We’ve spilled a lot of ink over the years about the need for corporate reform in order to raise Japan’s growth rate, but one of our readers said we should get specific. If officials or Diet members asked what concrete measures they could take to nurture greater business productivity, what would we suggest?

In this article and next, we will focus on one aspect of corporate reform: entrepreneurship. Can Japan create an economic-business environment in which it is easier for new companies to emerge, and for them to grow sufficiently to challenge and replace incumbent firms? Is Japan’s dearth of entrepreneurialism so deeply embedded in the society, e.g., a risk-averse culture, that it is impossible for policymakers to change it? Or, are there specific measures that could exert a real impact?

We asked these questions of entrepreneurs, “incubators” that promote them, financiers, professors who teach would-be entrepreneurs, and government officials. We are convinced that governmental measures could help, and we’ll detail some of their proposals in the next issue. For now, we want to focus on why high-growth startups are so critical to overall economic growth and on Japan’s dearth of them.

David Birch, an American business consultant, spoke of three types of firms--mice, elephants and gazelles--in a groundbreaking study a few decades ago. Mice are the beauty parlors and “mom and pop” shops. They start off small and will always remain small. “Elephants” are the old-line, decades-old giant firms like General Motors, many of which die, shrink or get taken over. Only 11 of America’s 100 largest firms in 1970 can be found even among the top 500 firms.

“Gazelles” are rapidly-growing, relatively new firms. A 2006 OECD study defined gazelles as enterprises less than five years old that started with at least ten employees and achieved an average employment growth rate exceeding 20% per year over a three-year period. Even though gazelles comprise a small share of OECD economies at any point in time, they regularly provide an outsized share of growth in jobs and GDP and productivity. That’s because they embody new technologies and new ways of doing things.

Gazelles, jobs and productivity

Birch estimated that the gazelles created two-thirds of net new jobs (i.e., jobs created vs. jobs lost). By his estimates, just 4% of US firms created 70% of all net new jobs. Studies of Canada and European countries have found similar results. For example, from 2007 to 2015, General Electric’s workforce in America fell from 140,000 to 125,000. During the same period, Amazon.com’s staff soared from 17,000 to 131,000.

The real contribution of gazelles is that they drive a shift of capital and workers from lower-productivity jobs to higher-productivity ones. Amazon.com is not a high-tech company in the sense of producing high-tech products (aside from Kindle). It’s just a retailer that uses high-tech devices created by others. It started off selling just books and now sells over 200 million items in 35 departments.

At Barnes & Noble bookstores, average revenue per employee is $155,000. At Sears, it’s $140,000. At Amazon, it’s $491,000. This is exactly the sort of shakeup that corporate Japan needs. Unfortunately, in Japan, gazelles like Rakuten and Uniqlo are the exception, not the norm. Of course, at some point, even the most successful gazelle becomes an elephant. Economies need a constant infusion of new gazelles.

While Amazon is a huge household name, most gazelles remain anonymous and small. In 1993, the average American gazelle employed 61 people, but the 350,000 gazelles employed a total of 20 million people--a quarter of all American private firm employees (i.e., not counting the self-employed).

True gazelles are rare creatures. Even though the US regularly creates more than a half million new employer firms each year, only 5-10% of all new entrants are likely to become gazelles, according to Robert Litan, vice president of Research and Policy at the Kaufman Foundation. Most are either mice or failures.

Most would-be gazelles don’t survive. In the US, only half of all new establishments survive five years and just a third survive 10 years. But many of those that do survive can thrive. It is as if the economy were experimenting. It creates lots of new firms with different ideas of what innovations will work, the economic equivalent of the natural selection process in nature. The successful ones create competitive pressures compelling incumbent firms to change. Since most would-be gazelles fail, a country has to generate a lot of attempts to have sufficient success stories.

