Personality counts for a lot in politics, at least for a while. It’s giving Sanae Takaichi a big honeymoon in her initial approval ratings. Yet, personality cannot overcome the fact that the Liberal Democratic Party (LDP) is out of touch with voter needs and opinions.

I was struck by the LDP’s blindness in January when I asked an LDP leader: “What message were the voters sending when they denied the LDP a majority in the Lower House?” He smugly replied: “There was no message. Voters were just upset about the campaign finance scandals, and that will soon wear off. We’ll win the coming Upper House election.”

The LDP’s right wing is still in denial, insisting the party lost its majority because of Shigeru Ishiba. On the contrary, in an Asahi poll 81% said the LDP lost due to problems with the party as a whole. Takaichi also tells herself that voters recall Abenomics with fondness. In reality, a Jiji Press poll in 2021 found that only 15% wanted Kishida to continue Abenomics.

The Unreality of Sanaenomics

Even though 73% of voters wanted the government’s top priority to be countering inflation, and even though prices have outrun wages in six of the last seven years, Takaichi was the only LDP Presidential candidate who refused to offer any plan to bring down inflation or to raise real wages. On the contrary, Takaichi warned the Bank of Japan (BOJ) that it would be “premature to relax our guard [and raise interest rates—RK] by concluding that deflation has ended.” Moreover, she supports a weak yen despite its pivotal role in raising food and energy prices.

She refused to have a wage plan, arguing that this is “something private companies decide.” Unlike her predecessors, including Shinzo Abe, she offered no target for a minimum-wage hike.

She has ruled out any cut in the consumption tax, even a temporary one for food. Yet tax-cut proposals by opposition parties were a key reason they beat the LDP in the past two elections. She did, however, pledge in her policy speech to the Diet to raise the zero income tax bracket from ¥1.03 to ¥1.6 million. It remains to be seen if she will actually push this through the Diet.

Although some commentators call Takaichi a serious policy wonk, even a brilliant one, to me, she seems lost in a world of unreality reminiscent of Donald Trump. She spouts myths that justify serving the needs of assorted vested interests. Consider her stance on energy. She vows to make Japan 100% self-sufficient in energy to ensure security. Yet she supports the continued use of coal- and natural gas-fired power plants. Where does she think the coal and natural gas come from?

She supports hybrids against electric vehicles and intends to reduce subsidies for the latter, ignoring that gasoline requires oil imports. She plans to cut aid to solar power, exclaiming that she opposes “further covering our beautiful land with foreign-made solar panels.” She wants more nuclear energy, even though reactors need uranium imports every 18 to 24 months. And then there is the biggest fantasy of all: that fusion power will be commercially viable by the 2030s. Despite great progress, most experts don’t foresee fusion becoming a commercial reality for at least another 30 years.

As to why she supports a weak yen, it is likely connected to her declaration that “We will protect the automotive and related industries at all costs,” including, presumably, the cost of higher consumer prices.

