When the yen reached a 20-year low of ¥125/$ on April 11, a majority of forecasters told a survey it would weaken to ¥130 by the end of the year. Instead, only eight days later, it hit ¥129. It’s unclear how low and how fast the yen will continue to decline, and how much zig-zagging there will be along the way. Markets don’t move in a straight line.

The specter of an out-of-control flight from the yen is setting off alarm bells in Tokyo, especially with an Upper House election just a few months away. There has already been talk in the press of currency intervention by the Ministry of Finance (MOF) if the yen drops to ¥130. There was also such talk when the yen dipped to ¥125.

So far, Finance Minister Shunichi Suzuki is trying verbal intervention. No longer restricting himself to saying that the speed of the depreciation is too fast—the usual comment—he’s now saying that the level is too low, which is unusual.

“In a situation like now when companies have yet to sufficiently raise prices and wages, a weak yen isn't desirable. In fact, it's a bad yen decline,” he declared. Even Bank of Japan (BOJ) Governor Haruhiko Kuroda, who keeps insisting that a weak yen is a “net positive” for Japan, is now calling the speed of the fall too “sharp.”

Increasingly, economists in the private market are siding with Suzuki, not Kuroda. Keidanren chieftain Masakazu Tokura got into the fray, saying that, “In the past when the yen weakened, trade balance, current account and the economy were all good. It's no longer that simple.”

In a December survey of 7,000 companies by Tokyo Shoko Research, almost 30% said a yen rate this weak hurt their business, while only 5% said it helped. Among those who suffered from the weak, on average they named ¥107 as the best rate for them.

The reality is that there is little the MOF can do that will have lasting effect. Currency intervention only works when gyrations have taken on a momentum of their own that diverges greatly from fundamentals.

And it may turn out that the current pace of yen weakening has gotten way ahead of itself, and that joint intervention could break that momentum—even reverse it somewhat—at least for a while. That would be more likely if Washington supported Tokyo’s move. However, the fact is that the yen’s weakness does reflect economic fundamentals, and, in such cases, intervention only works temporarily.

Consider the last massive intervention: when from January 2003 to March 2004, the MOF spent a gargantuan ¥35 trillion ($320 billion at the 2003 ¥/$ rate), an amount equal to 1.7 times the entire current account surplus over 15 months. The MOF was trying to prevent the yen from strengthening. Yet, at the end of the intervention, the yen was 9% higher than when it betan started. All the MOF accomplished was to enrich currency speculators.

Watch The Interest Rate Gap

The fundamental factor behind the slide of the yen is that the fact the US and most other countries are hiking interest rates to fight inflation, while the BOJ insists that it will not raise rates in Japan. Consequently, bond investors can make more money by shifting money from bonds in Japan to bonds in the US. As they do so, the law of supply and demand sends the yen downward. Currency traders, seeing this, add to the downward pressure.

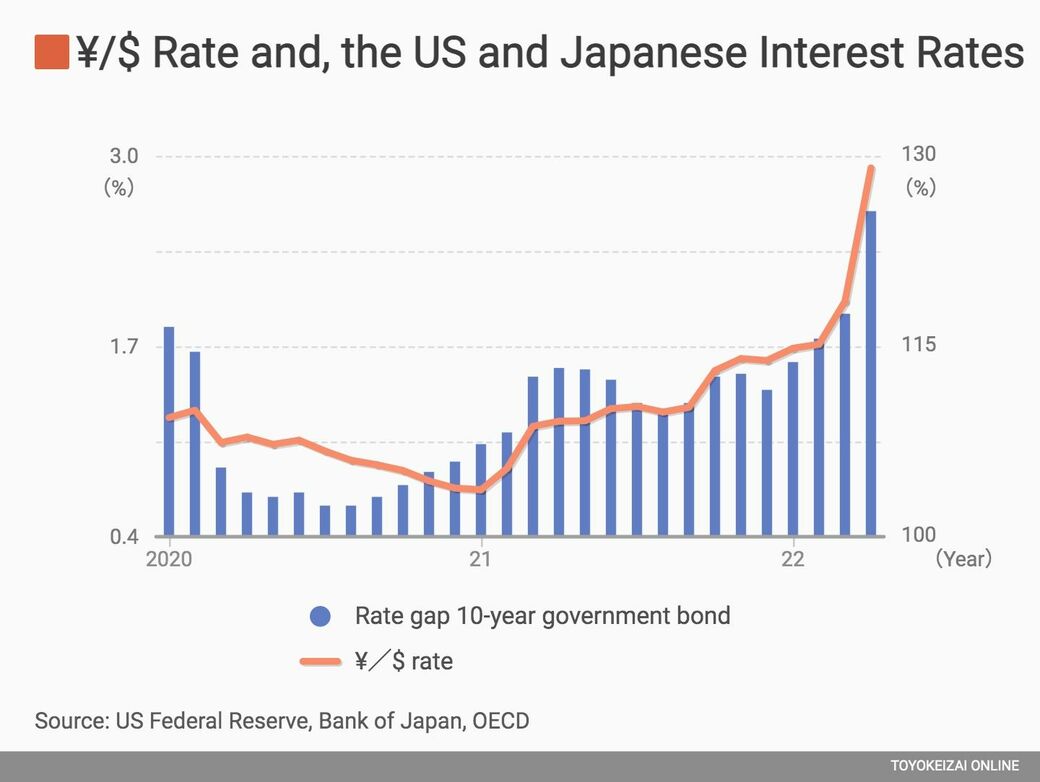

Back in September, when the interest rate on ten-year US Treasury bonds and Japan Government Bonds (JGBs) was just 1.3%, the yen was worth ¥110/$. By April 19, when the interest rate gap widened to 2.6%, the yen plunged to ¥129.

