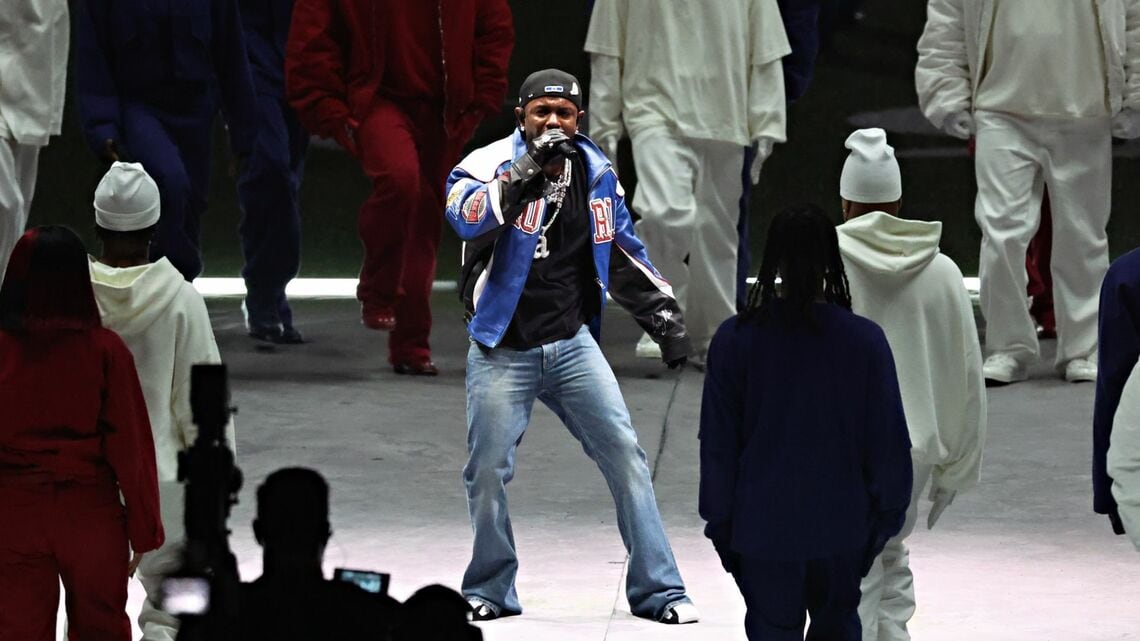

At this year’s Super Bowl, Grammy and Pulitzer Prize-winning rapper Kendrick Lamar delivered a performance of Not Like Us that was more than just entertainment—it was a message.

The song, which became an anthem of resistance in Black America, was initially aimed at a rap rival, but it evolved into something much larger—a cultural moment, a declaration of who gets to define identity.

That message was amplified at the Super Bowl, where Lamar’s performance became more than music; it became a statement—delivered right in front of a sitting president working to erase Black voices from history.

The timing was no coincidence. The month of February is Black History Month (BHM) in the United States, an observance created to counteract the historical erasure of Black contributions to American history.

But now, with Trump and his allies dismantling diversity, equity, and inclusion (DEI) programs, banning books, and silencing discussions on race, BHM itself is under threat. The erasure of Black history is no longer just an ideological battle—it is active policy.

“They not like us,” the phrase chanted by Kendrick and his audience, was a defiant response to a long-standing truth in America: there has always been an us and a them.

For centuries, Black Americans have been treated as outsiders in their own country, their history dismissed, their contributions minimized, and their very citizenship contested.

Now, as history itself is being rewritten to exclude them, the phrase Not Like Us takes on new weight—not just as a song lyric, but as a statement about the continued struggle for recognition.

This idea—of defining who belongs and who does not—is not just an American phenomenon, by no means. I’ve seen it play out here in Japan as well.Japan has long prided itself on its homogeneity, a feature often framed as a source of strength. But with this homogeneity comes an implicit understanding of uchi (inside) and soto (outside).

When encountering a conspicuous non-Japanese person, there is often an instinctive moment of recognition: They are not like us. Sometimes this reaction stems from curiosity or admiration, but in my experience it often leads to fear and exclusion.

The distinction between inside and outside is deeply ingrained in Japanese society, shaping how individuals interact with foreigners, immigrants, and even those of mixed heritage.

For hāfu—biracial Japanese individuals—this dynamic is even more complex. While legally recognized as Japanese, many find their identity questioned in daily life.

