Reducing the unpopular consumption tax has become a major election issue for the first time since it was first instituted in 1989. All of the significant opposition parties are running in this July’s Upper House election on proposals for a temporary (1 to 2-year) reduction in the tax. The opposition hopes to end the Liberal Democratic Party/Komeito coalition’s majority in the UH just as in the Lower House election last year. While opposition to a hike in the tax has been an electoral issue in the past, never before has even a temporary reduction become a pivotal issue in any election. It has taken on salience this year because of the harm to households from inflation and the potential hit to income from Donald Trump’s trade war.

My own view, to be detailed in this post, is that the consumption tax should be sharply cut, and not just temporarily. The lost revenue can easily be made up by rolling back some of the drastic cuts in the past few decades in the corporate profits tax. The economic rationale will be the primary focus of this post. But first, some more on the politics of the issue.

Where the Parties Stand

Back in 2020, the biggest opposition party, the Constitutional Democratic Party (CDP), ran on a platform calling for just the coupling I advocate: cutting the consumption tax and paying for it by raising the corporate tax. However, in 2024, former Prime Minister Yoshihiko Noda joined the CDP and quickly became its leader. Back in 2012, Noda presided over a hike in the tax, which led to the crushing defeat of the Democratic Party of Japan (a precursor to the CDP and other parties) in 2013 at the hands of Shinzo Abe. He seems not to have learned his lesson. In the 2024 Lower House election, Noda removed both the consumption tax cut and a hike in corporate taxes from the party platform.

Now is the time to revive both parts of the 2020 stance. The LDP is so vulnerable that many of its Upper House members have called upon the party to present its own plan for a temporary reduction, as has the LDP's ally, the Komeito party. In fact, a group of 70 LDP Lower House members called for the tax reduction. However, the LDP leadership says any reduction would be irresponsible if it is not paid for by a tax hike on something else. There’s another factor guiding the LDP's fiscal hawks: the Finance Ministry (MOF) is worried that once the rate is cut, it will be politically hard to raise it back up again. As for the LDP's pretext, the party is banking on a potential weakness of the opposition: none of the parties has said how they would pay for a reduction.

In late April, a severely divided CDP called for temporarily eliminating the 8% tax on food eaten at home for just one year. That was the most Noda and other leaders would allow. Earlier, a 70-member group proposed eliminating it for as long as high inflation lasts. The MOF says it would cost the government about ¥5 trillion annually in revenue. The Japan Innovation Party calls for eliminating the tax on food for two years. The Democratic Party of the People (DPFP) wants to halve the 10% tax to 5% for two years, and finance the cut by expanding government debt. Like the LDP, the DPFP adamantly opposes tax hikes on big companies.

Polls show substantial support for the tax cuts among voters, but this does not necessarily translate into support for the parties campaigning for it.

Why Cut the Consumption Tax?

