In the short term, praying that America’s inflation rate plunges may be Tokyo’s only option to deal with the ultra-weak yen. In the long term, however, Japan has to strengthen the underlying competitiveness of its companies because that is the underlying cause of why the “real” yen is the weakest it has been in a half-century (we’ll explain below the definition and economic significance of the “real” yen). The yen is so weak because Japan’s companies have lost their vigor in international markets.

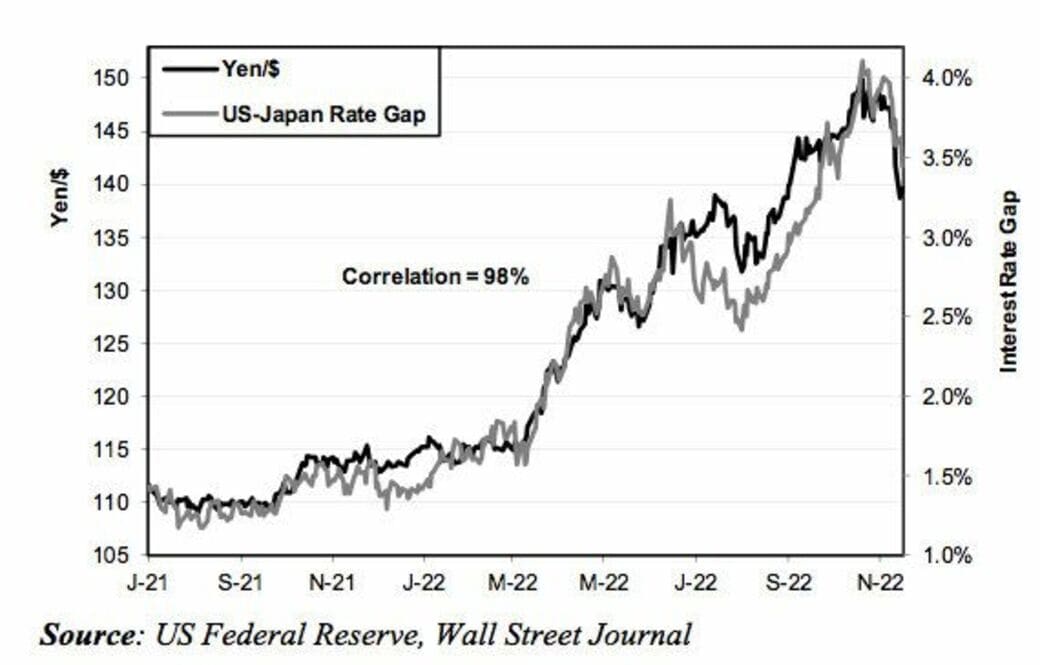

Let’s deal with the short-term first. Over the last year and a half, the single biggest factor in the yen’s weakness has been the gap between American and Japanese interest rates. And higher interest rates are America’s weapon against high US inflation.

The bigger the gap between US and Japanese rates, the more money is lured from Japan to the US, hence the more that the yen weakens. Conversely, as was seen on Nov. 10th when the ¥/$ suddenly strengthened from ¥146 to ¥139, a reduction in US inflation sets off a decline in US interest rates and thus a rebound in the yen. In short, America’s inflation figures have far more impact on the yen than anything the Bank of Japan (BOJ) can do.

There are those who say the Bank of Japan (BOJ) should raise interest rates to boost the yen. However, a quarter century of near-zero interest rates has turned Japanese companies and the government into low-interest-rate addicts.

Today, 17% of all bank loans charge interest rates of less than 0.25% and 37% less than 0.5%. Consequently, a host of zombies that currently give the illusion of being solvent would suddenly face a debt crisis if forced to pay higher rates. In short, the economy is too fragile for the BOJ to raise interest rates enough to make much of a dent in the 3.5-to-4 percentage point gap between US and Japanese rates.

Weak Yen Reflects Weakened Competitiveness

If the gap in interest rates were the only reason for a weak yen, then the yen could bounce back as inflation and interest rates returned to normal. However, the yen’s historic low also reflects a dramatic deterioration in Japan’s fundamental competitiveness.

