For someone with an injured leg, a crutch is necessary, but relying on it for too long just atrophies the muscles. So it is with Japan and the weak yen. Ever since early 2013, when Shinzo Abe and Haruhiko Kuroda ascended to the Prime Ministership and Bank of Japan Governor’s post, respectively, Tokyo has worked to push down the yen.

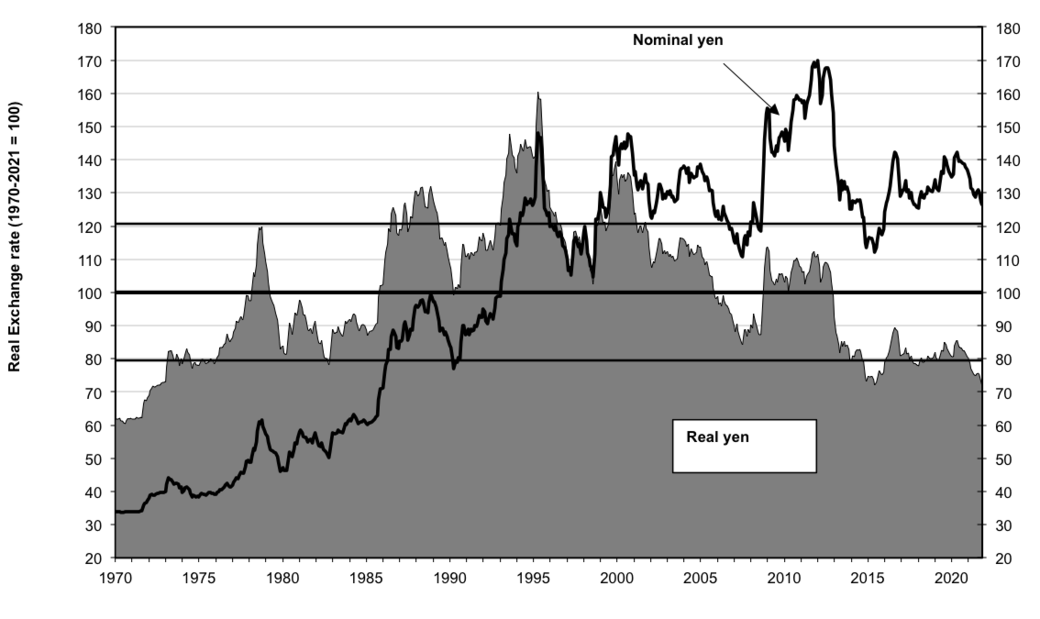

Today, in “real” terms, the yen is now at its lowest level in a half-century, almost a third below its long-term average (Figure 1). (“Real” means adjusting for different rates of inflation in Japan and its trading partners.)

Today, with the yen widely predicted to weaken even further, a disagreement has emerged between the BOJ and the new Kishida administration on whether that’s a good thing. Kuroda insists that a weak yen is a “net positive” for Japan, even though he admits that, “the yen's depreciation might have an increasing negative impact on household income through price rises,” for import-intensive items like food, energy, clothing, and footwear.

In a January 18 press conference, Kuroda even argued that there is “no such thing as a weak yen.” By contrast, on January 7, Finance Minister Shunichi Suzuki stressed the need for “currency stability,” a “verbal intervention” telling the markets that the yen had dropped too fast and too far.

The Weak Yen and GDP Growth

If your only concern is GDP numbers or if you see moderate inflation as beneficial, no matter what its cause, then it might look as if Kuroda were right. Just like a patient with atrophied muscles is even more in need of that crutch. However, just as the patient really needs physical therapy to wean it from the crutch, Japan needs economic reform.

A weak yen reflects a lack of strength at home and diminished competitiveness overseas. As will be detailed below, Korea has been able to grow faster than Japan even though the Korean won strengthened.

Domestic demand has been so weak during Abe-Kuroda years that even the little growth Japan has eked out has been excessively dependent on government spending and a rise in net exports (i.e., exports minus imports).

The economy required artificial stimulus because real (price-adjusted) household income had been depressed by two tax hikes and stiff price hikes in import-intensive items. As a result, personal consumption actually fell by 1% during that seven-year period, a lengthy decline unprecedented in the postwar era.

