As Liberal Democratic Party members struggle to pick the next Prime Minister of Japan, there is a vote that will not be counted but matters a lot – who does Washington want to be Japan’s next leader?

The most obvious answer to that question is that Washington doesn’t care. At the senior levels of government and policymakers, “they could care less,” a former senior government official who remains deeply engaged with Japan told Toyo Keizai. “At the expert level, there are preferences. But no one in Washington is talking about it all.”

One reason for this lack of interest is also obvious – Americans are deeply engaged with their own, highly contested election. But the unique nature of the Japanese party election makes it confusing, not least because of the very large field of candidates. And ultimately, Americans assume, perhaps wrongly, that the result of the election is not going to change Japan’s foreign and domestic policy.

Still, for American policymakers and experts, it matters who emerges as Japan’s next leader. What is most important for the United States is “who can be an effective leader that re-energizes the Japanese public, that delivers an economic agenda that is sustainable, that allows Japan to keep up its defense expenditures and encourages the Japanese economy to be a key hub in global supply chains,” says Mireya Solis of the Brookings Institution, one of the premier Japan experts in Washington.

“Folks in Washington are looking for somebody who will continue the Abe [Shinzo] alliance policies, expanding the alliance, and expanding what Japan can do within the alliance,” says Amb Joseph Donovan, Jr, a former senior State Department official with extensive experience in Japan.

Along with that, Americans are looking for “somebody who can work with the ROK (South Korea), and somebody who has strong domestic support, who can bring the LDP back together.”

That said, Donovan and others I spoke to offer a “huge caveat” – what might happen if leadership changes in the U.S.

If Democrat Kamala Harris prevails, she “will be looking for the strongest possible Japanese Prime Minister,” says the former senior official, who wished to remain anonymous. “Whereas Trump will be looking for which Prime Minister he can manipulate.”

Abe was able to “both impress the U.S. President and also stand up for Japan. It is really important that whoever meets with Trump is able to exude self-confidence as a global leader.”

Within that broad framework, Japan offers its own views on who might best fit those requirements.

How Washington sees the candidates

Leaving aside the question of the ability to project a reformist image that can rally voters back to the scandal-tarnished conservative ruling party, American policymakers tend to favor the most experienced figures in the LDP, particularly those who have long interacted with Washington.

“Everyone in Washington DC would be thrilled if it were Hayashi [Yoshimasa],” said Tobias Harris, the biographer of Abe and author of the widely read “Observing Japan” newsletter.

“Obviously, he has lots of friends here. He worked on the Hill (Congress). He is the continuity candidate. If you like what the Kishida government has been doing, then Hayashi is your guy.”

Washington knows the other candidates well: former Foreign Minister and current LDP Secretary General Motegi Toshimitsu, the current Foreign Minister Kamikawa Yoko, and former Foreign and Defense Minister Kono Taro. The former senior government official offered this frank, off-the-record assessment of the three, based in part on personal contact.

Motegi’s experience with Washington comes mainly in the trade area, as the negotiator of the Trans-Pacific Partnership and dealing with the Trump administration.

“He is smart, effective, a little bit aggressive – not a typical Japanese, but Americans can deal with that,” says the former official. “He is abrasive, but that doesn’t matter in international affairs.”

As for Kamikawa, “she is the opposite. It's so nice, vanilla-flavored. Washington would think she is chosen because of her gender and being fluent in English.”

Kono is also a potential Prime Minister with long experience in Washington, someone fluent in English, “spends a lot of time with Americans and knows the U.S. reasonably well,” the former official says.

But there are concerns about Kono, particularly in the Pentagon but also the State Department, mainly arising out of his time as Defense Minister and the abrupt cancellation of the Aegis Onshore missile defense program, which shocked Washington. “Kono thinks Americans like him, but that is not true.”

As things stand now, however, none of the ‘experienced’ candidates seem likely to make the final two. That leaves a set of candidates who are not at the top of American lists—former Defense Minister Ishiba Shigeru, former Economic Security Minister Kobayashi Takayuki, Koizumi Shinjiro, and current Economic Security Minister Takaichi Sanae.

None of these possible leaders is considered a serious problem for alliance relations—except for rightwing stalwart Takaichi, who has positioned herself as the ideological heir to Abe’s more nationalist agenda.

“Takaichi would make everyone nervous,” says Harris. Her provocative stance on wartime history issues, including plans to make official visits to the Yasukuni shrine to Japan’s war dead, “would upset the apple cart on trilateral ties with the Koreans.” Those worries extend to Koizumi and Kobayashi, who might also visit Yasukuni and sour relations with Korea.

Takaichi appeals to more hawkish elements in Washington, particularly among Trump backers, who see her as more willing to militarily confront China. “She is going to want the same things that some people in Washington want, and they will find a way to work with her,” says Harris.

That view does not extend to other experienced Japan hands in Washington. “It is hard to be too hawkish in Washington these days, but she might be too hawkish for the Washington crowd, at least among Japan hands,” predicted the former senior official.

Ishiba is perhaps the most intriguing and potentially difficult leader for Japan among Americans. Although he garners considerable attention in Japan, he is not that well known in the U.S. He has some support in the Pentagon from his experience as Defense Minister and his interest in weapons development. But he has a reputation as a Japanese Gaullist, someone willing to forge a more independent path for Japan.

