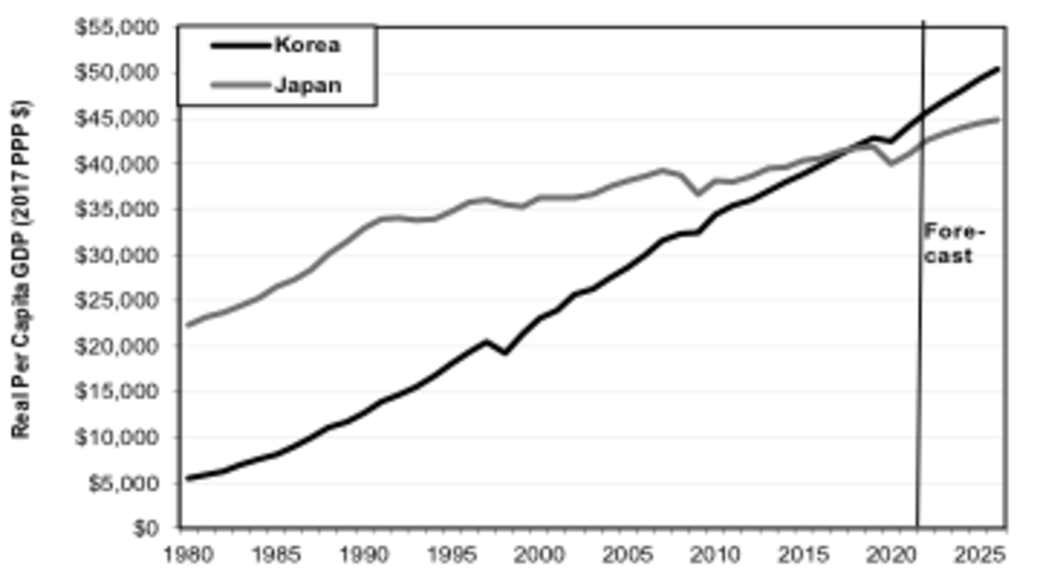

It was headline news when the Japan Center for Economic Research predicted that Korea would surpass Japan in nominal GDP in 2027 and Taiwan do so in 2027. However, according to the International Monetary Fund, in real terms, Korea already passed Japan in 2018 while Taiwan did so in 2009.

By 2026, the IMF projects, Korea will be 12% ahead of Japan.

The IMF uses a standard measure, called Purchasing Power Parity (PPP), which makes adjustments for fluctuations in prices and currency rates so as to compare actual living standards.

Moreover, Korea, unlike Japan, has passed on the fruits of its growth to its workers. For the three decades from 1990 through 2020, the average Japanese worker enjoyed virtually no increase in annual real wages (not including benefits), whereas the pay of Korean workers doubled. Korean workers now enjoy higher real wages than their Japanese counterparts.

This “reversal of fortune” says more about Japan than Korea. Healthy newly-industrializing economies grow faster than the richest economies as they catch up to the technological level of the latter. Japan and Korea enjoyed a faster catch-up than most other countries, and, for a while, catch-up continued in Japan even after the “economic miracle” ended.

