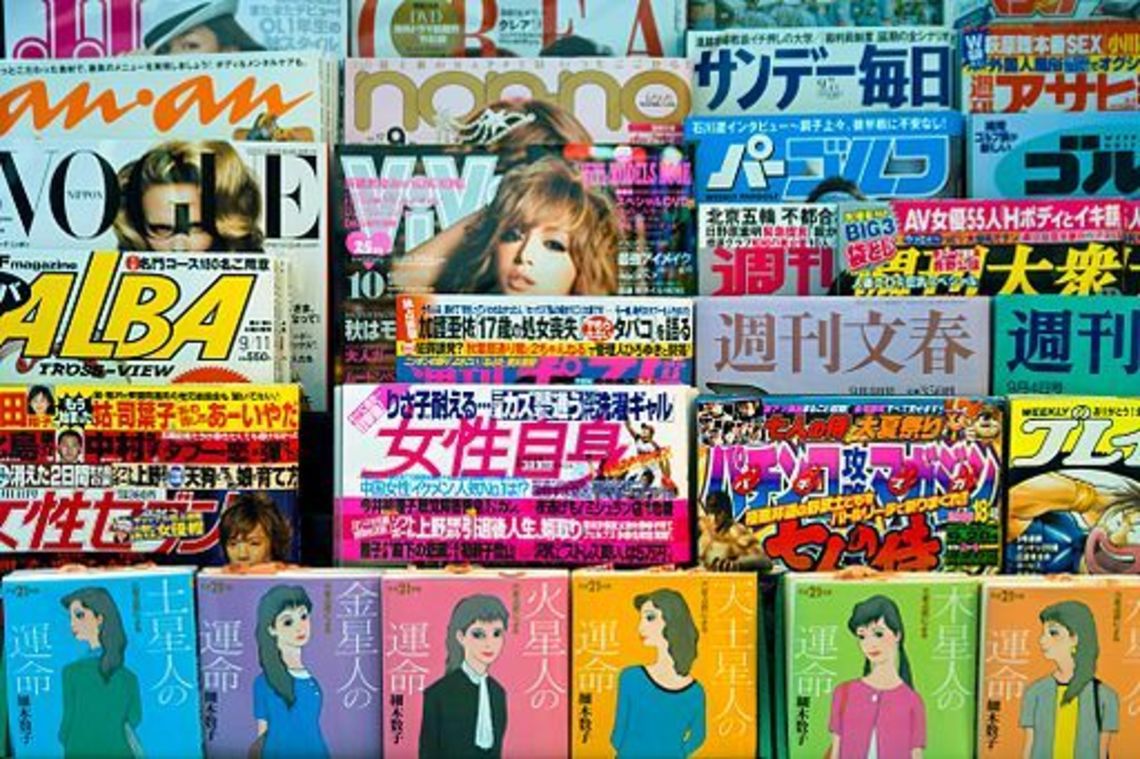

9.1 million… 6.8 million… 2.7 million. These are the circulation numbers for the Yomiuri Shimbun, the Asahi Shimbun, and Nikkei Shimbun respectively – three of Japan’s biggest morning newspapers and some of its most influential news sources. While many countries are fully embracing the digital revolution, Japan could be described as a paradise for the printing press.

Nevertheless, industry savvy experts foresee a crisis approaching within the traditional media scene for which many Japanese businesses are neither aware nor prepared for due to top-down management and a reliance on traditional media publicity. Newspapers are slowly but steadily losing readers, especially among younger demographics.

Candid conversations with chief editors of magazines reveal some disturbing trends for the industry: print publications are no longer attracting the number of new readers they need to maintain their previous levels of financial viability as yields from advertising are quickly falling. TV, while still arguably in the best position among traditional Japanese media outlets, now has to compete with plummeting attention spans, rising levels of online video consumption, and appealing video streaming services.

Businesses and marketing professionals in Japan have typically placed far more importance on traditional media, often neglecting online distribution. However, this needs to change as the shift to greater digital media consumption continues.

With many Japanese youth now glued to the screen of their smartphones, the newspapers and weekly tabloids that distracted young commuters in the past have all but been abandoned by today’s digital generation. As might be expected, many young people are now getting their media fix via SNS and other sites that cater to specific niche interests.

It’s becoming harder and harder to find anyone under 35 who regularly reads print media. Ask a group of 20 year olds when the last time they looked at a newspaper and most will simply shake their heads. A large number of Japanese people have thoroughly integrated the smartphone into their daily lives and made the shift to mobile for ALL of their media needs.

Prepare for the change

Companies and media professionals who don’t adapt and prepare for the changes taking place will eventually be rendered obsolete since more and more people are opting to consume their media online. Brands seeking the attention of new Japanese customers can no longer afford to ignore online media channels.

In order to break through the noise and reach the younger generations of Japanese society, brands operating in Japan will need to become masters of the following, in a specifically Japanese way, in order to succeed:

• Great Storytelling: While top PR and marketing professionals have always been marked by their ability to tell stories, understanding how to localize and then convey a brand’s identity online for the Japanese consumer will be crucial. Online, every story is consumed à la carte, meaning that it is vital to wrap messages in easy, but fun to consume, narratives that are sharable.

