The following article is based on the online series, "Jissen! Tsutawaru Eigo Training" by Katsuyoshi Hakoda (Instructor and Coordinator of English Language Education, AEON). Click here to read the original article in Japanese.

For the first time in 124 years, the Setsubun (節分) tradition of throwing beans and yelling “Demons out! Good fortune in!” occurred not on February 3 – when Setsubun is normally celebrated – but on February 2.

Hakoda-sensei blends astronomy and etymology as he describes why different dates are allocated to Setsubun and other seasonal holidays. In the process, he also sheds some light on “Nijyūshi (24) Sekki”, the ancient Japanese calendar which divides the year into 24 mini-seasons.

Nishi-Nibun (二至二分)

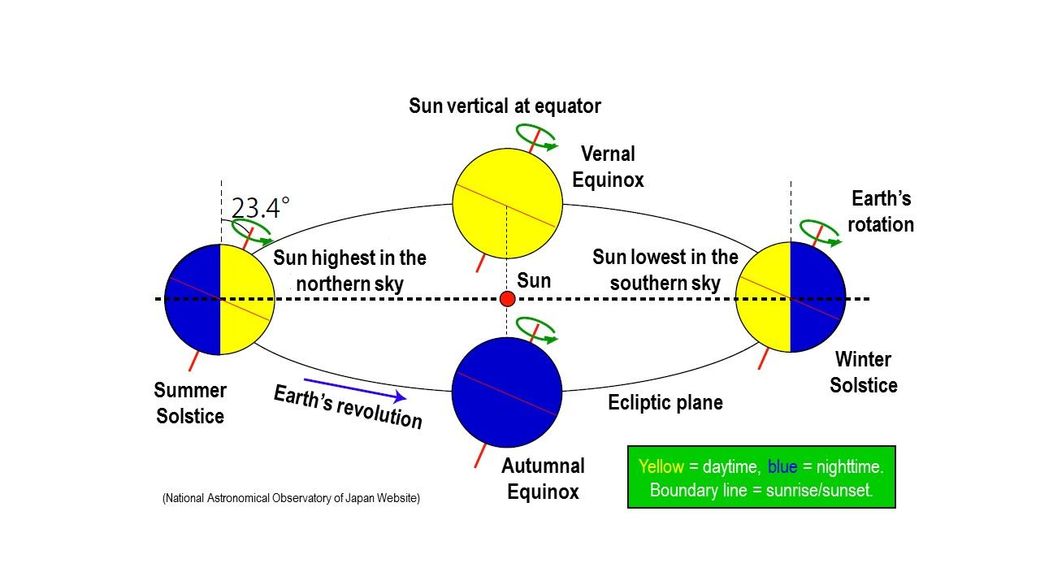

To start, we must recognize that the seasons are based off of the Earth’s orbit around the sun, with the equinoxes marking the days when the Sun is exactly above the equator. This results in a near-equal length of daylight and darkness. The solstices are when the Sun reaches its greatest distance from the equator, resulting in either the longest or shortest day of the year. These four cross-quarter days are known in Japan as Nishi-Nibun (二至二分) and means quite literally, “the two solstices (至) and the two equinoxes (分)”.

vernal equinox 春分 (Shunbun)

summer solstice 夏至 (Geshi)

autumnal equinox 秋分 (Shūbun)

winter solstice 冬至 (Tōji)

In English, the two solstices maintain their seasonal names (summer & winter), whereas the equinoxes use the adjective “vernal” and “autumnal”. Although not as common, equivalent season adjectives exist for summer and winter too.

vernal

estival (or aestival)

autumnal

hibernal (or brumal)

