Seeming to come out of nowhere—with 2021 global sales a mere 7% of Toyota’s—Chinese automaker BYD could in five years try to seize Toyota’s crown as the world’s top automaker. Last year, BYD leapfrogged past Hyundai, Ford, Honda, Nissan, and Suzuki to become the world’s fifth-largest automaker. This year, its sales will likely reach half of Toyota’s. If it reaches its 2026 goal of 6.5 million (a quarter of them in overseas markets), it will likely outdistance GM and Stellantis to rank third. What makes all this even more spectacular is that it only sells BEVs (battery-operated vehicles) and PHEVs (plug-in EVs).

BYD’s next step is challenging the leaders in their own strongholds. By 2030, it plans to sell around 5 million vehicles outside of China, half its global total, having already established overseas plants and building more.

BYD is not alone. Its compatriot, Geely (including its foreign subsidiaries), has also surpassed all the Japanese companies except Toyota and now ranks eighth. 40% of its sales are BEVs, PHEVs, and the like. It could pass Ford, and perhaps even Hyundai, within two years.

While the Chinese market share is rising, Japan’s is falling. Japan’s global share peaked in 2019 peak at a stunning 31.5%. As of 2024, the share had declined by four percentage points to 27.6%. Of the 17 biggest automakers, Honda ranked 9th, Suzuki 10th, Nissan 11th, while Mazda, Subaru, and Mitsubishi were the three lowest.

In China, Japanese sales have fallen for three years in a row. BEVs and PHEVs each comprise a quarter of all auto sales, and Japanese companies can’t supply enough of the product. Back in 2021, China accounted for a third of all global sales for each company. By 2024, their sales had halved. Although Toyota sales fell only 8% during this period, auto sales are growing so fast that Toyota’s share tumbled from 9% to 5.6%. Toyota missed a big growth opportunity.Mitsubishi abandoned China in 2023.

Nissan announced in late May that it would cut its global capacity further to just 2.5 million vehicles, less than half of its 2017 peak of six million.

Detroit Redux

Japanese automakers are losing customers because they are acting just like the Detroit Three acted in the 1970s in response to the Japanese challenge. Just as Detroit disbelieved the customer shift to gas-efficient and lower-defect cars back then, Toyota, Honda, et. al., are deceiving themselves about the BEV challenge. The International Energy Agency (IEA) expects BEVs and PHEVs to enjoy a combined global market share of 40% by 2030 and 55% by 2035 (80% of them being BEVs).

S&P has a higher forecast, with BEVs alone at 40% by 2030. Even in the US, despite Trump’s efforts, JD Power says BEVs will rise from a 9% share this year to 26% by 2030. An S&P report headlined the bottom line: “Slower EV Growth Offers Temporary Relief To Legacy Automakers.”

Because the Japanese companies are investing so much in hybrids as a panacea, they don’t want to believe how rapidly customer preferences are changing.

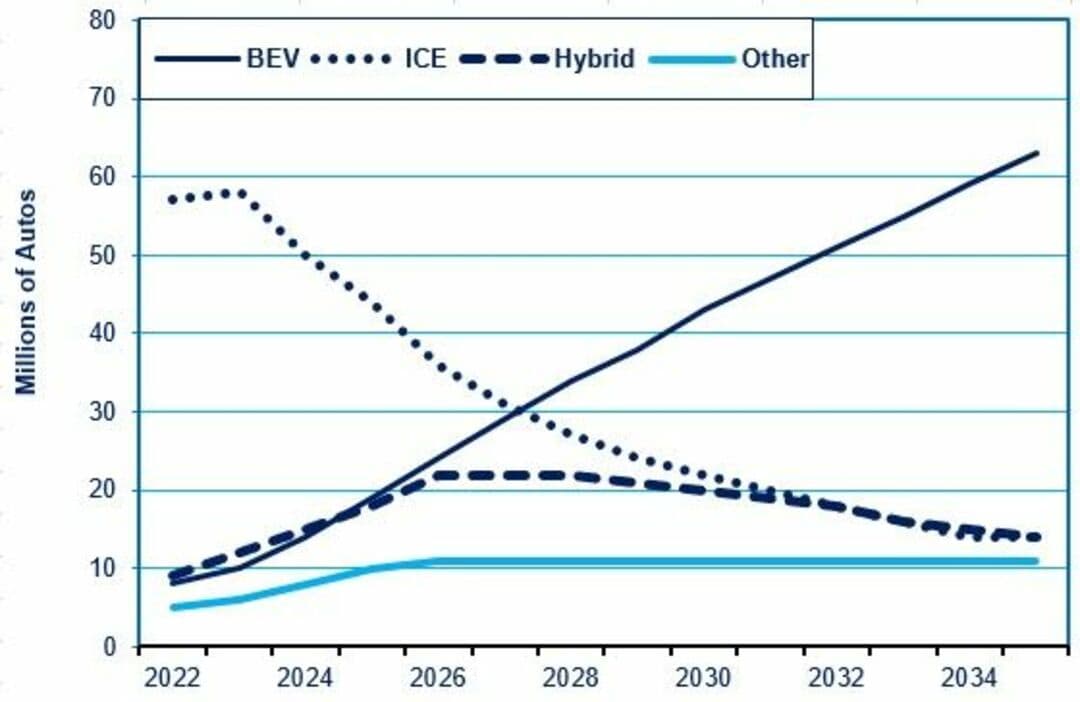

Global sales of gasoline-only Internal Combustion Engine (ICE) vehicles peaked in 2017 at 83.3 million units and, by 2024, had plunged to just 60 million. By 2030, ICEs could be down to somewhere between 20 and 25 million, according to S&P.