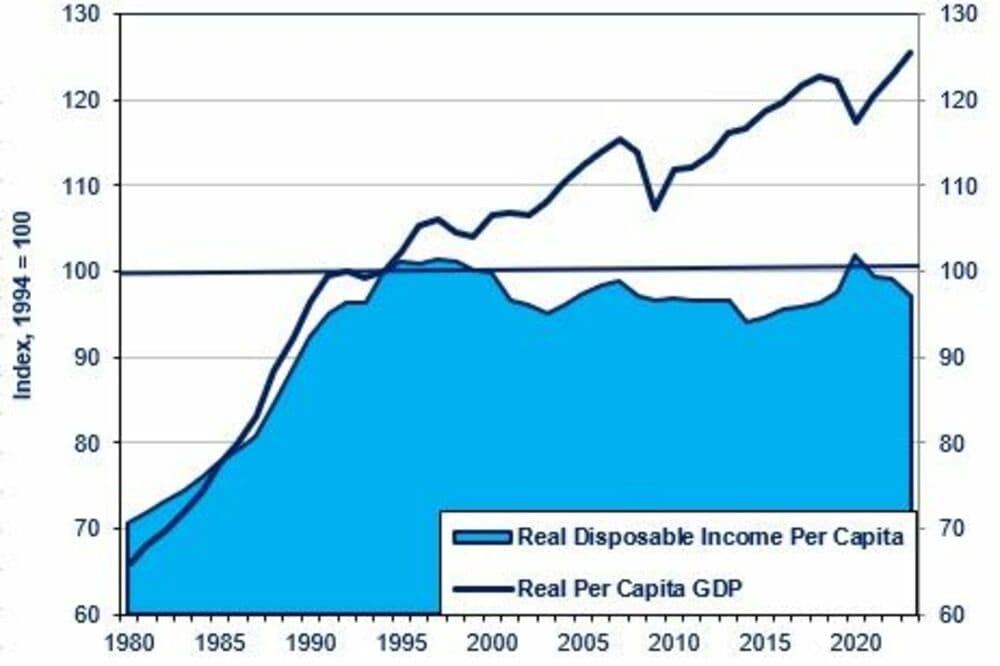

In many countries, a consumption tax is a fine idea. Japan is not one of them. The reason is that, for decades, that tax has added to the numerous policies and practices that have kept real (i.e., price and tax-adjusted) disposable income low, policies that have transferred income from households to corporations. If a tax causes the price of consumer goods to rise 10% and nominal income suffers zero growth, then real income declines 10%. That’s the situation in Japan. Even though per capita GDP (also known as national income) has risen 25% in the past 30 years, real disposable, i.e., after-tax, income per person has not risen at all (see chart below). Aside from Greece, I know of no other rich country where this is the case.

If you take away people’s income, they will naturally find it harder to spend. So, how did Japanese consumers increase their consumption if their income was flat? They did it by saving less. That worked through 2012. But, by 2013, the savings rate had fallen so low—just 0.7% of their income on average since 2013, except for the Covid years—that there was little room to cut more.

Consequently, real consumer spending per capita has barely grown from 2013 through 2024.

If consumer spending per capita is flat and the number of people is shrinking, then companies will not invest in additional capacity in Japan. The overall result is anemic demand and thus low GDP growth. So, the government has to keep running massive budget deficits to make up for slack private demand. If Japan wants to grow, it has to give consumers more purchasing power., That requires cutting the consumption tax, among other measures.

This evidence, by the way, gives the lie to the MOF's excuse that cutting the tax wouldn’t work because people would just save the extra money. The opposite is true. The data shows that when Japanese households have more money to spend, they spend more. If the MOF were right, the savings rate would never have plunged so severely.

Who’s Getting the Extra Money?

If national income is rising but household income is not, who’s getting that extra income?

A considerable portion of it is going to corporations that are hoarding the excess profits. People who claim “Japan is Back” often point to rising profits. But most of those profits come from suppressing wages. Corporate earnings per employee today are twice as high as three decades ago in 1996. But sales per employee—one measure of productivity—are just 20% higher. And wages per employee are virtually no higher at all. Wage suppression transfers income from people to corporations.

Due to the zero-interest rate policy, annual interest income has plummeted 85% from 1990, a big hit to the elderly who depend on that income to pay their day-to-day bills.

In addition, government spending on social security has fallen from ¥2.9 million per senior to just ¥2.1 million, a big hit of 30% in price-adjusted terms.

To make matters even worse, taxes on households—the consumption tax, income tax, and social security premiums—have been raised from 16% to 23% of pre-tax income.

Finance the Tax Cuts With Hikes in Corporate Taxes

The LDP has matched tax hikes on people with tax cuts on corporations, in effect transferring income from households to companies, especially the giants.

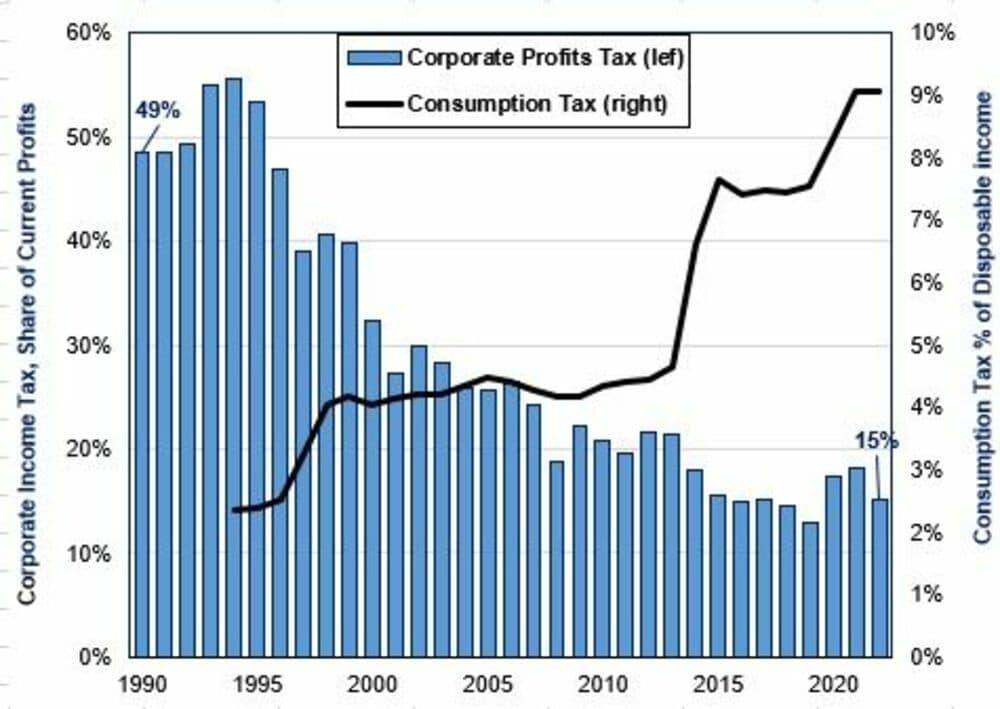

Take a gander at the chart below. The consumption tax has steadily risen over the past 35 years and now takes away 9% of consumers’ disposable income. Conversely, in the early 1990s, companies paid the government 45-50% of their profits in taxes. Now, it’s just 15-18%.