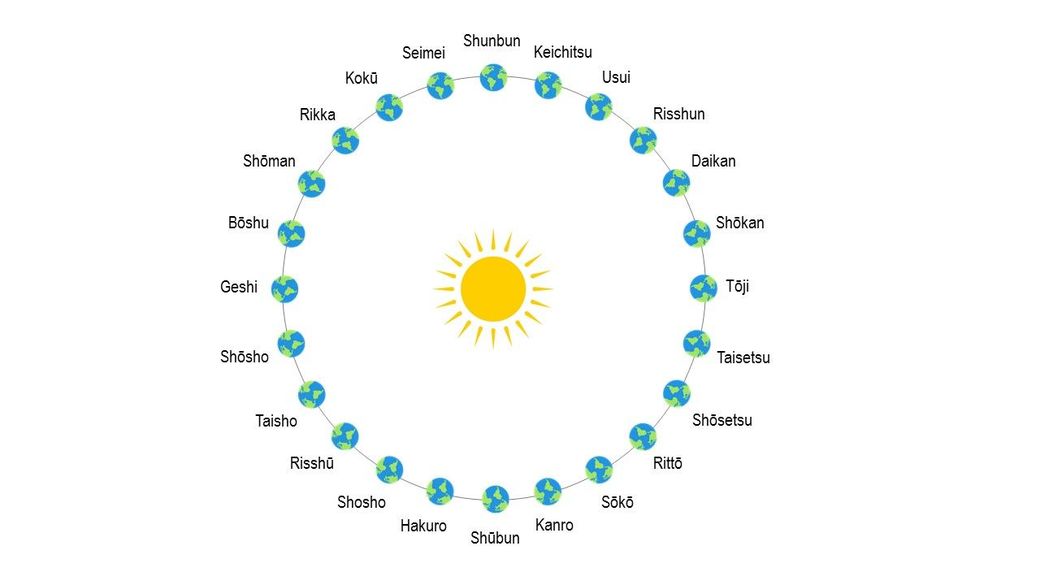

The movement of the Earth on the orbital plane is what decides Nishi-Nibun. The following diagram can be found on the website for the National Astronomical Observatory of Japan.

“Revolution” (公転) and “rotation” (自転) both represent circular movements. One rotates on an external axis whereas the other uses an internal axis. In simpler terms, revolution means “to orbit” and rotation means “to spin”.

Earth’s Orbit is Longer Than a Year?