Conversely, BEV sales rose from a negligible amount in 2017 to 16% of the global market in the first quarter of this year. PHEVs accounted for another 6% while hybrids comprised 14.4%. For the whole year, the BEV share could rise to 18%.

Currently, in the major markets that PWC covers— 85% of the global market—BEVs and HEVs each accounted for 16% of the auto market and PHEVs another 8.4%, a fact that makes Toyota et. al. think they’ve judged the market correctly. However, says PWC, by 2030, customers worldwide will buy 30% more BEVs than HEVs. Worse yet, S&P forecasts that global hybrid sales (HEVs plus PHEVs) will peak at 22 million in 2028 and then fall to just 14 million by 2035. If S&P is right, the perceived future on which Toyota is basing its strategy won’t exist a decade from now.

Three obstacles must be overcome to transform BEVs from a luxury item to a product for the masses: high prices, range anxiety, and a long charging time. Rapid progress is being made on all three fronts, partly due to technological leaps and policy support.

Blind Spot

To virtually ignore models that will account for almost one out of every five vehicles this year—and perhaps one in three by 2030—seems rather foolhardy. Nonetheless, the Japanese automakers currently produce only about 2% of the global output of BEVs. They’re biased against BEVs and produce few PHEVs because they see them threatening a return on their investments in conventional hybrids (HEVs). That’s particularly true of Toyota, whose hybrids comprise almost half of their global sales, most of the rest being ICEs. At Honda, it’s practically an 80:20 ICE:HEV split with a negligible amount of BEVs. No wonder Honda’s global market share fell from 6.1% in 2019 to just 4.6% in 2024.

It's undeniable that Toyota’s HEV-focused strategy has earned it lots of sales and profits these days. That’s because it dominates in Japan, where hybrids comprise 61% of auto sales, and 15% of its sales come in the US, where hybrids now outsell BEVs. But if S&P is right about hybrid sales peaking out in a few years, the profits earned today come at the expense of tomorrow’s sales and profits.

While the Japanese players are increasing their sales of BEVs, they’re doing so at a snail’s pace. Of the top 23 BEV producers in the world in 2024, Honda came in 23rd at just 40,000 units, and Toyota was 20th at 140,000. Even with their pullback, other legacy firms are moving much faster. VW sold nearly 750,000; BMW 425,000; Hyundai 400,000; Renault 300,000; GM 235,000, and so forth.

Honda has already lowered its 2030 goal for BEVs from 30% of total output to 20%. That’s far below the expected global share of BEVs. And, who knows if Honda will achieve even that? Toyota still denies press reports that it lowered its goals for 1.5 million BEVs in 2026 and 3.5 million in 2030, or 30% of sales. If press reports that it plans only 1 million in 2027 are true, then it’s hard to see 3.5 million in 2030. Talk of a multi-pathway strategy may turn out to be just tatemae.

Toyota and the rest may believe that, if need be, they can rev up production and put out competitive BEVs whenever they want to. However, fabricating a BEV requires very different methods from making an ICE or HEV. When a product is new, companies get good at production and marketing via the “learning curve,” i.e., learning by doing. Companies that produce too few for too long may find it hard to catch up to the leaders. SONY found this out when it repeatedly tried, and failed, to put out a competitive personal computer a couple of decades ago.

US companies held back by Trump will face a similar problem. Trump is “Making China Great Again.”

Many companies have scaled back the pace of their BEV growth, but none seem as viscerally antagonistic as Toyota. None are so aggressive in trying to slow others’ efforts. The New York Times revealed that, in the US, Toyota funded candidates opposed to BEVs and initially cheered Trump’s victory due to his anti-BEV stance. This year, it even aided Republicans in Congress who passed a new rule preventing California from doing what it has done for decades: promulgating its own stricter emissions standards for cars sold there. The motive was to lessen demand for BEVs. California mandates that all vehicles sold there have zero emissions by 2035.Since California and twelve other states that follow its rule account for nearly 40% of the US car market, the American anti-BEV faction took unprecedented action, possibly violating the law. The issue is now being fought out in court.

Toyota Thinks It Called The Market Right

Toyota is more convinced than ever that it read the market trends correctly. It points to the record profits it raked in during 2023 and 2024 because it stuck to conventional hybrids (HEVs), when the pace of BEV growth slowed. Yet, the first quarter of this year saw a stunning 42% year-on-year global rebound in BEV sales, compared to 26% each for PHEVs and HEVs.

Moreover, profits today don’t necessarily mean profits tomorrow. Both GM and IBM had record profits shortly before they suffered a few years of record losses that led to fears GM might go bankrupt. Like Toyota, GM and IBM had hugely successful business models that needed replacement. IBM had to hit rock bottom before it recognized that reality.

Traditional companies around the world have a financial incentive to disbelieve radical changes in the marketplace. That’s because they have huge “sunk costs” that they are trying to recoup. In Toyota’s case, these “sunk costs” lie in hybrids. Toyota is increasingly offering its most successful models in hybrid-only versions. That can lead to “confirmation bias,” giving greater weight to any evidence that supports the current strategy and discounting conflicting evidence. The more profits that Toyota makes today, the longer it will take executives to realize that an approach that may seem brilliant in 2025 will be far less suitable in 2030 and beyond.

Could Toyota be right and mainstream analysts wrong? Sure, it’s possible. But it’s very risky for Toyota to put almost all its eggs in the one basket of hybrids.