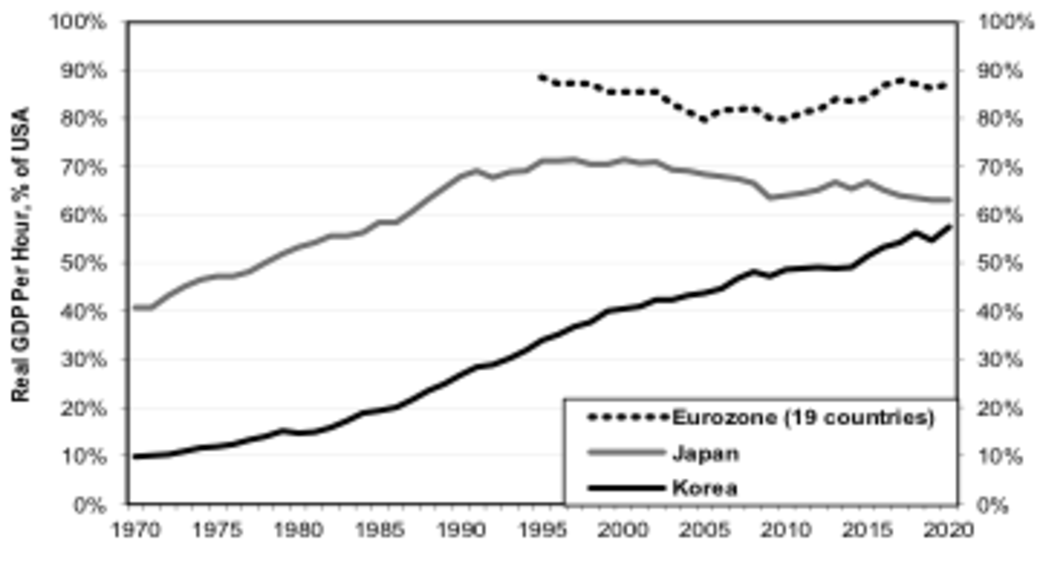

In 1970, each Japanese worker could produce in an hour only 40% as much GDP as his US counterpart. By 1995, that was up to 71%. Then, the lost decades sent Japan into retreat. The ratio is now down to just 63%.

Korea, by contrast, continued its catch-up, soaring from 10% of the American level in 1970 to 58% by 2020. Soon, Korea will pass Japan on this productivity measure as well.

Korea Avoid Japanization

What makes Korea’s achievement particularly illuminating is that it shares many of Japan’s structural defects but has found ways to mitigate them. Like Japan, Korea is a “dual economy,” i.e., a hybrid of extremely efficient exporting sectors and woefully inefficient sectors in parts of domestic manufacturing and most services.

Korea’s productivity gap between small and medium enterprises (SMEs) and large firms is the third-worst in the OECD. Meanwhile, more than a third of its labor force consists of low-paid nonregular workers. The economy is so lopsided that Samsung Electronics alone accounted for an astonishing 20% of all Korean exports in 2019. That’s very risky.

Consequently, in 2015, the Washington-based Korean Economic Institute warned that, without reform, “We only need to look to Japan to see Korea’s likely future.” It added that, in neither country can a few super-competitive export industries indefinitely remain “a large enough engine to power the entire economy.”

In fact, Korea’s per capita growth rate has already declined from 9% per year in the mid-1980s to only 2.5% during 2014-19. To be sure, growth does slow as economies mature, and 2.5% is a lot better than Japan’s 1.1% during the same period. Still, without Korea’s Japan-like structural defects annual growth could be 1-2 percentage points higher, according to the OECD.

Here’s the bottom line: while both countries are still far below per capita GDP in the US and much of Europe, Korea continues to catch up but Japan is falling further behind. Moreover, Korea is doing more to remedy at least some of its defects. These similarities and differences make Korea a good mirror to hold up to Japan.

Getting the Basics Right

For economies to grow well, they need productivity-enhancing practices to give it a high rate of potential growth. At the same time, they need demand-side stability so that the economy operates at full capacity.

Korea has managed the demand side of things far better than Japan. As noted above, workers’ wages have risen in tandem with overall GDP. As a result, households can afford to buy what they make. The economy does not need chronic government deficit spending and an ever-larger trade surplus to make up for shortfalls in private domestic demand.

While Korea’s wage inequality is worse than Japan’s, it has been working on this problem. For example, the minimum wage has been raised to 62% of the median wage, the third highest ratio in the OECD. In Japan, it’s still only 45%.

Because domestic private demand is strong, Korea is far less vulnerable to global shocks, even though Korea’s trade:GDP ratio is twice as Japan’s. During the 2008-09 financial meltdown, Korea’s GDP rose by 4% even as Japan’s fell 7%. During the first two years of COVID, Korea’s GDP rose 3% while Japan’s fell 3.0%. Countries less vulnerable to macroeconomic shocks enjoy faster average growth over the long term.

On the productivity side, the first ingredient for economic takeoff is capital investment in modern equipment. A farmer with a combine, a factory machinist with a numerically-controlled machine tool, or an office worker with a Personal Computer can produce a lot more. Back in 1980, each Korean worker had only 23% as much capital as his Japanese counterpart. By 2020, a Korean worker had 12% more.

The second big requirement is education and training, so that the population can not only handle the world’s latest technology but can invent improvements on their own. Educating non-working women leads to smarter children.

“Human capital” measures how much schooling each person gets and how much additional time in school contributes to growth in each country. In 1960, Korea enjoyed only 70% as much human capital as Japan. By 2019, it had 5% more. Korea came in 5th among 31 rich countries while Japan came in 13th.

