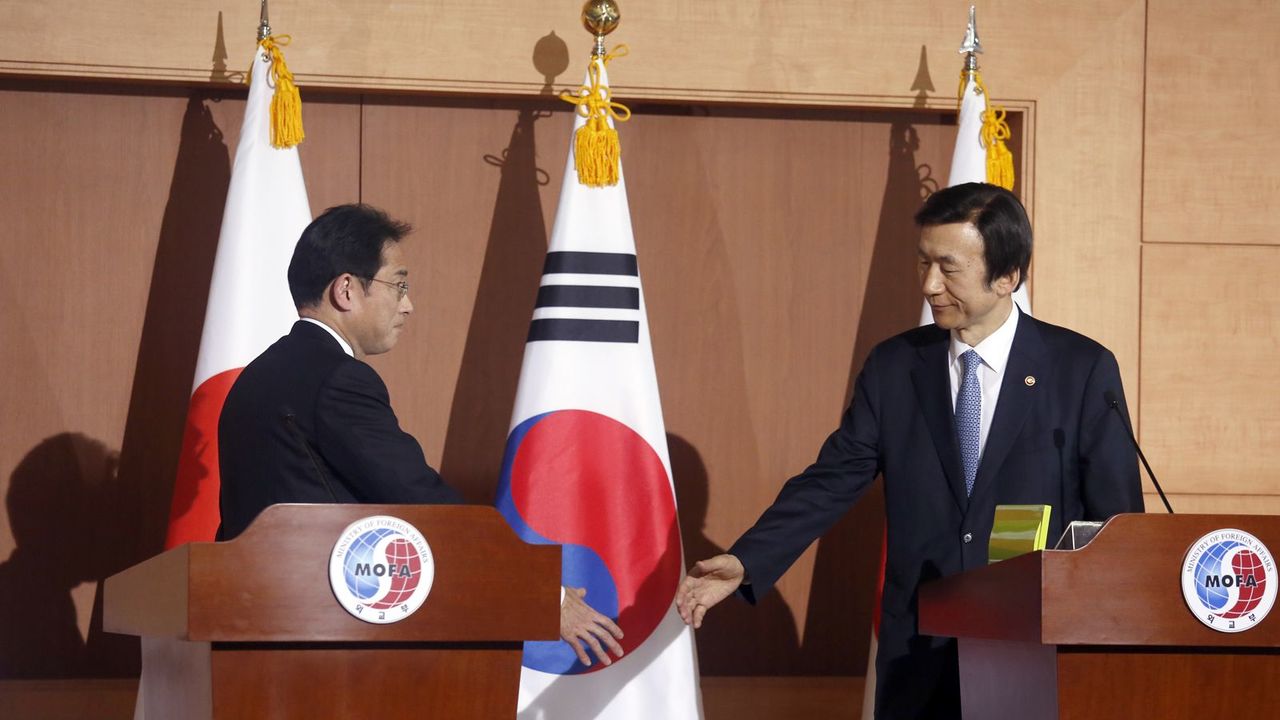

The breakthrough agreement on the comfort women issue, issued by Japan and South Korea on December 28th, was a delicate compromise. By its nature, the deal is fragile, facing opposition in both countries that could escalate if either government backs away from the agreement.

Behind this agreement, however, there is a foundation of at least four years of on and off negotiations between the two governments, negotiations that crashed and stalled many times. Success came only after the two leaders, South Korean President Park Geun-hye and Japanese Prime Minister Shinzo Abe, cleared the way for compromise. “The two leaders wanted it and negotiated hard and in a very serious manner,” a senior U.S. official told me.

While giving due credit to the political leadership, this agreement could not have been reached without the persistent pressure of the Obama administration. President Obama delivered some of that pressure in very public fashion. American officials resisted a mediating role, worried that the U.S. would be blamed for the outcome.

But quietly American officials were engaged down to a very detailed level of the disputes over specific language in the agreement, careful not to intervene too much but also clearly communicating to both sides the American insistence that a breakthrough was possible with compromise.

The U.S. role flowed from the perception, deepened in the last few years, that the dysfunctional relationship between South Korea and Japan threatened to undermine American strategic interests. The frozen ties at the highest level between the two principal American allies in Northeast Asia weakened the defense of the Korean peninsula against an unstable North Korean regime and aided China’s bid for regional dominance.

The origins of this agreement actually go back to the previous government of the Democratic Party of Japan, which came into office seeking to improve relations with its Asian neighbors and ready to recognize Japan’s responsibility for wartime crimes. Then Prime Minister Naoto Kan took a significant step in 2010, marking the 100th anniversary of the Japanese annexation of Korea by issuing an apology for colonial rule.

South Korean President Lee Myung-bak, a former businessman, was eager to move ahead to improve ties with Japan. On August 30, 2011, however, the Constitutional Court of Korea ruled that the government’s failure to find a solution with Japan to compensate the surviving “comfort women” was a violation of the Constitution.

Following that, officials from the two foreign ministries began discussions to find a formula that would go beyond the Asian Women’s Fund formed in the 1990s, which was rejected by many of the victims and by Korean civil society activists because Japan did not take responsibility for its historical act and compensation payments were made from private contributions rather than official funds.

The officials discussed a new agreement that included a letter of apology from the Japanese Prime Minister to the victims and humanitarian payments out of the official budget, though not as formal reparations (the Japanese insisted, and continue to do so, that they had settled all such claims with the San Francisco peace treaty and the 1965 treaty to normalize relations with Korea).