“Ishiba is sincere,” comments Harris. “He says what he thinks, and he comes from this tradition that is not going to do what the U.S. wants if it is not in Japan’s interests.”

Harris compares him to Kono, noting that both men have been critical of the protectionist decision to bar Nippon Steel’s purchase of U.S. Steel. Both men represent “a Japan that can say no, maybe politely, but still say no.”

Ishiba reflects more openly a widely held worry in Japan about U.S. reliability, particularly under a second Trump administration. “He and Trump together talking about burden sharing would be an interesting conversation,” says the former senior official. “He will give as good as he gets.”

The other candidate coming out of the former Abe faction, Kobayashi, is garnering more interest in Washington where some think he could emerge as the second-place candidate. Compared to Takaichi, he is viewed more favorably.

Kobayashi is “very bright, a good communicator, with U.S. experience,” says the former official.

“He is young, interesting, probably someone the U.S. could work with, but who is really going to make decisions if he is Prime Minister.” His interest in economic security is much appreciated by Washington policymakers.

The Koizumi question

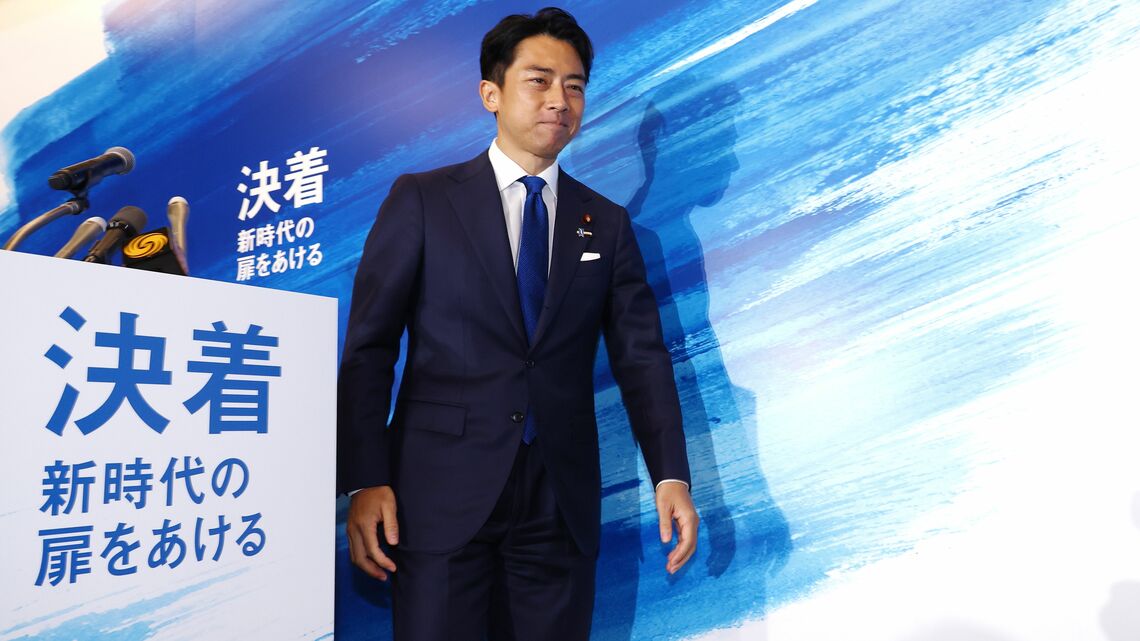

That brings us to the last viable option and the current front-runner in opinion polls – Koizumi Shinjiro, the son of the former Prime Minister. He is clearly popular and offers the best chance to restore the damaged image of the LDP.

He has had little to say on foreign policy, focusing almost entirely on internal issues of political reform and encouraging entrepreneurial-led growth.

Koizumi is well-known in American policy circles. His graduate education at Columbia University was followed by an invaluable internship at the Washington think tank Center for Strategic and International Studies, working closely with veteran Japan alliance manager Michael Green. But there are questions about both his lack of experience and his policy views.

“He doesn’t get deep on policy very often,” the former official told Toyo Keizai. “People here would think they have chosen someone attractive to voters, but let’s see if he can handle the job.”

Nonetheless, in a second-round contest between Koizumi and either Ishiba or Takaichi, the Washington experts would tend to favor the young politician.

They assume he would have the backing of the LDP’s heavyweight kingmakers like Aso Taro and Suga Yoshihide and would represent a unified party.

For American Japan hands, the bottom line is to have a leader that can continue to project a more assertive role in global affairs.

“If you have a leader that is not strong, that could mean Japan is not going to be as proactive as it has been in the past,” says Brookings’ Solis, author of an important new book on Japan’s leadership role.

Japan has become a key voice in opposition to the deepening of economic nationalism that is “flourishing in the U.S.” and the growth of xenophobic populism. The possibility of a return to isolationism under Trump underlines the importance of Japanese leadership, she says.

None of the possible candidates for LDP leadership would be as disruptive as the experience with the brief period of Democratic Party of Japan rule.

“It is more a question of what kind of Prime Minister is more adept at taking the reins of government in Japan, of providing good economic management assuring that the LDP can get through its agenda.

“If you see a weakening of that control power that we got used to, that brought a more decisive Japan, that would be a challenge.”