The LDP justifies these repeated tax cuts with the following false claim: if we cut taxes, then companies will use the extra profits to invest more. That will not only increase GDP and thus the tax base, but it will also create more demand for workers and result in wage hikes. Not a single part of this argument has come true, as some mid-level officials in the Ministry of Economy, Trade, and Industry (METI) readily admit, even if their superiors do not. When former Prime Minister Fumio Kishida talked of possibly rolling back some of the corporate tax cuts to finance a doubling of the defense budget, a senior METI official told me that the Ministry’s highest priority was to prevent Kishida from doing that.

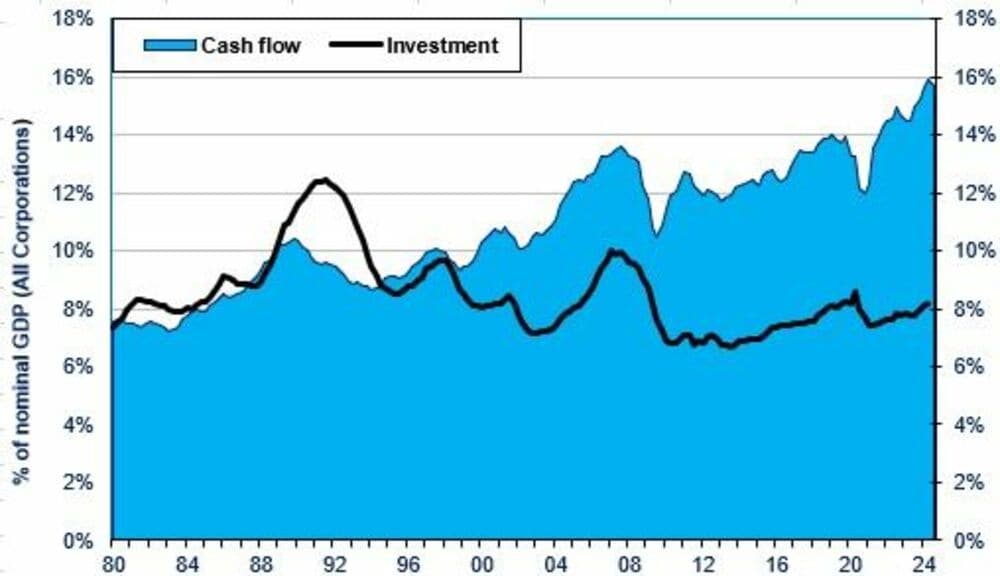

Let’s look at the evidence. Companies typically use their internal cash flow plus loans to finance investment. Cash flow is estimated as the money saved from the depreciation of capital equipment plus half of recurring (current) profits. Now, look at the chart below. Cash flow has risen from 8% of nominal GDP in 1980 to 16% today. And yet, business investment is still the same 8% today as in 1980. So, the excess savings by companies—the gap between their cash flow and their investment—has risen to a stunning 8% of GDP. Some is used to buy corporations overseas, but the majority is hoarded in financial instruments. Investment is low, not because companies lack cash, but because, with consumer spending so low, more investment is not profitable. So, taking back some of their tax cuts would not hurt investment at all.

Companies have enough fallow cash for a hike in the profit taxex to finance substantial cuts in the consumption tax Consider the following: Back in 1990, corporate profits equaled 8% of GDP and half of that was taken by the government in taxes. So corporate taxes totaled 4% of GDP. In 2023, due to wage suppression, profits had doubled to nearly 17% of GDP. However, the government had slashed corporate taxes; the maximum rate was cut from 52% to 31%. As a result, corporate tax revenue was down to just 2.5% of GDP.

If not for these cuts, corporate tax revenue would be 8.5% of GDP today. That’s six percentage points higher. That’s enough to end the budget deficit, which has averaged 5.3% over the past decade. Alternatively, it’s enough to eliminate the consumption tax altogether, and certainly to reduce it. In 2023. 6% of GDP equaled ¥36 trillion. In the same year, consumption tax revenue equaled ¥30 trillion.

So, why are none of the opposition parties calling for a rollback of the tax cuts that lowered the maximum rates on company profits from 52% to 31%? While many Diet members in all the parties do advocate that—as did the CDP in 2020—today’s leadership keeps repeating the myth that low corporate taxes spur more investment.