Birth and death of firms

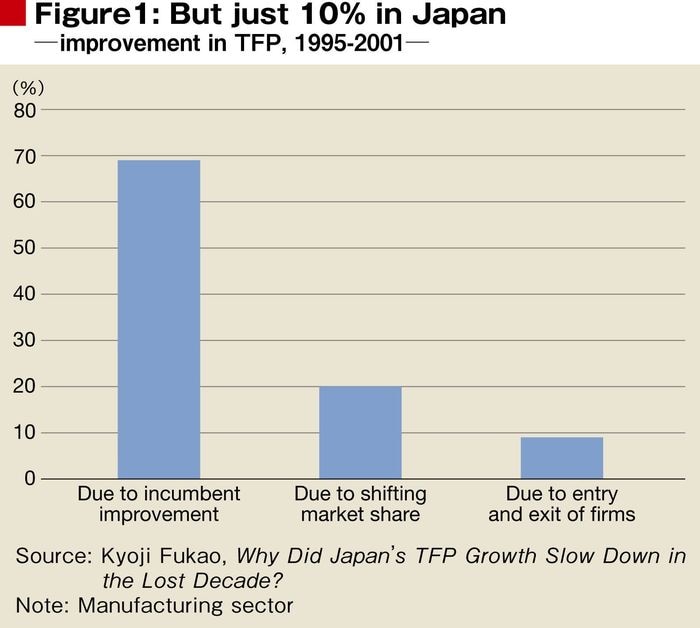

The key role of gazelles is to replace inferior firms with superior ones. Firms produce productivity in three different ways:

1) Existing firms improve their own efficiency;

2) The market share shifts from low-productivity incumbent firms to higher productivity existing firms;

3) Firm turnover, i.e., new higher-productivity firms arise and force older, lower-productivity companies out of the market.

An OECD study looked at this pattern among ten industrialized countries (not including Japan). It turns out that, on average, 40% of growth in Total Factor Productivity (TFP)--i.e., the productivity of labor and capital combined--results from new superior firms displacing older inferior ones. Another 13% stems from more efficient firms taking away market share from less efficient firms.

In Japan, by contrast, only 10% of TFP growth in manufacturing comes from the birth and death of firms (see Figure 1). That is one of the pivotal causes for the slowdown in Japan’s economic growth during the “lost decade” of the past quarter-century.

Why is the role of new firms so important? One reason, says the OECD, is that: “New technologies are often embodied in new capital, which, however, requires a retooling or remodeling process in existing plants...as well as changing work practices in some cases.

Insofar as new firms do not have to go through this process, they may better harness new technologies and growth will then tend to be associated with new entrants who displace obsolescent establishments.” By contrast, mature firms with “sunk costs” in older technologies may be reluctant to invest in technologies that are not only costly but also may accelerate the obsolescence of their existing products. Think of Sony’s reluctance to shed TVs.

Japan lacks natural selection

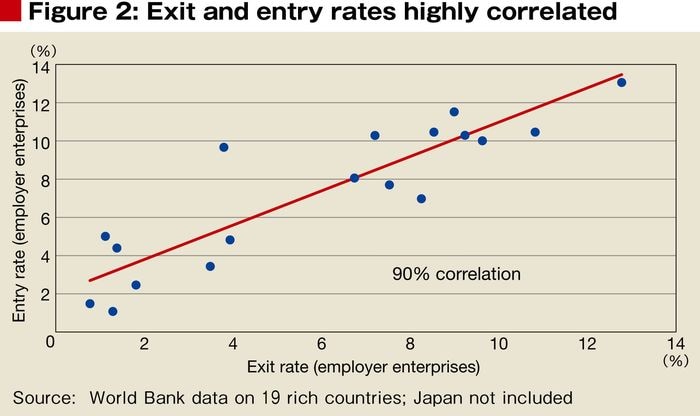

Creative destruction requires that some firms lose jobs and resources so that the latter may be transferred to new, more innovative firms. A country cannot have a high rate of new firms entering the business world if it protects older, inferior firms in the name of job preservation. Across a group of 19 rich countries, there is a very high 90% correlation between the rate of firm exit and of new firm entry (see Figure 2).