Their nationality is often met with skepticism, and their ability to “truly” be Japanese is frequently challenged. Black hāfu, in particular, navigate a unique set of experiences, as their visibility makes assimilation into their own society even more difficult.

In many ways, their challenges mirror those of African Americans in the U.S., who, despite being full citizens in every legal way, have historically been treated as outsiders within their own country.

Even language plays a role in this dynamic. The ability to speak English, for example, is often recognized as a status symbol in Japan, associated with global sophistication and opportunity. Yet, this association can further reinforce the idea of otherness, as Japanese people who are fluent in English may be perceived as having a degree of foreignness themselves.

These questions of identity and cultural perception extend beyond social interactions. Japan, like Black America, has also had to contend with the influence of Europeanization. After the Edo period and especially following World War II, Japan underwent rapid modernization, often adopting Western benchmarks as the new standard of sophistication.

European Classical music became the pinnacle of musical excellence, ballet the highest form of dance, and European traditions the markers of refined culture.

This shift was not necessarily seen as a rejection of Japanese identity, but over time, it subtly reinforced an idea that Western—meaning European and white—standards were the measure of progress and success.

A similar process occurred to Black people in America, where assimilation often required adopting European cultural norms. From language to fashion to education, success was frequently defined in terms of proximity to whiteness.

The effects of this shift are often so ingrained that they go unnoticed, shaping perceptions of excellence in ways that persist across generations.

However, while Japan adopted Europeanization as part of its modernization efforts, Black Americans were forcibly subjected to it, with devastating effects on cultural identity.

The historical suppression of African traditions and the imposition of European ideals created deep psychological wounds, reinforcing the notion that true success could only be achieved by adhering to white standards.

To counteract this, Black communities took it upon themselves to reclaim their narratives and build institutions that reaffirmed Black identity.

The school I attended as a child – called Uhuru Sasa Shule (swahili for “Freedom Now School”) was created for precisely this reason—to offset the damage Europeanization inflicted on Black minds and souls.In public schools, Black history was either erased or distorted, reinforcing the idea that Black people had contributed little to civilization.

My school, however, took an entirely different approach. Every day was Black History Day. Our curriculum centered on Black excellence, teaching us that we were heirs to a great legacy of mathematicians, scientists, artists, and leaders. It sought to undo the psychological effects of forced assimilation by embedding in us a sense of self-worth rooted in our true history.

The push to erase or revise Black history in America is not just about the past; it is about controlling the future. When certain narratives are removed from public consciousness, it shapes how a society sees itself and others.

Japan, too, has had to navigate how it remembers its past—both within its borders and in its relations with neighboring countries. History is not static; it is constantly being rewritten based on the priorities of those in power.

Understanding Black history is not just an American issue. It is a reminder of how narratives shape identity, belonging, and power dynamics across cultures.

While Japan does not have the same racial history as the U.S., its own discussions on identity, inclusion, and historical memory make the lessons of BHM relevant beyond American borders.

When I was a child, my school made sure me and my classmates knew that our greatness was not a footnote but a central chapter in human history. That blackness is exceptional.

This perspective was empowering, but as I grew older, I realized that nearly every culture tells itself a version of this story. Many societies hold deep-seated beliefs in their exceptionalism, often using history as a way to reinforce those narratives.

Living in Japan for two decades has given me a different lens through which to examine these ideas. Japan, too, has narratives of uniqueness, of being unlike any other nation. And while this pride can be a source of strength, it can also create barriers to inclusion, making it difficult for those who do not fit the traditional mold to feel fully accepted.

I’m told by my Japanese freidns and family that this is unintentional, and I accept that on face value. But lately I’ve begun to wonder, is this human nature?

To me, Lamar’s Not Like Us performance wasn’t just about a ridiculous rap feud—it was, the Pulitzer-winning rapper’s statement on the sign of the times. A reminder that history, identity, and power are always in play. That even as some try to erase the past, others fight to reclaim it.

And that message resonates far beyond America.The phrase Not Like Us has echoed in different forms throughout history, in different societies. In America, it has fueled both oppression and resistance. In Japan, it operates more subtly but with lasting consequences.

The question isn't just who “they” are—but who gets to decide what “like us” and “not like us” actually mean.Because whether in politics, history, or culture, identity is still the game. And the rules—who belongs and who doesn’t—are still being rewritten.