In fact, since the beginning of 2020, there has been an extremely high 84% correlation between the ¥/$ rate and the size of the gap between ten-year US Treasury bonds and ten-year Japan Government Bonds (see figure). Since the US Federal Reserve has said it will raise rates as much as six times this year, investors know the rate gap will get much wider and they are fleeing the yen in anticipation of that.

If Kuroda were to shift his stance on interest rates, that could have some impact, but he insists that he will not. On contrary, he has said that the BOJ will spend unlimited amounts of money to keep the 10-year JGB rate no higher than 0.25%. It’s not just that he feels a weak yen is a good thing; it’s also because he vows not to raise rates until Japan hits 2% inflation on a sustained basis.

A Cheap Yen Doesn’t Boost Exports Like It Used To

A currency rate that is too cheap hurts a country just as much as one that is too strong. At ¥129, the yen is far too weak to be of net benefit to Japan.

The BOJ argues that a weak yen is a net positive for Japan because it because it boosts exports, and the latter adds to demand in the economy. That, in turn, raises production, investment and hiring.

This, claims the BOJ, surpasses the negative impact on real consumer spending from paying higher prices for imports. At some currency rates that is true. In the first four years of Shinzo Abe’s term, markets believed that he was correcting an overly valued yen and that this would boost exports. This belief sent the yen skyward.

Every time the yen dropped a point in value, the Nikkei 225 rose 221 points. But that linkage didn’t last beyond those first four years. In fact, today, the market is having the opposite reaction. From March 30 to April 20, as the yen weakened by 4% so did the Nikkei 225.

What accounts for the difference? Firstly, yen depreciation no longer boosts exports as much as in the past. One reason is that more and more companies are sending their production offshore. Two-thirds of Japanese autos are made overseas these days. A BOJ study shows that industries with more overseas production get less of an export boost for each 1% depreciation of the yen compared to industries with less overseas production.

A second reason is that many Japanese makers of electronics and machinery are no longer as competitive as they used to be, whether they make their products in Japan or overseas. Despite a 40% surge in global electronics sales from 2008 to 2020, every one of the Japan’s top ten electronics hardware manufacturers saw its global sales slump.

Worse yet, total sales of Japanese electronics firms plunged 30%. In the machinery sector (other than autos), Japan’s share of global exports, which had been greater than that of the US and Germany in 1991, had gotten smaller than the US and Germany by 2018. This occurred despite a depreciation of the yen during that period.

As a result, Japanese companies whose reputation for superiority used to enable them to charge a premium price now have to scramble for sales by offering lower prices. But the size of the necessary price cuts has gotten bigger.

When the same BOJ study looked at 2,700 different products, it found that, whenever the yen got weaker during 2002-2010, 86% of the products enjoyed an increase in sales. By 2011-19, the share was down to just 72%. For the other 28%, yen depreciation actually hurt exports because it raised the cost of vital imported inputs like energy and raw materials.

But look a little closer. Does a 10% depreciation of the yen lead to a 20% hike in the number of items sold, or 10%, or just 5%? For most items, the size of the boost was considerably smaller in 2011-19 than ten years earlier. And for the 28% of products where yen depreciation depressed exports, the size of the reduction was worse than ten years earlier.

The upshot is that Japan’s exporters are like someone dependent on painkillers: they need a bigger dose just to get the same benefit, all the while hurting their underlying health.

The Impact, Or Lack Of Such, On Imports

The textbooks tell us that currency depreciation provides another boost to GDP because it raises the price of imported items. As a result, consumers and businesses both switch from buying imported goods to buying the same products from domestic producers. A look at the structure of Japan’s imports shows that this logic does not apply in the Japanese case.

First of all, about 40% of Japan’s imports are items like mineral fuels, food, and raw materials for which there are few, or no, domestic alternatives. Moreover, a country needs just about the same amount of food, oil, or iron ore no matter what the price. The only result of yen deprecation is that Japanese companies and households now have to pay higher prices to foreign producers.

In these products, yen depreciation simply transfers income from Japanese people to foreigners. Paying higher prices for import-intensive food is one reason Japanese families have to spend a larger share of their income on food than at any time since the mid-1980s. This leaves them with less money to spend on other items. A lower share of spending on food is a classic measure of a country’s development.

What about the other 60% of imports? These are mostly manufactured goods, ranging from chemicals to machinery to assorted industrial parts to toys.

As it turns out, 60% of these items are made not by foreign companies, but by the overseas affiliates of Japan’s own companies, e.g., a battery from a Panasonic plant in Thailand or an air conditioner from its factory in Malaysia. Most companies don’t even make the same product in Japan that they now make overseas, at least not the same model.

As a result of these two factors, when the yen depreciates, Japan still buys more or less the same volume of imports; it just pays more for them.

Paying More To Get Less

Suppose you were a dressmaker bartering your products with the local grocery store. Suppose the grocer said he’d give you only half as much food for each dress as before because a new out-of-town dressmaker can do a better job. You might take the deal on the grounds that getting half as much food is better than no food at all. However, you’d still be worse off than you were.

A cheaper yen is like this. Japan is getting less food for each Toyota it exports. That might be good for Toyota, but not for Japan’s consumers. The benefits might still surpass the costs if that led Toyota to export more cars, hire more workers and pay the latter higher wages.

But that’s not what’s happening in today’s Japan. There are always both benefits and costs in any economic transaction. With the yen so weak, the benefits are no longer worth the costs.