• Adaptability: While with a platform like television, viewers have little choice but to watch a commercial or change the channel, these interruptions can often be ignored entirely online by potential consumers. To succeed online, a piece of content must appear to be native to the medium in which it appears. Professionals looking to promote brands successfully online will have to respect each and every platform’s individual quirks.

Adaptability should be emphasized in Japan as the in-group out-group culture plays a large role in influencing decisions. A brand’s ability to carefully curate content for different groups will have a large effect on results.

• Brevity: The average landing page has only a few seconds to grab the attention of a potential viewer and the outlook is even grimmer on social media. To succeed in such a competitive environment, it is necessary to be able to distill the essence of a story into small, bite-sized chunks that can be consumed in the few seconds of micro leisure that smartphone users take throughout the day.

Brevity leaves a lot more room for creativity in Japan, as more can be said with one character through Kanji than it can be in English. For example, it is possible to pack a full mini-story within the character limit in Japanese on Twitter.

• Virulence: Unlike with subscription models where readers pay up front monthly, stories online are consumed in a one-off manner. With each bit of content fighting for attention, what doesn’t spread is functionally dead. It is critical that virality be built into the story from the outset if it is to be effective. One point of warning in Japan is that Japanese people are much less outspoken and unlikely to react or share “negative” content. Cute and funny content has a much higher chance of going viral and resonating with Japanese audiences.

Why has Japan been late to join the digital revolution?

However, in order to fully understand the changing Japanese media landscape, we must first understand the past. There are a number of key questions that need answers: How has print media been able to hang on like it has in Japan? What do iPhones and Androids have to do with the coming shift to digital media? If print media is indeed declining at a steady rate, how can it be possible that Japan is facing a so-called print media crisis when circulation numbers are many times higher than their overseas counterparts?

Answering these questions first require us to reflect on the state of the Japanese Internet over the past 20 years. There are several reasons why the country has been late to join the digital revolution and why the next few years will drastically alter the media landscape.

Unlike in the U.S. and the U.K., most Japanese people have grown up without ever really learning how to use a computer. Proper usage is rarely, if ever, taught in high schools and there are few educational resources to help.

Furthermore, most Japanese youth do not spend a significant amount of time at home each day due to long commutes and extra-curricular activities. Even people who, by choice or circumstances, were fortunate enough to have access to a personal computer never developed the same level of familiarity that those in the US and Europe have come to expect.

Japan is a curious market because, although economically able, many of its citizens still struggle with basic computing tasks. Unlike the digital natives of other countries, who grew up spending hours upon hours in virtual worlds such as World of Warcraft, networking on early incarnations of Facebook and Myspace, or illegally downloading music via torrents, their Japanese counterparts were mastering a different style of web designed for Japan’s advanced flip phone and data infrastructure.

It wasn’t until the arrival of the smartphone in Japan that the online experiences familiar to the rest of the world started to be adopted. Since the advent of iPhones and Androids, everyone carrying a smartphone has had access to a brand new Internet experience never possible on common feature flip phones. There are many teenagers who have only ever truly experienced the Internet through their smartphone, giving rise to new platforms that have emerged to cater to these audiences (such as the mobile blogging site Ameblo).

Historically, magazines have operated on the premise of targeting very specific niche demographics. For example, Shogakukan’s female magazine CanCam (circulation: 140,000) traditionally targeted university aged girls and produced content relevant to their life needs. Readers would be avid fans of the publication during their tenure in university, and afterwards, they would “graduate” to the next publication.

Widespread, mobile Internet access has disrupted this media conveyor belt, and now, instead of graduating to the next publication, many readers are moving to online media. Realizing this new trend, magazines are now “maturing” with their readers in an attempt to hold on to their current audiences.

Gainer, a magazine for men, has a similar story. It originally targeted readers in their late 30s who still maintained their zest for life. Now, however, the magazine has found that to keep readership at sustainable levels, they have had to adjust their content in-step with their readers’ age. There is an interesting parallel here with Japanese manga like One Piece and Dragonball, in which the maturity of the narrative “grew up” with their reader base.

Nevertheless, legacy media is still holding on because those with purchasing power in Japan tend to be older, and the country is rapidly aging. In fact, according to Nikkei Business, seniors are currently leading the leisure market since they have both the time and the means to enjoy it (unlike their overworked younger counterparts).

It’s also significant to note that Japanese society is culturally structured to determine influence based on age and position. This is a key reason why traditional media continue to be so influential and trusted and make up the lion’s share of new trends. The newest stories and trends typically originate on print or TV, flowing to online media after their original debut. This is why it is important to also focus on traditional coverage whenever possible.

But, as more of Japan’s post-war generation retires, the countdown continues. Dropping circulation numbers are a big reason why many influential media are adopting online versions of their own columns and news.

For the immediate future, brands in Japan may be able to continue to hang on by seeking exposure in traditional media to reach older customers who still consume print. However, as younger consumers begin to enter their prime spending years, brands seeking to promote their products and services in Japan will need to consider new approaches more in line with the rapidly changing times in order to get their messages out and survive.