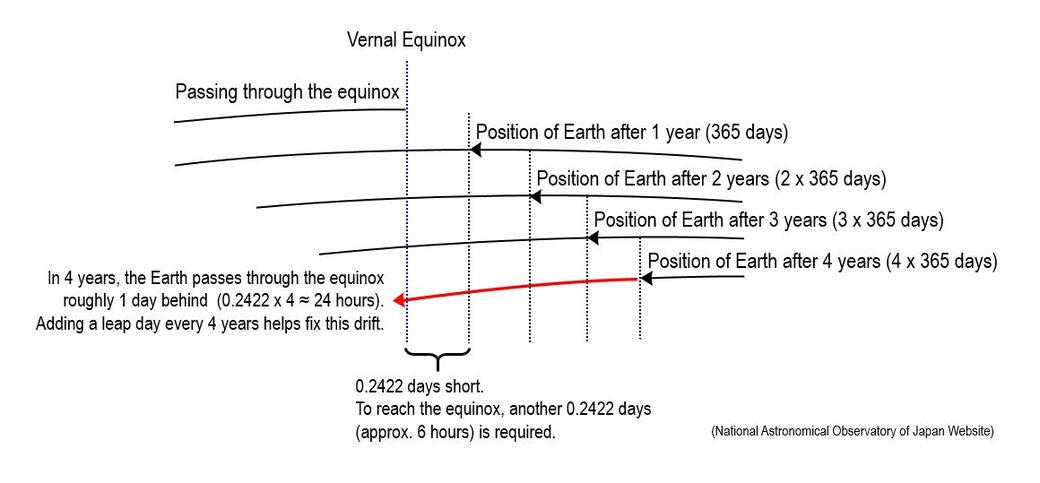

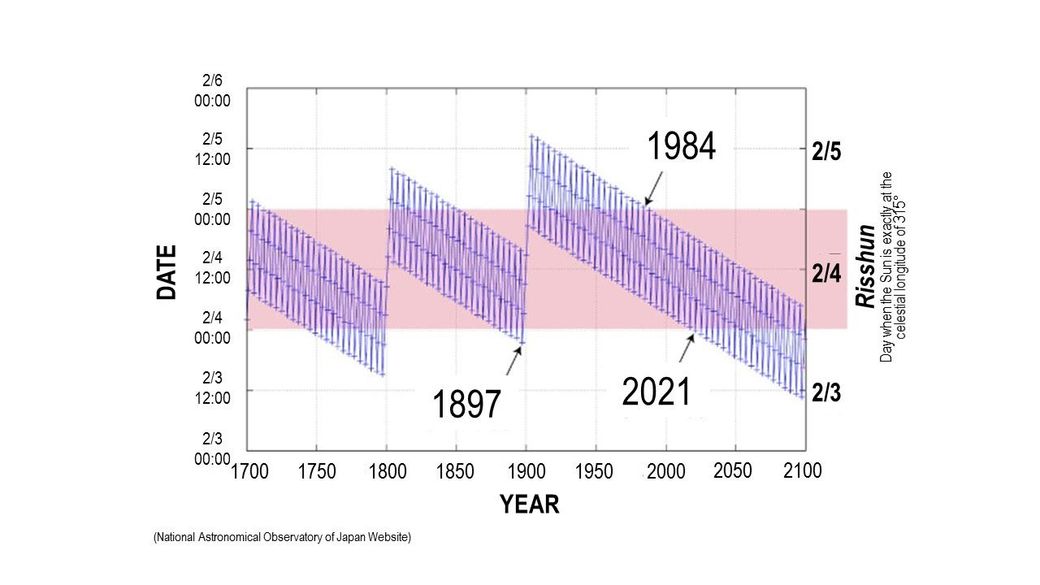

The calendar year consists of 365 days, but it actually takes slightly longer than that for the Earth to return to the same exact position – 365.242189 days to be exact. This is known as a “tropical year” or “solar year”. While one year has elapsed in the calendar year, the earth has not fully completed its revolution around the sun. Take a look at this chart, also brought to you by the National Astronomical Observatory of Japan website.

As the figure shows, the calendar year is slightly shorter than the actual time it takes for the earth to revolve around the sun, leading to an incremental drift. This 0.242189 days lost in a year is equivalent to approximately 6 hours. When we multiply this over 4 years, we end up drifting apart by nearly an entire day (6 hours x 4 years = 24 hours).

The leap year is designed to offset this deviation. Without the presence of leap years, summers and winters would be flipped in around 700 years. For those of us that dwell in the Northern Hemisphere, we’d be celebrating the New Year in a T-shirt. That might be interesting!

Leap years are supposed to help fix this issue. But if this were completely true, then why did Setsubun occur one day earlier? It goes back to the once-in-124-years event mentioned at the start.

