that washoku was intended to be made with Japanese knives. Otherwise it would be like trying to trim a bonsai with a hairstylist’s scissors.

One encounter in particular that will stick with me forever occurred on a walk I took along Akune City’s old port late one evening years after inheriting my knife. After passing the ice factory and boat launch, I turned off the main drag onto a residential street when I heard the now familiar sound of the scraping and splashing of steel, stone and water.

There in the darkness, barely lit by the kitchen light inside leaking out onto the street, was a man crouched over the gutter with a bucket of water and a whetstone sharpening his trusty knife. The sound of tired children and dishes clanking in the sink were like a melody harmonizing with the rhythmic passes of the knife’s edge over the whetstone.

The end of of another day. I walked slowly, absorbing what I thought to be a special cultural moment in time for a visitor to Japan. It was an image that reinforced my impression of the ubiquity and respect of knives in the Japanese home and a story I enjoy telling fellow fans of Japan.

At the same time this brief encounter forced me to look inward. I wondered: is there any one tool in American cooking culture that has the same significance as a knife in the Japanese kitchen? What first came to mind was classic cast iron cookware. Made of thick steel, black and seasoned to perfection by frequent use and mindful care, a good piece cast iron is a sight to behold in its own right. In some families skillets are passed down through the generations and are a fixture on the stovetop.

Cast iron is also widely respected by professional chefs for its performance, ease of use and longevity. While cast iron may very well be the closest thing to an American culinary tradition, it pales in comparison to the depth, history and craftsmanship that epitomizes cutlery in Japanese culture.

In an age with an ever rising population of conscious, foodloving consumers, the prized, old recipe is now overshadowed by the best, local, organic ingredients and the tools we use to cook are also seeing more welldeserved attention.

As such, the draw of a Japanese knife is only becoming more widespread and is rooted in the allure of Japan’s unbroken tradition of making the best knives in the world. When someone takes a Japanese knife in their hand they are holding a piece of history, crafted with passion, intended to be used with care for the wellbeing of ourselves and those around us. The Japanese knife gifted to me is my piece of living history and I feel proud to have become a part of the tradition as well.