Sanaenomics Vs. Abenomics on Monetary and Fiscal Policy

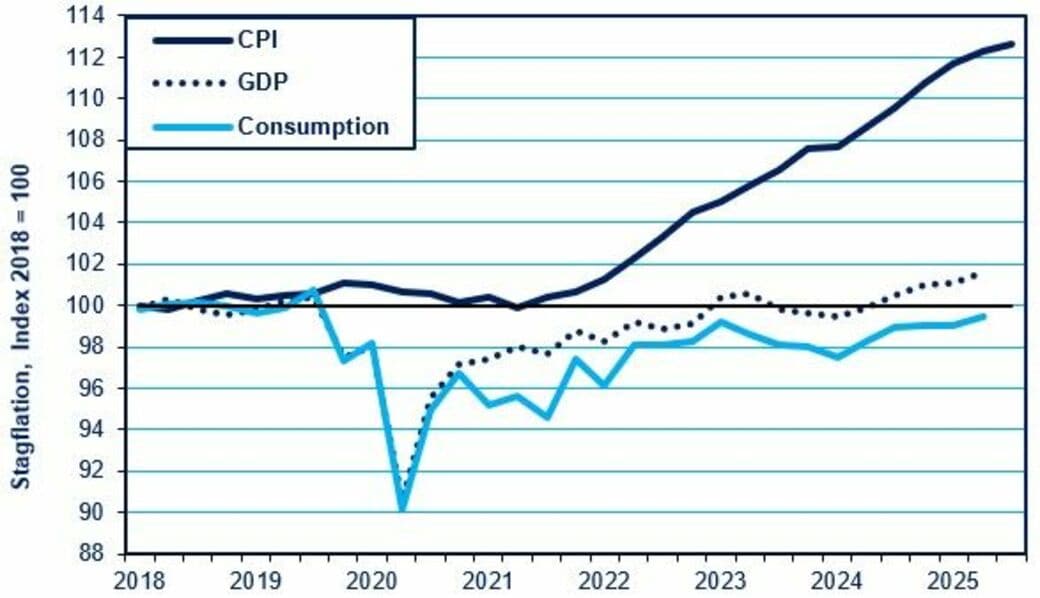

Takaichi brings a similar unreality to her campaign to resurrect Abenomics. Takaichi wants to fight the war of the prior decade —conquering deflation —with Abe’s first arrow of monetary stimulus. But the enemy these days is “stagflation”: stagnant consumer spending and GDP combined with inflation.

Stagflation creates a dilemma because addressing inflation with higher interest rates makes it harder to stimulate a flat economy with low interest rates. Shigeto Nagai, head of Japan analysis at Oxford Economics, commented. “Most understand that the original Abenomics wouldn’t work anymore.”

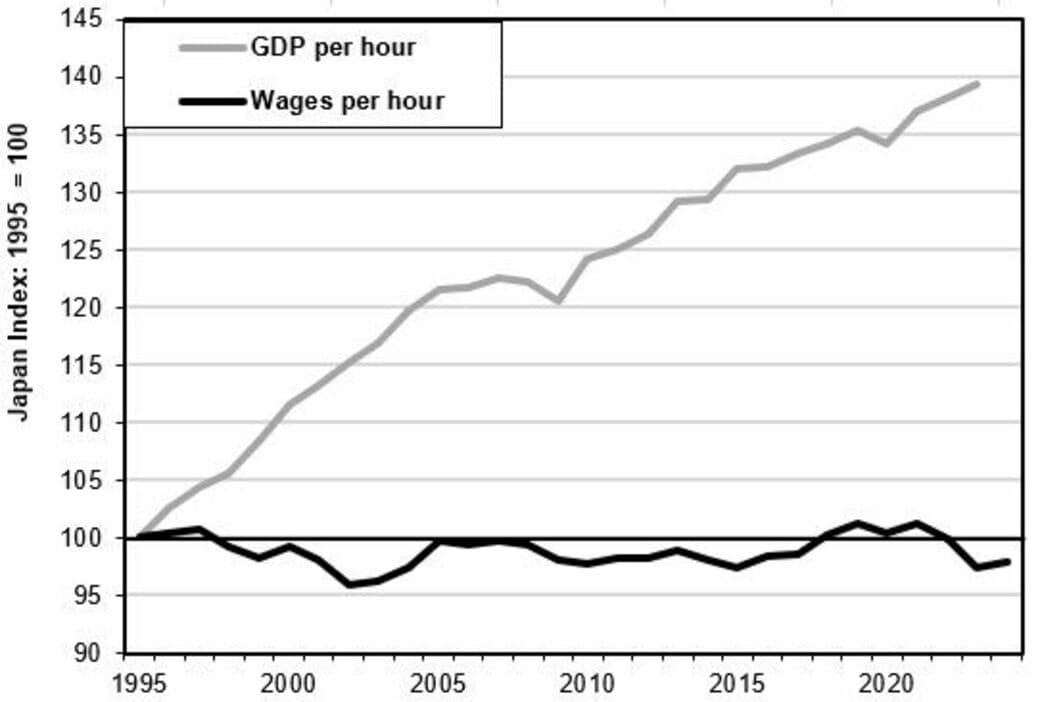

Similarly, Takaichi views Abe’s second arrow, fiscal stimulus, as a magic bullet, claiming that a “high-pressure economy” generated by heavy government spending would raise wages. Really? Why, then, has so much fiscal and monetary stimulus for so many years left real wages no higher than in 1995 despite growth in output per work hour?

Moreover, she champions a weak yen while denying that this is one of the primary causes of high prices. In fact, 80% of the price rise since 2021 has come from the import-intensive categories of food and energy.