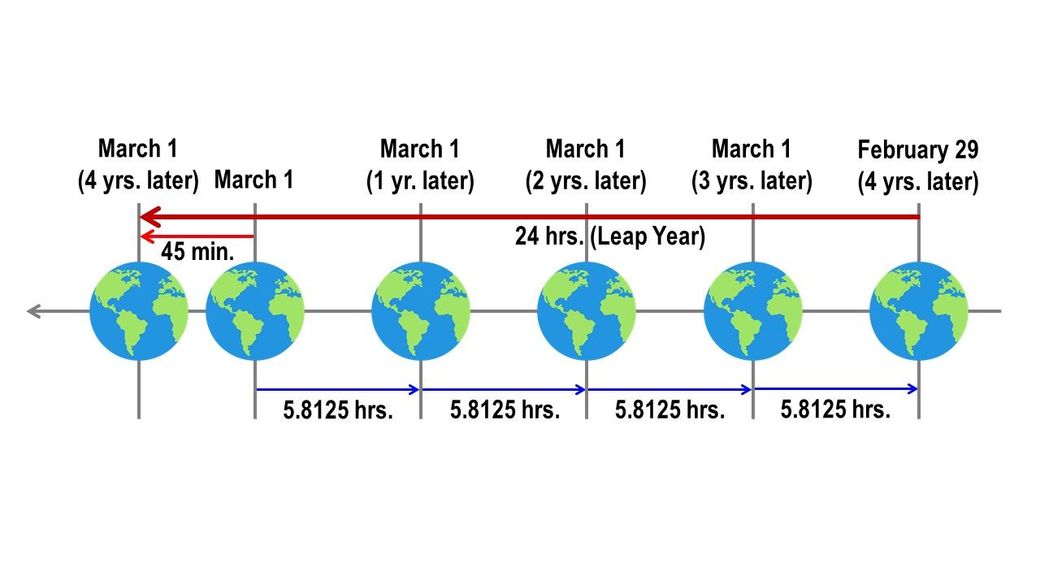

Resetting the Reset

We can crack this mystery by looking at the exact calculations. It was mentioned earlier that the days lost due to the drift was 0.242189 days, which is approximately 6 hours. To be more exact, it takes the Earth an additional 5 hours, 48 minutes and 45 seconds for it to revolve completely around the sun. So to reach this 6-hour mark, we must account for an extra 11.25 minutes. And even with the implementation of a leap year, we’ve created an orbital deficit of 45 minutes (11.25 x 4) over four years. Hakoda-sensei illustrates this phenomena using the following chart:

There is a 45-minute “slippage” that occurs every four years. In 400 years’ time, this is multiplied by 100, so we end up with a deviation of 4,500 minutes (75 hours) or 3.125 days.

By forgoing the leap year on the 100th year, 200th year and 300th year, we can cut down the deviation to only 0.125 days. The National Astronomical Observatory of Japan words this in the following way:

“A year that is evenly divisible by four is a leap year. However, years that are evenly divisible by 100 are common years unless they are also evenly divisible by 400.”

In other words, a leap year comes every four years, but in order to rectify the small drift that builds up over time, leap years must also be omitted three times over a 400-year period. The follow chart attempts to illustrate this complicated set of rules:

“Risshun” (立春) is the name used in the old Japanese calendar to mark the beginning of spring. In the years 2021 to 2100, Risshun will fall on February 3 for every year following a leap year (as illustrated in the chart above). “Setsubun” generally refers to the day before the first day of spring (Risshun). Thus, every four years from now until 2100, Setsubun will occur on February 2.

“Shunbun” (春分; Vernal Equinox Day) is traditionally celebrated on March 20. In the same way that a reset is needed for Risshun, in the year 2092, Shunbun will also be shifting to March 19. Be sure to mark your calendars for that!

The 24 Mini-Seasons of Japan

In addition to Nishi-Nibun, there is Shiryū (四立), the first day of each season. These are: Risshun (立春; beginning of spring), Rikka (立夏; beginning of summer), Risshū (立秋; beginning of autumn), and Rittō (立冬; beginning of winter). Shiryū is followed by five other “occasions” which together make up the “Nijyūshi (24) Sekki” (二十四節気), the division of the solar year into 24 equal sections. Hakoda-sensei charts their names (i.e. “Solar Terms”) relative to their position on earth’s orbit.