A weak yen enables exporters to lower their prices in foreign markets and therefore boosts exports. Suppose Toyota can make a profit by selling a car for ¥2 million and that ¥100 is worth $1. The car will sell overseas for $20,000. If the yen’s value is pushed down to ¥120/$1, Toyota could lower the overseas price to $16,667, still take in ¥2 million per car, and sell a lot more of them.

As the yen plunged, trade took the lead in driving GDP growth. From first quarter of 2014 to the last quarter of 2019 (before COVID), Japan’s GDP expanded just ¥7.2 trillion (a measly 0.2% annual rate). However, net exports grew even more: by ¥10.7 trillion yen. In other words, without external demand, GDP would have fallen during that period.

That’s why Kuroda says a weak yen is a net positive. This, however, is not a sustainable strategy. Japan’s trade balance is such a tiny portion of GDP that it cannot continue supplying all the growth. Moreover, it’s very risky because it makes Japan very vulnerable to shocks elsewhere in the world, like the 2008-09 financial catastrophe and COVID.

Korea vs. Japan

A country that needs a weak currency to sell its exports is like a firm that can only sell its products if it keeps cutting prices by lowering the wages of its workers. A healthy economy is like a firm that can sell its products at good prices while raising the wages of its employees. Productivity growth, not a weak currency, is the key to a growth strategy that lifts living standards. That is the difference between Japan and Korea.

Today, the real value of the yen is 29% below its 2012 level. By contrast, the real Korean won is 7% above its 2012 level. Nonetheless, Korea’s economy has shown superior performance. From 2007, just before the global economic catastrophe, to 2019, just before COVID, Japan’s per capita GDP grew just 7%; Korea’s grew five times as much: 35%. Moreover, while Korea’s per capita GDP was 20% below that of Japan in 2007, it surpassed Japan in 2019, and its lead is growing.

Domestic demand fueled Korean growth. While exports grew at a rapid clip, so did imports. As a result, the biggest contributors to GDP growth were household consumption and business investment. Make no mistake: Korea is far more open to trade than Japan. Total trade (exports plus imports) amounts to 78% of GDP in Korea vs. 37% in Japan.

That boosts Korean growth because it improves productivity, i.e., output per worker. However, Korea does not need an ever-rising trade surplus (exports minus imports) to make up for shortfalls in domestic demand.

Consequently, unlike Japan, Korea is not tossed in the wind by the ups and downs of external events like the 2008-09 financial maelstrom or COVID. In 2020, COVID caused Japan’s GDP to plunge 4.6% even though Japan had few cases compared to other countries. Korean GDP, by contrast, fell just 0.9%. Moreover, Japan is having a much slower recovery. The IMF projects that, in 2023, Japan’s GDP will be only 0.2% above its 2019 level whereas Korea’s will be up 6%.

The most important difference is that Japan relies on a low wage/weak currency strategy to fuel its exports while Korea’s exports are fueled by efficiency improvements and innovative products, i.e., a strong currency/high wage strategy.

Over the period from 2005 to 2019, output per worker in Japanese manufacturing grew 25%, but workers were denied the fruits of that, with compensation (wages plus benefits) up a negligible 1%. By contrast, in Korea during the same period, factory productivity grew 57% and workers enjoyed a 52% hike in earnings.

As a result, while in 2005 Korean workers’ annual wages in all industries, not just manufacturing, were 12% below those in Japan, by 2020, they were 9% higher. (This change is not caused by the rise of low-paid non-regulars in Japan since Korea has the same syndrome.)

Competitiveness without improvement in living standards is not real competitiveness.

The Weak Yen Produces Harmful Inflation

Abe and Kuroda came to office convinced that reaching 2% inflation would be a panacea, and it would take Kuroda only two years to achieve that target. He never came close. Worse yet, most of the inflation that the BOJ did achieve was the result of the weak yen and the two consumption tax hikes.

Had Abenomics generated inflation via domestic economic strength, that would have been beneficial. But elevating headline inflation numbers via higher import prices causes more harm than good.