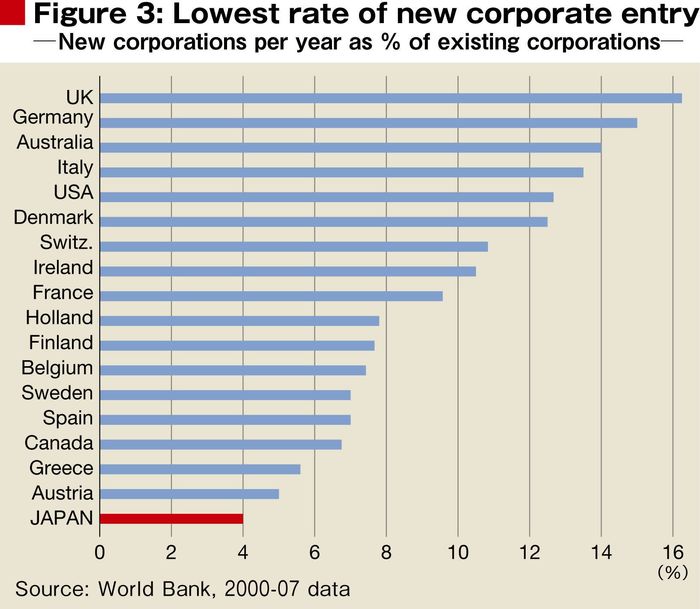

So, it is not surprising that Japan, which has, by far, the lowest rate among rich countries of firms exiting the market also has the lowest rate of new firms entering. Both stand at about 4%. The rate in Germany is double that. In France, it’s almost triple.

Different sources offer somewhat different results, but they’re all in the same ballpark.

The widely-cited Global Entrepreneurship Monitor (GEM) puts Japan as the lowest ranking country in a group of 23, with an entry rate of just 3.8% (see Figure 3).

We should note that these figures refer to all startups, not just would-be gazelles. Many of them are mice.

Japan is famous for having lots of Small and Medium Enterprises (SMEs). Only about 15% of Japanese work in firms with at least 250 workers, the lowest share among a couple dozen countries surveyed. But the real problem for Japan is that its SMEs are old. This is a problem because most potential “gazelles” are less than five years old. 75% of Japan’s SMEs are more than 10 years old. Only 5% are under two years old and about 12% less than five years old. In France, by contrast, only 40% are more than 10 years old, 20% are less than two years old and 40% less than five years old.

GEM reports: The average entrepreneur in Japan is over 45 years of age, male, and has a bachelor’s degree. He starts up his business in the industry where he worked before.

Far fewer of Japan’s startups become large firms. Take a look at Figure 5. Japan’s startups begin life somewhat smaller than those in most other rich countries, but not markedly so. For example, the average Japanese manufacturing firm under two years old has about five employees, versus ten in the US. The real difference is how big these firms (or establishments in the case of Japan) are after ten years.

In the US, the average manufacturing firm has grown eightfold, from ten employees to 80. In Britain, it has grown more than four times, from about eight to about 38. In Japan, the establishment has just doubled from five employees to about ten. The contrast is even greater in service firms, where Japanese establishments barely grow at all, in contrast to the big growth seen in service firms elsewhere.

And yet...

Using a database of 33,000 independent corporations founded during 1998-2008, scholars Robert Eberhart and Michael Gucwa created a profile of Japan’s startups. Contrary to most other studies, Eberhart and Gucwa find a lot of gazelles in the Japanese economy.

They argue that after the reforms that began in the late 1990s, new firms now grow to average industry size in just two or three years. Moreover, after five years or so, the sales of new corporations were, on average, at the 70th percentile of sales in their industry. In a random distribution, one would expect them eventually to grow to the 50th percentile. So, this data implies that many growing start-ups are superior to incumbent firms and that there are growth opportunities for them. The problem is too few attempts.

However, given the inordinate market share of the very largest firms--e.g., the top ten firms in agricultural chemicals control 85% of industry sales--the market share of a firm at the 70th percentile may still be tiny. Eberhart and Mucwa’s data shows that, among nearly 1,000 new high-tech corporations created between 2004 and 2008, only two had sales over $100 million in 2008. 55% had sales between $100,000 and $1 million.