It was a thrilling moment. The Japanese Prime Minister vowed to raise to 30% the number of female managers at private companies—and to do so in 13 years. That PM was Junichiro Koizumi, and the promise was made in 2003.

Ten years later, Shinzo Abe repeated the 30% promise with the same 2020 deadline. Two years later, he halved the target to 15%. Now, nearly another decade has passed, and yet another

Prime Minister, this time Fumio Kishida, has vowed that 30% of corporate executives will be women. Once again, seven years is the promised timeline.

Kishida, like Abe and others before him, has a habit of announcing lofty goals without creating any effective measures to turn the goal into reality. He says he is appointing a committee to come up with measures, but he has done the same regarding other big issues—from creating startups, to raising the birth rate, to fixing the maldistribution of income, and reviving nuclear power plants—with few actual accomplishments

Moreover, Kishida’s goal is far less ambitious than that of his predecessors. Kishida referred only to executives, not all managers. Moreover, he posed this goal only for the top companies in the prime section of the stock exchange, where only a sliver of Japan’s workers is employed.

So far, empty promises are working for Kishida, if not for Japan. His poll ratings, while bouncing around, are high enough to keep him in power. So, he has little incentive to change.

Glacial Progress

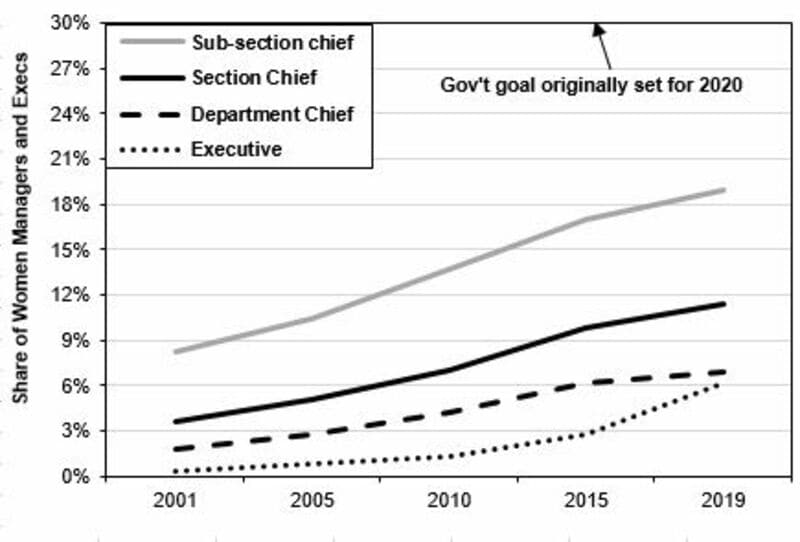

No one doubts that progress has been made on women’s equality in companies, but the pace has been glacial. Twenty years ago, women held just 8% of kakaricho posts. That’s the first rung on the managerial ladder, and one attained by almost all men. By 2019, the female share was up to 19% (the most recent data available). During the same period, the female share of kachos rose from 3.6% to 11%. Among buchos, it has risen from 1.8% to 6.9% and executives from nearly zero to 6.2% (see chart below).

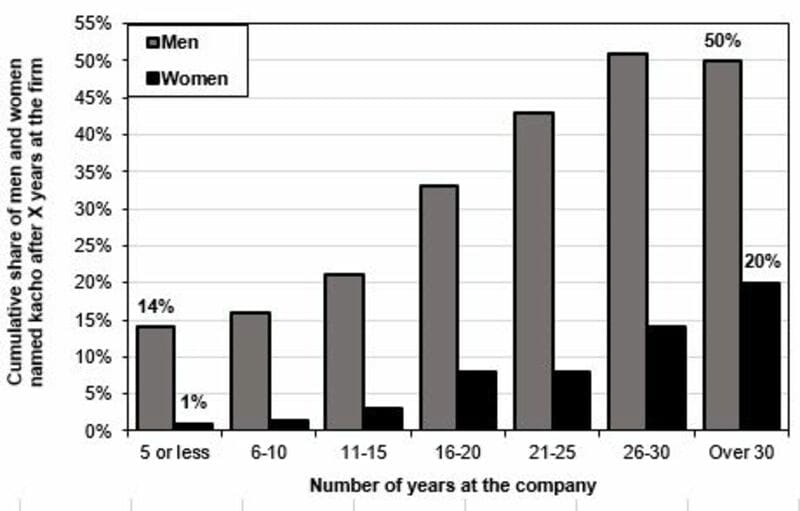

The women who do get managerial roles acquire them much later in life. Within five years of joining the management track at a sizeable firm, 14% of men have reached the kacho level, but just 1% of the women. By the 20th year, a third of the men have attained the level of kacho or higher, but just 8% of the women. That limits the opportunity for future promotion all the way up. How can women become 30% of executives if so few have even reached the bucho post (see chart below)?