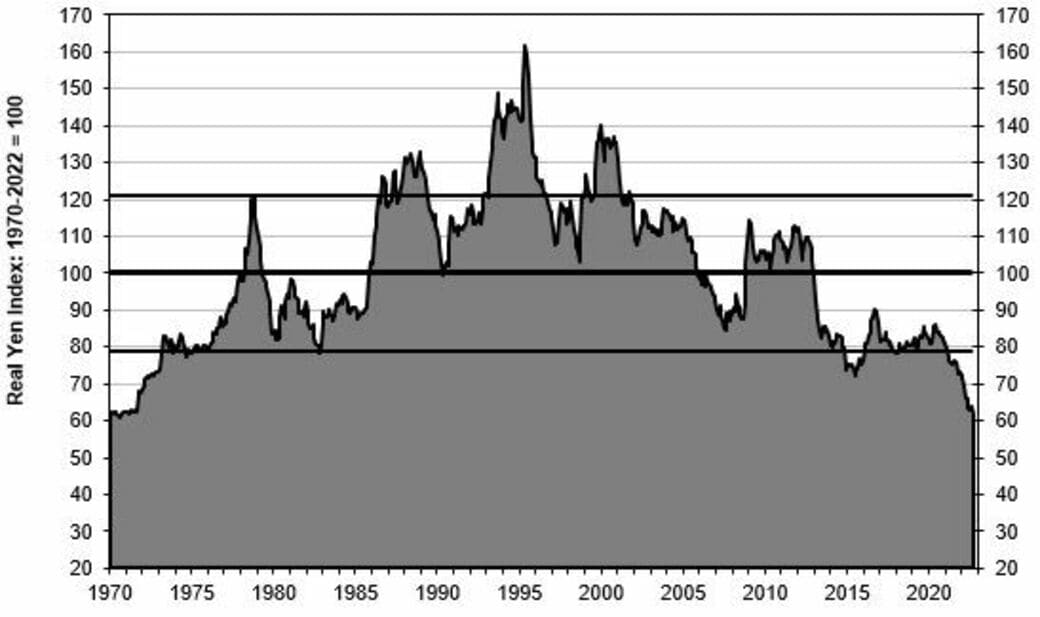

As noted above, the “real” yen is the weakest it has been in 50 years. The real yen adjusts the rate of the yen vis-à-vis all of Japan’s trading partners for the difference in price trends between Japan and the rest.

Here’s why that’s important. Firstly, the real yen measures the prices that Japanese exporters are able to charge their overseas customers. A weaker yen means Japanese companies now have trouble exporting unless they charge very low prices. They can no longer command a price premium based on quality and innovative features.

Worse yet, they’re no longer producing enough must-have products, e.g., a globally-competitiveness smartphone. At the same time, a weak real yen means that Japanese consumers and small-and-medium companies (SMEs) now have to pay much higher prices for import-intensive products like food and energy.

In fact, the yen is so weak that, at any particular gap in interest rates, the yen is about 20 points weaker today than it would have been 10-to-20 years ago. So, even if the gap in interest rates were to fall back to 2 percentage points, the yen/$ rate would still be around 120, whereas in 2000-2012 it would have been around 100.

What is most alarming is that, even with a weaker yen, Japanese companies still find it hard to compete. Japan used to enjoy chronic trade surpluses even when the yen was much stronger than today.

But, for more than a decade, Japan has suffered chronic trade deficits, even though the real yen has been 30% cheaper in the last decade than it was during 1994-2012. Japanese companies are like a deconditioned person on an accelerating treadmill; he has to try running faster and faster but still has trouble keeping up.

Even former superstar industries like electronics now run chronic deficits. Electronics exports are falling while imports are rising. In 2000, Japan’s electronics companies enjoyed a trade surplus of ¥7 trillion, an amount equal to 1.3% of GDP. By 2018, that had turned into a trade deficit of ¥1.2 trillion.

Moreover, these companies have trouble competing even when they produce in other countries with lower costs. Despite a 40% surge in global electronics sales from 2008 to 2020, every one of Japan’s top ten electronics hardware manufacturers saw its global sales slump during that period. Moreover, from 2010 to 2020, total global sales of Japanese electronics firms plunged by 30%.

Weak Yen Makes Japan Even Weaker

The weak yen is not just a symptom of Japan’s economic ills; it also makes the syndrome worse. The BOJ is wrong when it claims a weak yen provides a net benefit to Japan. It’s the Goldilocks principle: a currency that is too weak causes as much damage as one that is too strong. Most Japanese economists now disagree with the BOJ on this issue.

On the one hand, the weak yen does not help Japan’s exports and GDP as much as it used to. On average these days, improvement in Japan’s real (price-adjusted) trade balance contributes a meager 0.1% to Japan’s real GDP growth per year, an amount equal to a rounding error. That’s no higher than it was a couple decades ago the yen was much stronger.

On the other hand, the weak yen is seriously reducing real wages, consumer purchasing power, and the profitability of small and medium companies. That’s because it causes big price hikes in import-intensive food and energy. 90% of the rise in total prices over the past 18 months, as well as in the past decade, has come in food and energy. Prices in the rest of the economy rose only 2% in the entire decade from 2012 to 2022

This is far from the healthy 2% inflation that the BOJ tried, and failed, to produce. Price hikes driven by imports transfer income from Japanese households to foreign producers. It also indirectly transfers income from Japanese households to Japan’s multinationals.

Here’s how the latter works. Japan’s consumers pay more of their income to foreign producers. Some of that comes back to Japan’s multinationals because they can export more and because their profits on overseas affiliates generate more yen when those profits are repatriated.

The weak yen was part of the reason—in combination with wage suppression and hikes in the consumption tax—that priced-adjusted household consumption in 2019 (before Covid) was 1% lower than it was in 2013 and today it’s 2.6% lower than in 2013. There has never before been such a long-lasting drop in household consumption throughout the postwar era.

What’s The Solution?

What is required are reforms that improve Japan’s underlying productivity and innovativeness, once more making Japanese firms competitive in the global marketplace. The yen shock is sounding the alarm. The question is whether policymakers can really hear the alarm and finally adopt many of the helpful proposals made by foresighted Japanese experts.

For a video of an English-language discussion on all this between me and a leading Japanese economist, see here.