Nonetheless, one of her chief advisors, Takuji Aida, chief economist at Credit Agricole, contends that a weak yen is good for the economy. “We've developed a defeatist mindset, thinking that a weaker yen is bad. That's a major mistake…At ¥140-150, it becomes viable to manufacture goods domestically. This exchange rate level is helping drive the capital investment cycle upward and also serves as a buffer against U.S. tariffs.” This is the failed Abenomics policy of driving the yen weaker in the hope that a resulting surge in exports will trickle down to more investment and higher wages. The yen has fallen to around ¥154 per dollar since she became Prime Minister.

Finally, Takaichi believes she can combine low interest rates with bigger budget deficits. In reality, larger deficits will exacerbate inflation and put pressure on the BOJ to raise interest rates.

Japan’s biggest problem is stagnant living standards. It will be hard for her approval ratings to stay so high if she not only fails to offer a solution but also sometimes claims that what people see as a problem —high prices —is not really a problem.

Takaichi’s Third Arrow Vs. Abe’s

In 2021, during her first run at the premiership, Takaichi outlined a revealing difference between herself and Shinzo Abe. Abe aimed his third arrow at a “growth strategy that brings out the vitality of the private sector.” By contrast, her bull’s eye is “bold crisis management investment and growth investment” in key technologies and industries. She wants the government to pour in money via public-private partnerships in each field.

Abe’s view was the correct one. If only he had done something beyond some corporate governance reforms. Japan’s industrial policy has been most successful when it accelerated market developments, as in autos and electronics during the high-growth era. By contrast, industrial policy repeatedly failed when the state tried to substitute for the private sector, e.g., the failed efforts in fifth-generation computers, uranium reprocessing, a fast-breeder reactor for nuclear power, and Takaichi’s personal poster child, the state-funded Rapidus. The latter’s goal is to leapfrog other countries by producing mass-market 2-nanometer semiconductors by 2027. The government is pouring upwards of ¥4 trillion into this effort. Experts doubt it will ever be profitable.

Her targets are widespread: artificial intelligence, semiconductors, perovskites [thin film for solar power], all-solid-state batteries, digital, quantum, nuclear fusion, materials, synthetic biology and biotechnology, aviation and space, shipbuilding, drug discovery, advanced medical care, transmission and distribution networks, port logistics, etc. But it goes beyond that to a semi-autarkic view that “To ensure all manufacturing industries can properly produce goods domestically is the absolute foundation of economic security.”

While Abe certainly engaged in vote-seeking protectionism and techno-nationalism in certain sectors, he was an internationalist when it came to economic and security policy, rather than issues of history. A prime example is the Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP). Yes, agricultural protectionism greatly delayed a timely agreement between Tokyo and the Obama administration. However, when Donald Trump abandoned TPP, Abe acted to make sure that the TPP survived. He also presided over an increase in foreign workers, something that Takaichi is backing down on—sometimes with Trumpian rhetoric about immigrants and tourists.

Takaichi Lacks Abe’s Clout

Shinzo Abe was king of his castle; Sanae Takaichi is not. A year ago, she said a temporary cut in the consumption tax was an idea worth considering. Since becoming Prime Minister, however, she has appointed fiscal hawks to top posts, including LDP baron Taro Aso as the new LDP Vice President and Shunichi Suzuki as LDP Secretary-General. Then, she ruled out a tax cut.

She has also walked back her talk of renegotiating parts of the tariff and investment pact Trump imposed on Ishiba. During a TV debate, Takaichi was the only candidate to say there were unequal elements in the pact. Having been reined in, she now says, “I will not overturn what Japan and the US have agreed upon.” She even appointed as the new METI Minister Ryosei Akazawa, who negotiated the unequal pact with Trump and became notorious for being photographed in a MAGA cap when talking to Trump.

But neither can the fiscal hawks easily impose their will. Japan runs budget deficits, not simply because politicians like to hand out goodies, but primarily because, with household income so flat, the government has to become the “buyer of last resort” to keep the economy afloat. Over the past decade, government spending accounted for half of all GDP growth.

On top of all this, Takaichi will have to compromise with the opposition parties on a myriad of issues, having reduced the LDP’s Diet minority to an even smaller minority.

Reality is creating difficult policy dilemmas. How Takaichi handles them will determine how long her honeymoon lasts.