In the meantime, however, the Japanese premiership changed hands in September, with the more conservative minded Yoshihiko Noda taking over. Noda, the son of an army paratrooper, personally shared the historical revisionism of Japanese rightwing conservatives such as Abe, supporting visits to Yasukuni shrine and opposing the Kono statement acknowledging the Imperial Army’s official role in coercing women to provide sexual services.

Noda and Lee met at a summit meeting in Kyoto on December 18th. One week earlier Korean activists had erected a controversial statue memorializing the comfort women across the street from the Japanese Embassy in Seoul.

There are two differing accounts of what happened. In the Japanese version, Noda was prepared to discuss economic and security issues but was surprised when Lee insisted on dealing with the comfort women issue.

A senior Korean official who was present at the meeting told me they expected Noda to sign off on the basic formula negotiated by the two foreign ministries. Instead, he said, Lee was surprised when an angry Noda spent the opening dinner demanding that the statue be removed and stating there was no need for a new apology. That battle continued into the next day of talks.

Both sides made a stab at reviving the negotiation the following spring. Under the direction of then Vice Foreign Minister Kenichiro Sasae, the Japanese offered a package of a letter from the prime minister, a face-to-face apology by the Japanese ambassador to Korea and humanitarian aid, but without accepting official responsibility. By then, however, the breakdown in trust was too much to overcome. It would be almost four years until the leaders of South Korea and Japan would meet again in a bilateral summit.

Park and Abe both came into office deeply wary of each other. Park was personally determined to settle the comfort women issue, arguing it must be done before the remaining aged women, then numbering only in the 50s, passed away. Relations deteriorated rapidly however after Abe signaled his intention to reverse the official Japanese government stance on the war, not least to deny any official role in the coercion of the women.

American pressure

American officials began to become increasingly concerned by the rupture in relations, particularly in light of China’s growing military assertiveness. In November 2013 the Chinese alarmed Washington by declaring the establishment of an air defense zone in the East China Sea that overlapped both Japanese and Korean territory. Vice President Joe Biden made a swing in December through Tokyo, Beijing and Seoul, dominated by this issue.

Thinking he had secured a promise from Abe not to take provocative steps on history issues, Biden pressed Park to agree to a summit with Abe. Shortly after Biden’s visit, I met with Park as part of Stanford group and we found her clearly unhappy with the American pressure, expressing concern that Abe could not be trusted. Her resistance was vindicated only days later when Abe shocked Biden by visiting Yasukuni shrine, prompting an unusual public slap on the wrist issued by the U.S. Embassy in Tokyo.

This triggered some serious debate within the U.S. government about the efficacy of getting involved in the disputes on history between Korea and Japan. While still rejecting a mediating role, American pressure on both Tokyo and Seoul became more visible, led by the President.

In March 2014 Obama organized a trilateral meeting on the sidelines of the nuclear security summit in The Hague, focused on North Korea. Obama tackled the history issues more directly during a trip the next month to both capitals. He was careful in Japan to avoid pressing Abe in public but in Seoul, Obama went beyond Secretary of State Hillary Clinton’s use of term “sexual slavery” to directly address the issue of Japanese responsibility for “a terrible, egregious violation of human rights.” He called for a clear account of the past and joint efforts to resolve the issue.

In the year and half that followed, the Korean and Japanese foreign ministry officials met 12 times but little progress was made, indicating an absence of political will at the top. The Americans pressed their case quietly and privately.

“The US State Department as well as White House played a pivotal role to move PM Abe this time,” a senior Korean source involved in managing relations with Japan told me. “And the U.S. side made it no secret to the Korean side whenever high-ranking officials from Seoul visited Washington.”

Prime Minister Abe certainly heard the American message, as evidenced by his decision during his 2015 visit to Washington to clearly state his commitment not to reverse the Kono statement, and by the effort to avoid provocation in the wording of the August statement on the 70th anniversary of the end of the war.

Park visited Washington in mid-October and found American policy makers echoing Japanese accusations that South Korea was leaning toward Beijing. Within Korean government and policy making circles there were calls for the President to abandon her insistence on a comfort women deal as a precondition for a summit and to adopt a “two track” approach to relations with Japan, separating history issues from security issues.

She shifted her stance and met with Abe in early November, on the sidelines of the trilateral summit with the Chinese, where both leaders committed to try to conclude an agreement by the end of the year, the anniversary of the normalization of relations.

The wind of change

The December deal follows the outlines of the framework first discussed four years ago but with some key changes. The Japanese accepted the use of the word ‘responsibility’ and admitted official involvement in the brothel system. The foundation was a new idea, offering a convenient way around defining the payments as compensation.

Tokyo, on Abe’s insistence, got a commitment to the idea of a ‘final and irreversible’ settlement, though that goes both ways. And most ambiguously, the Koreans agreed to try to move the statue, though only with the consent of the civic groups.

American officials give credit for the deal to the two governments and their leaders. But in a background briefing for reporters, a senior U.S. official could not resist a clear hint at a more active U.S. role:

“The U.S. has played an appropriate and constructive role. The Obama Administration strongly supported all gestures of reconciliation. We have shared our best advice; we've underscored the benefits to us and to everybody in reaching an agreement; and we've worked quietly to, where possible, prevent or to resolve misunderstandings between the two.”

The danger of the agreement falling apart is very much on the minds of officials in both Washington and Seoul, and hopefully Tokyo. Abe and Park will both be in Washington next March for another nuclear security summit and a trilateral meeting may be on the agenda. Abe is eager to demonstrate his claim to leadership in Northeast Asia, and Park is facing tremendous challenges at home and from North Korea.

“We need to build off of this to keep the momentum going,” the senior U.S. official told me. “But the good news is that there’s a good deal in the agreement for both of them and it will keep both of them in the game.”