Many firms seeking to show good numbers give women a managerial title but not the authority and experience that normally come with that. In her 2016 book, Too Few Women at the Top, Kumiko Nemoto cites a thirty-eight-year-old male deputy general manager in a bank’s investment banking section, who reported that he does not see many female managers in the workplace who possess real organizational power.

“Many of them have been given the job title but no subordinates to manage.” One wonders how many of the supposed female executives have real power at larger companies.

Moreover, women are often forced to choose between career advancement and family life. According to a 2014 survey, 81% of male managers had children, but just 37% of female managers.

Partly this is due to outright “maternity harassment,” which is illegal, but often just because the responsibilities of parenting make it harder for many women, especially those without childcare help, to spend the time required of a manager. Only some firms try to ameliorate this problem.

Japan Ranks 133rd

If the government wants to have more women managers, get equal wages, etc., the first step is just to enforce the law, which outlaws gender discrimination on wages and promotion. And equal promotion is just one part of the problem.

Women are paid less even when other factors, like occupation and education, are equal. Men and women with university degrees start at around the same pay at age 20-24. By the time the male reaches 50-54, his pay has almost tripled, but a woman’s pay has just doubled.

According to the World Economic Forum’s 2023 report, among 146 countries, Japan ranked 133rd for leadership roles in government and companies and 75th for wage equality for similar work (even worse than the rank of 67 in 2020).

Having lower salaries means women accumulate less money to pour into a firm, so a female-founded firm is likely to be smaller and hence less successful. So, there are far fewer female entrepreneurs. Beyond that, banks are even more reluctant to lend to women. Only 12% of female-owned startups got bank loans vs. 26% for men.

Mr. Kishida: Just Enforce the Law

All this discrimination is at odds with Japan’s Labor Standards Act, whose words seem quite clear: “An employer shall not engage in discriminatory treatment of a woman as compared with a man with respect to wages by reason of the worker being a woman.”

In addition, the 1986 Equal Employment Opportunity Law (EEOL) forbids discriminating against women on matters of promotion, or even using criteria that appear to be gender-neutral but result in discrimination. These laws are routinely ignored and there is no government agency mandated to enforce them. The victim must spend her time and money seeking redress in court. Worse yet, class-action lawsuits are not available in such cases.

A lawyer who always represents companies in such suits told me that his clients routinely get around the “equal pay for equal work” principle by tweaking the job description, to argue it is not really equal work. Judges almost always back the employer in such cases. Even when, in response to complaints, a government agency finds that a firm has violated the law, it is just given an administrative order to rectify its practice but is not penalized.

By the way, the same anti-discrimination laws apply to non-regular workers, and there is no enforcement in that case either.

Partly in reaction to the anti-discrimination clauses of the EEOL, firms created two separate tracks: ippanshoku dominated by women and nicknamed “the mommy track” and the sogoshoku dominated by men.

At age 45, a person on the management track will earn nearly 2.5 times as much as his counterpart on the general track. As late as 1992, 40% of firms felt no shame in justifying the track system by saying that they put women into jobs “for which the female sensitivity can best be used.” Although few companies would dare say this out loud today, their record on promotion suggests that many still have that attitude.

The solution is to mandate that the Labor Ministry investigate and penalize violations of the law. Japan does have labor inspectors who examine the practices of individual companies. But mostly, they focus on violations like excessive overtime or lack of payment for overtime. They regard matters of equal pay as a contract dispute and not within their purview. Plus, there are too few inspectors to seriously investigate this issue, only about 3,000.

If Kishida wants to be serious, he would mandate that these inspectors investigate discrimination on pay and promotion, and he would ensure that the Labor Ministry penalizes violations via stiff fines and publicity. Despite talk of “womenomics,” Abe declined to take this obvious step. Kishida’s track record on matching goals with measures does not give much reason to hope that he will do any better.