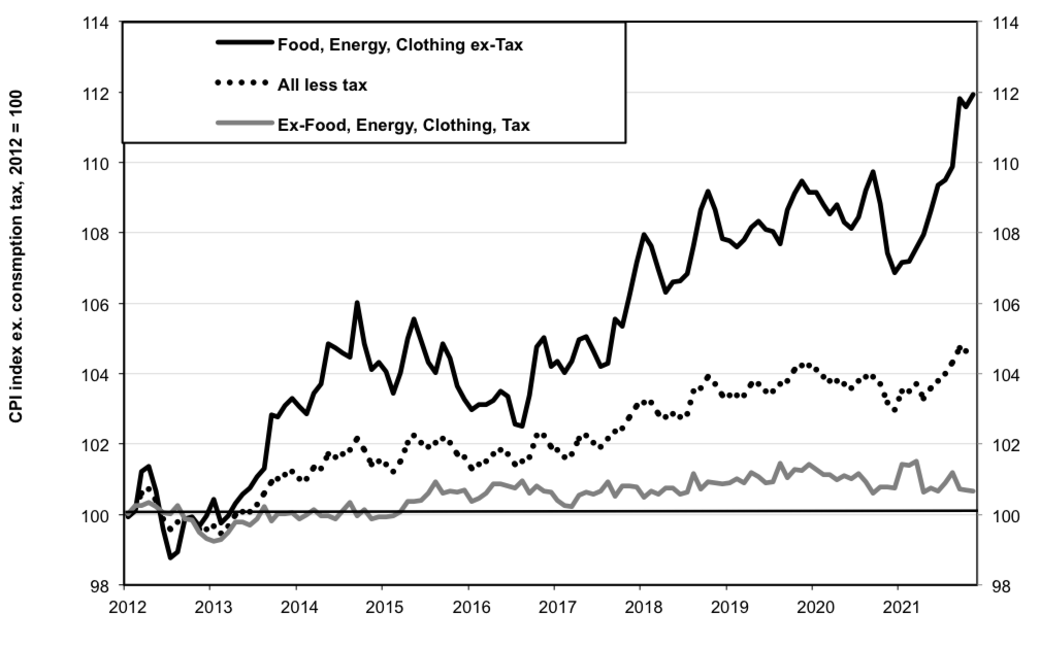

Just as a weak yen lowers the price of Japan’s exports, it raises the price of imports. Nearly 40% of consumer spending is accounted for by items dominated by imports, including energy, clothing, and footwear and food (by calories, 60% of Japan’s food is imported). Not counting the consumption tax hikes, the price of those items went up by 12% from 2012 to 2021.

By contrast, prices for the other 60% of consumer spending rose by a negligible 0.7% in the same period. The bottom line is that more than 90% of the entire rise in the consumer price index ex-tax was driven by import-heavy items (see figure 2).

The rise in imports prices harms Japan just like Japan is hurt when OPEC pushes upward the price of crude oil upward. But that’s just part of the story. While the weak yen hurts Japanese households, the country’s big multinational companies get richer. Consequently, the weak yen indirectly transfers income from the Japanese consumer to those big companies.

This would be less of a problem if those companies turned around and shared that bonus with their workers. But they have not. Among Japan’s 5,000 biggest firms, current profits have soared by ¥19.8 trillion ($172 billion) since 2012, but payments to workers were upped only ¥2.7 trillion ($23.5 billion). The Kishida administration is correct when it says that the “trickle down” theory of Abenomics produced very little actual trickle down. Unfortunately, so far it doesn’t look as if Kishida will follow words with action.

Whither the Yen?

Many currency forecasters expect the yen to weaken even further now that central banks in North America and Europe are raising interest rates, but the BOJ is keeping rates low. This increases the gap between what bondholders can earn elsewhere compared to Japan. As that happens, many investors shift money from Japan to other markets. Over the past year, the expansion of the interest rate gap was a pivotal factor in weakening the yen from ¥104/$ to ¥115.

However, currency forecasts are often wrong. Sometimes, the interest rate gap plays a very strong role in the yen’s ups and downs. At other times, it is outweighed by other factors.

During the dozen years from 2001 to 2013, a statistical regression shows that the interest rate gap accounted for 80% of the ups and downs in the yen’s value. During 2014-19, however, the rate gap played virtually no role. Since 2020, the gap seems to have become important again, but that is too short a time to estimate the power of the linkage during the coming year or two.

One thing is clear. To the extent that the rate gap plays a big role, the BOJ will have to watch from the sidelines. The 10-year JGB rate is already so low, just 0.16%, that the BOJ doesn’t have room to push it down much further. What really matters is what the American and European central banks do and how the market responds to those movements.

Abenomics has weakened not just the yen, but Japan’s control over its own economic destiny.