In the battle between the financial markets and the Bank of Japan (BOJ), who is winning? There is no question that market pressure forced the Bank of Japan on December 20 to do something it did not want to do: lift the maximum rate of 10-year Japan Government Bonds (JGBs) from 0.25% to 0.5%. But no one knows what this means for future moves in interest rates, the value of the yen, or financial market stability.

For example, the yen leapt from ¥137 before the BOJ move to ¥131 the next day in New York. But much of this comes from traders betting that this rise in interest rates will be followed by further ones. Financial markets often gyrate in response to a big surprise. So, it remains to be seen where the ¥/$ will stand in the coming weeks and months, as the market tries to size up the battle between bond traders and the BOJ.

BOJ Governor Haruhiko Kuroda believes that he simply opened a “steam valve” to release the pressure and that the BOJ will be able to continue keeping interest rates at ultra-low rates. The move “was not a rate increase,” he told a news conference, but rather a technical measure aimed at “improving market functioning.” He moved because some distortions in the market for JGBs (to be explained below) were spilling over into the market for corporate bonds and some other financial markets. Raising the maximum rate on 10-year JGBs, insisted Kuroda, was not the first step in an exit from the BOJ’s decade-long strategy. “We have absolutely no intention of raising interest rates or tightening monetary policy.”

BOJ officials have repeatedly stated that they want to see wages rise at least 3% per year on a sustained basis before they believe it is safe to lift interest rates. Some officials hope Rengo’s demand for a 5% wage hike in this year’s shunto negotiations means that the wage picture is changing. But, if, as economists now predict, the US and Europe will likely enter recession in 2023, it’s hard to see much wage generosity from Japanese companies.

Many—but hardly all—traders believe Kuroda will be unable to persist in his stance. Having forced the BOJ’s hand once, market pressure can force it again, perhaps a few months down the road. The BOJ, in this view, has begun a de facto exit from Kuroda’s decade-long policy, even if the BOJ doesn’t realize it yet. Traders in this camp believe the next move could take place before Kuroda’s term ends in March or under the next Governor.

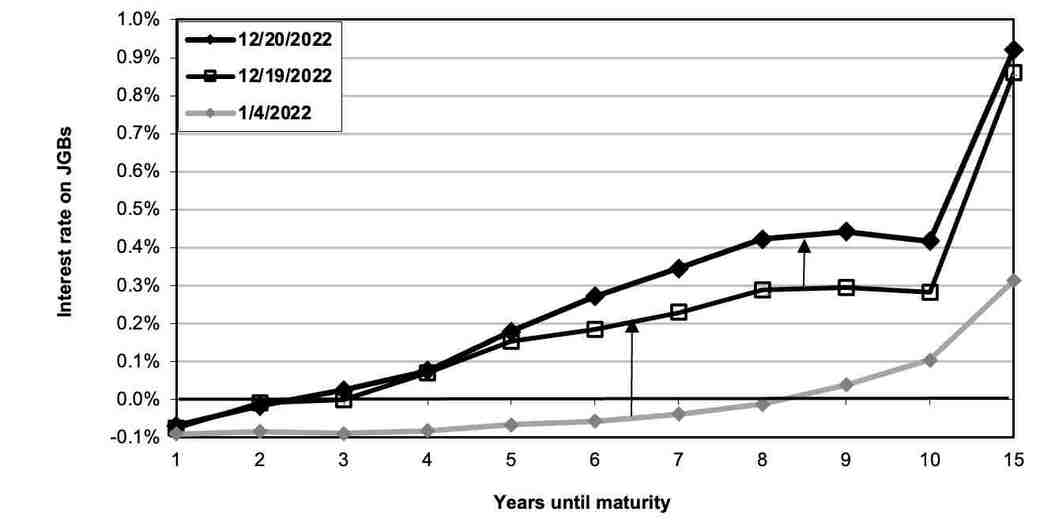

This faction of traders points to two facts to justify their view. Firstly, although the BOJ only acted in regard to the 10-year JGB, rates rose all along the so-called “yield curve,” as seen in the chart below. That curve shows the rates on JGBs ranging from as little as one year all the way to 40 years. Rates are now far higher than they were at the start of the year when rates were negative on bonds with maturities as long as eight years.

Secondly, the BOJ’s policy of “yield curve control” has caused a big distortion in both the government and corporate bond markets. Normally, as seen in the bottom line in the chart, the curve goes steadily higher as maturities of the bond get longer. However, since the BOJ only defended the 10-year JGB rate, the market in recent months was able to force the interest rate on eight and nine-year JGBs to a level higher than that on the 10-year bond. Traders point out that this distortion continues to exist even after the Dec. 20th move. Hence, if the distortion made the BOJ move once, they argue that it will inevitably force it to move again.

While it’s impossible to tell which side is right, we can look at some factors that will shape the outcome.

Firstly, if the BOJ is willing to spend enough money buying JGBs at all maturities, it can keep rates down. In fact, the BOJ just announced it will hike its purchases of JGBs from ¥7.3 trillion to 9 trillion yen per month, and will purchase as many 10-year JGBs as necessary to prevent the rate from going above 0.5%.

However, that means that the BOJ, which already owns more than half of all JGBs, will own more and more. And that will increasingly cause problems for insurance companies and pension funds, which need to hold bonds as a source of income. JGBs now account for more than 35% of all assets of insurers and pension funds, down from 39% when Kuroda became Governor. Banks had also stocked up on JGBs as loan demand slowed and they grew to 18% of bank assets in 2012; now it’s down to 6%.

Secondly, an abrupt and substantial rise in interest rates would have severe consequences. As rates go up, the value of existing bonds held by banks, pension funds, and insurers goes down, straining their balance sheets. Meanwhile, a quarter-century of near-zero interest rates has created a host of Japanese companies addicted to essentially free money. Today, 37% of all bank loans charge less than 0.5% interest, and, among these, half charge less than 0.25%. Given slack demand for loans, it is not clear how much bank lending rates would rise in tandem with JGB rates.

However, if bank lending rates did rise even one or two percentage points, many companies with millions of employees would suddenly look a lot less solvent. Many of them would have to be bailed out by the government, which has issued credit guarantees and direct loans to about 40% of all SMEs. These add up to about 11% of GDP. However, the credit guarantees cover a maximum of 80% of the loan and so banks would suffer a surge in nonperforming loans.

A third factor is the value of the yen. The steep fall of the yen over the past year and a half has been a big factor in the rise of Japanese inflation. In fact, 90% of the rise in prices during this period has come in the import-intensive food and energy sectors. That has been a big hit to consumer purchasing power. To the extent that the yen regains some of its lost value, that will reduce inflationary pressures and thus pressure on the BOJ to raise interest rates.

Finally, there is the course of inflation. Kuroda believes, and correctly so, that most of Japan’s inflation is caused by the yen’s depreciation and the impact of supply chain blockages. Hence, he contends that Japan’s current inflation is temporary.

In its October Outlook for Economic Activity and Prices, the BOJ predicted that, after rising 2.9% in fiscal 2022, inflation would decelerate to just 1.6% in 2023 and 2024. That’s lower than the BOJ goal of 2%. If the BOJ is right, then pressure on it to hike rates will ease. However, the BOJ does not have a good track record in its forecast. For example, just three months earlier, the BOJ’s July Outlook predicted inflation in fiscal 2022 would be 2.3% instead of the 2.9% it predicted in October. If the BOJ is wrong about 2023, it will face more pressure.

According to a Japanese proverb, in life and politics, an inch ahead lies darkness. The same can now be said of financial markets and BOJ policy.