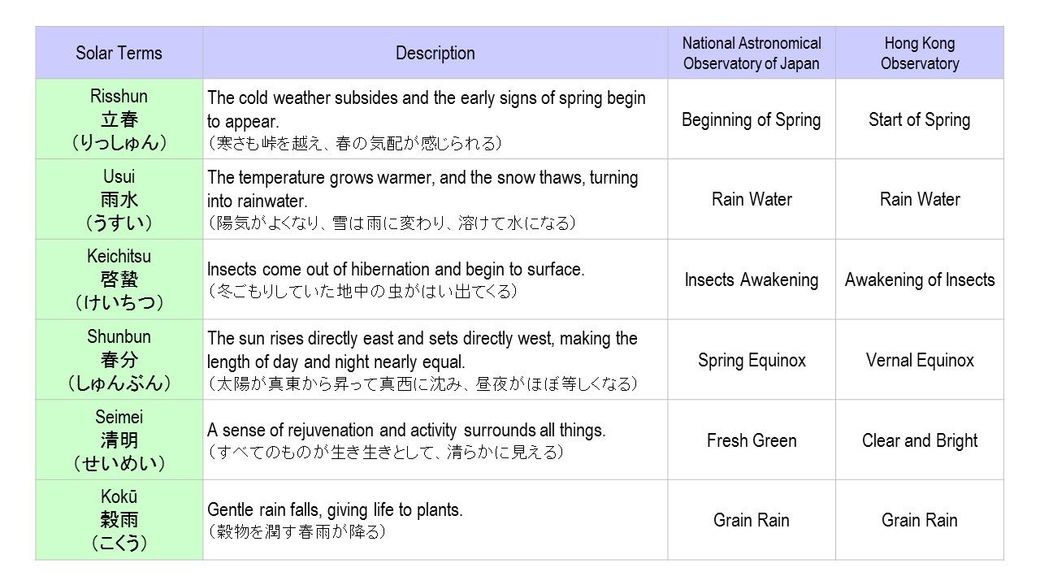

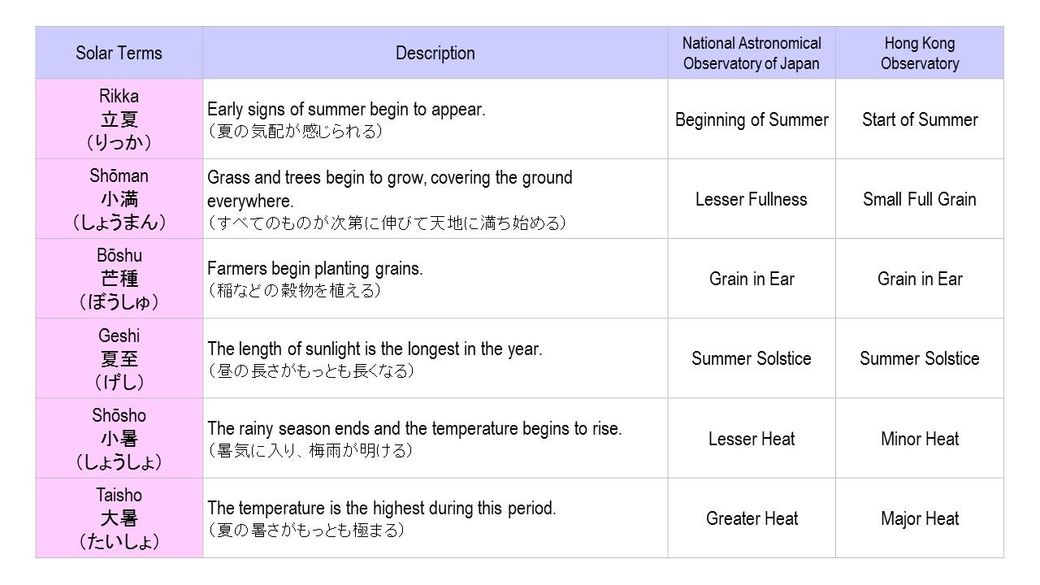

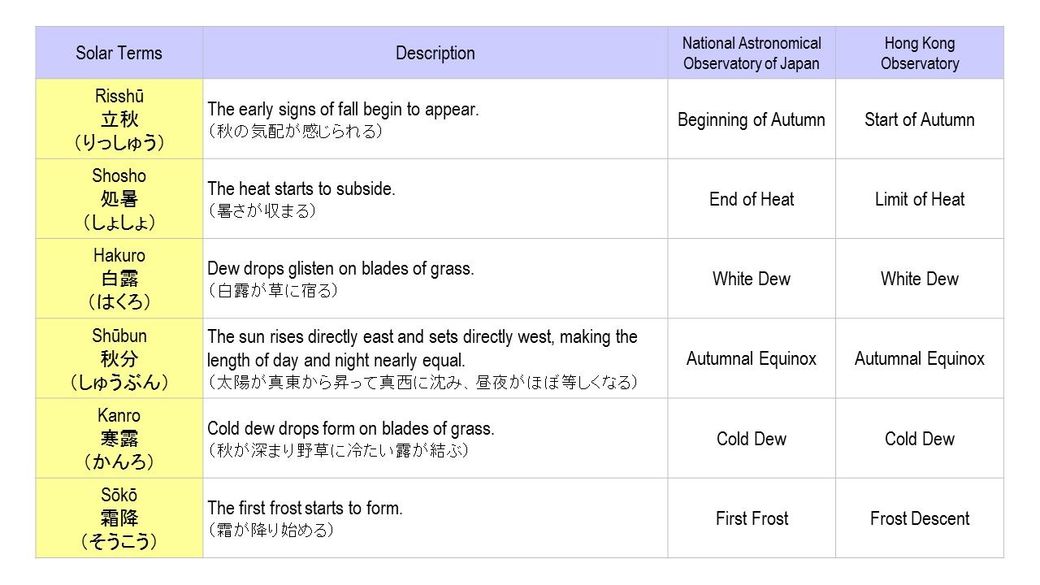

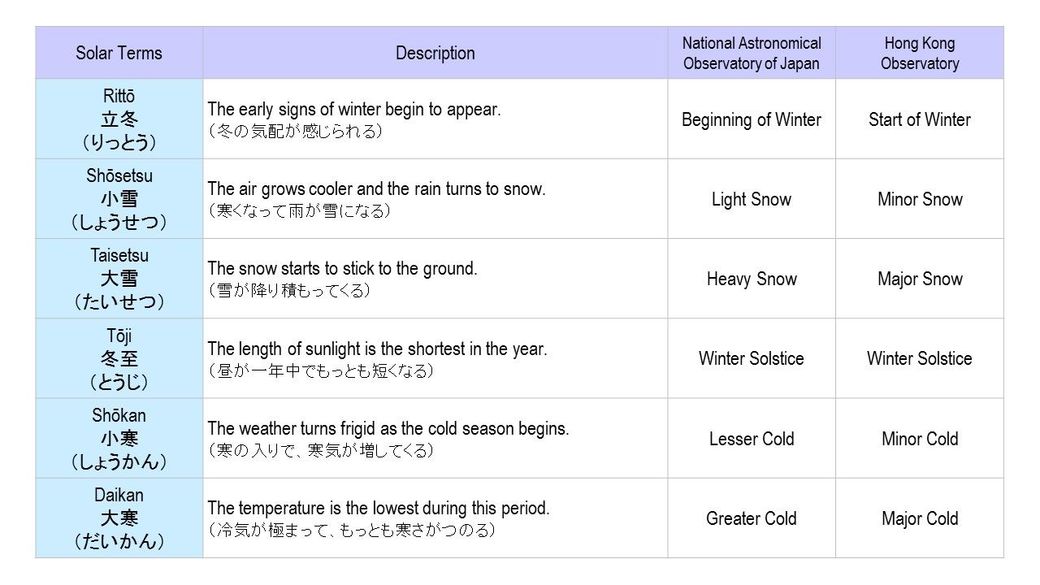

Although there don’t seem to be definitive English names for these 24 solar terms, the National Astronomical Observatory of Japan offers their English version of the names along with descriptions for each. For reference, Hakoda-sensei has also lined up the solar terms with the ones found on the Hong Kong Observatory website.

Origins of Nishi-Nibun

The descriptions above for the vernal and autumnal equinoxes (Shunbun & Shūbun) state: “the length of day and night becomes nearly equal”. “Equinox” descends from the Latin word “aequus” meaning “equal”, and “nox” meaning “night”. This is a fitting name for the two days where daytime and nighttime become equal in length.

But why “nearly equal” and not exact? The first reason has to do with the way we measure sunrises and sunsets. Daytime begins the moment the upper edge of the sun appears over the eastern horizon and ends once the upper edge sinks below the western horizon. When factoring in the distance between the center of the sun and its upper/lower edges, we end up with a slightly longer day than night.

Another reason has to do with the Earth’s atmosphere which refracts the light from the rising sun and bends it toward our sightline a few minutes before its upper edge reaches the horizon. The same effect occurs right after the sun dips below the horizon, adding even more daylight during the equinox. So remember, day and night are NOT equal at the equinoxes!

“Solstices” comes from the Latin word “sol” meaning “the sun” and “stitium” based on the word “sistere” meaning “to stand still”. The two solstices are often described as “the point at which the sun seems to stand still”. This may be especially relevant to the summer solstice (Geshi), where the sun seems to sit still in the sky for an extended period of time.

Learning all 24 solar terms may seem daunting at first, so Hakoda-sensei suggests starting with Nishi-Nibun and slowly working your way through the rest. If nothing else, take the time to appreciate the subtle changing of the 24 mini-seasons as described in the ancient Japanese calendar of Nijyūshi Sekki.