How can Japan lag so much when so many Japanese graduate from college? Among 24-34 year-olds in 2020, Korea came in first with 70% of that age group having graduated and Japan came in third at 62%. What that tells us is that Japanese companies have not organized work or deployed technology in ways that best exploit that education.

Non-regular workers, for example, are given little of the on-the-job training that regular workers have long enjoyed, a practice crucial to worker productivity. Spending by Japanese companies on off-the-job training has dropped 40% since 1991. On-the-job training costs are not counted separately from overall personnel costs, but have almost certainly dropped due to the rising share of non-regulars.

The Korea-Japan gap in human capital seems likely to grow, and not just because of the decrease in training. Out of 26 OECD countries, Japan spent the second-lowest in public money as a share of GDP on pre-college education. Korea came in 15th.

When it comes to university education, Japan spent the least in public money. The financial burden is placed on families. As a result, too many bright Japanese students from less affluent families don’t get to go to college—a loss for both the individual and for Japan. In 2010, Korea was 4 percentage points ahead of Japan in college graduation rates in this age group. By 2020, it was 8 points ahead.

Investing A Lot Vs. Investing Wisely

In going from poverty to prosperity, the name of the game is how much a country invests in infrastructure, modern industries, and education. But, once a country hits a certain level of economic maturity, what matters more is not how much a country invests but how wisely, i.e., how much companies gains from each yen or won invested.

Samsung has left SONY in the dust, not from having better machinery or smarter workers, but from superior strategy and execution.

The measure of how much benefit a country gains from both physical and human capital is called Total Factor Productivity (TFP). If inputs of capital and labor grow 2% and output of GDP grows 3%, that 1 percentage point difference is TFP. In the long run, solid growth in TFP is the best assurance of growth in per capita GDP.

During 2014-2019, Korea came in first among 23 OECD countries, with TFP boosting growth by 1.5% a year. Japan, by contrast, was just 10th at 0.6%.

Korea vs. Japan on Digital Technologies

Some of TFP growth comes just from investing in more modern technology, e.g., steel mills with electric arc furnaces. But all rich countries have access to the same technology. So, one of main reasons rich countries differ in TFP growth is how well they use that technology. Consider digital technologies.

Both Korea and Japan suffer from a big digital divide between the corporate giants and the SMEs. Still, those Korean companies who do invest in Information and Communications Technology (ICT) have done better job in exploiting its possibilities.

For example, do companies use ICT just to cut costs of tasks they are already performing, like automating clerical and factory work, or do they use it to produce new or improved products, or to target customers better? The Institute for Management Development ranks countries on that sort of “business agility” in the digital area. Out of 64 countries in 2021, Korea came in 5th whereas Japan lagged at a dismal 53rd.

Companies cannot make the most of ICT unless their employees have the skills to use it well. When the World Economic Forum ranked 141 countries according to the digital skills of its labor force, Korea came in 25th but Japan a surprisingly low 58th.

Entrepreneurship

Both countries talk about encouraging more entrepreneurship and helping SMEs grow. Korea, however, is turning more of its rhetoric into action. Investing in R&D makes a big difference in how many high-growth SMEs a country gives birth to.

In Japan, only 12% of government financial aid to R&D goes to companies with less than 250 employees, the least in the OECD. In Korea, half goes to those SMEs. That’s one reason that 22% of all Korean business R&D is conducted by SMEs, more than either the US or France. In Japan, it’s just 4%.

As a result of a number of policies along the same line, in 2017, Korea had more than 8,000 high-growth enterprises (HGEs), i.e., companies with at least 10 employees that grew at least 20% a year for three years in a row.

Among 12 rich countries, Korea came in 5th in the number of HGEs per million workers. Unfortunately, Japan has never measured this vital indicator of entrepreneurial success. If a country measures what it considers important, this lapse is telling.

Globalization

Countries enjoy faster productivity growth if they have higher ratios to GDP of international trade and inward Foreign Direct Investment (FDI). Such globalization helps growth partly due to transfers of technology and partly due to the force of competition.

Korea’s exports and imports are each about a third of GDP, twice as high Japan’s ratios. The cumulative stock of inward FDI is 16% of GDP in Korea; it’s just 5% in Japan.

There is lots of good news in what may appear to be a bad news story for Japan. Korea’s experience shows that, if Japan implements the right structural reforms, it too can have a bright future.