When the members of a business mission to Japan organized by the government of Shanghai visited Japan in March, one member insisted on going to Kyoto. His purpose was not to see temples and shrines in the oldest city in Japan—he wanted to visit companies based there. “Kyoto is the Silicon Valley of Japan, and we want to learn the secrets behind the success of companies there,” said this mission member, who asked not to be identified.

Indeed, in addition to Kyoto’s fame as the sightseeing capital of Japan, the city is also home to a Silicon Valley–style concentration of product makers.

Take the iPhone 6. It offers 3D Touch as its prominent new feature, wherein the LCD screen detects how firmly the user presses the display and provides real-time feedback via subtle vibrations. It appears that Kyoto-based Nidec Corporation is the exclusive supplier of the ultracompact motor used to make those vibrations. This high-value-added motor serves as an important source of future growth and revenue for the company, whose business traditionally centers on hard disk drive products, which are key components in numerous devices.

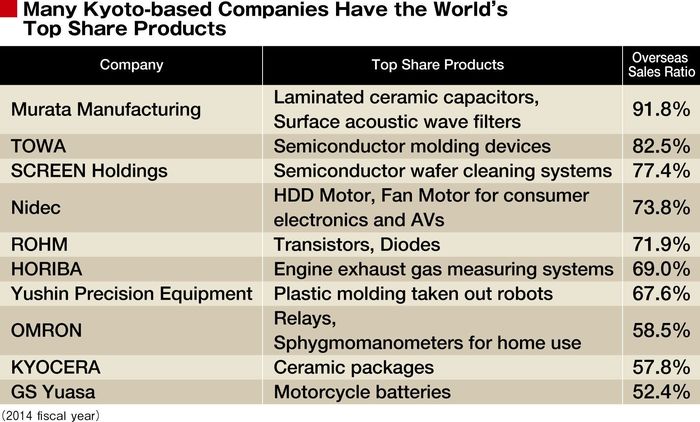

In addition to Nidec, Murata Manufacturing, which makes multilayer capacitors; ceramic semiconductor package producer Kyocera; and other Kyoto corporations make products boasting world-leading market shares.

Their success is not limited to high market shares alone, as 27 of the 29 Kyoto companies listed in the First Section of the Tokyo Stock Exchange are rated at above-average levels (based on ratings for all 862 companies listed in the First Section) in terms of profitability, soundness, or both. Furthermore, when an index of these companies’ market capitalizations is examined, they come in above the market index for the First Section as a whole.

So, what are the secrets of Kyoto-based companies? There are five factors that we believe underpin the strength of these companies:

Factor 1: Close Local Ties and Exchanges

At Nidec’s general meeting of shareholders in June, Chairman and CEO Shigenobu Nagamori stated, “I have great respect for [Tateishi Electric Manufacturing founder] Kazuma Tateishi. He really helped me out for a decade or so following our company’s founding.”

One year after Nidec’s founding in 1974, the company accepted 5 million yen in venture capital funding raised through a joint investment undertaking by the Tateishi Electric Manufacturing Company (now Omron), Wacoal Holdings, and other local companies, fostering Nagamori’s trust in Kyoto’s financial community.

Kazuma Tateishi, who became president of the above-mentioned investment company, provided the support necessary to bring various corporations into this investment venture. Tateishi also offered advice to Nagamori whenever the latter was faced with a worrisome management issue.

Deep ties of friendship between managers, executives, and other top players are a distinctive characteristic of the Kyoto corporate climate. The city center Gion district was once home to the members-only club “Eleven,” an organization proposed by Wacoal founder Koichi Tsukamoto and operated jointly by Tsukamoto and Kazuo Inamori, who is an honorary chairperson at Kyocera.

The club was closed down after Tsukamoto’s death, but several other similar venues for exchange between managers and other higher-ups were created to carry on the tradition, and they still operate in Kyoto today.

“Kyoto companies are unique in that we have no regrets about sharing knowledge with others when they come to a dead end in technology-development efforts,” says Chairman and CEO Kunio Nambu of NABEL, a company that manufactures fully automated egg grading and packing equipment.

His company transitioned to domestic production of this equipment for the first time in the 1970s and owns approximately 120 relevant patents. The source of such technological development prowess is rooted in knowledge sharing between corporations in Kyoto.

Factor 2: Risking the Path Less Traveled

Kyoto companies do their best to avoid entering fields already occupied by other companies, instead exhibiting a pronounced tendency toward the creation of singular products in niche fields.

The unlisted enterprise Ishida, for example, accounts for a 70% market share of certain measurement devices used on food production lines, and Kataoka Corporation controls half of the market for laser welding equipment used in the production of lithium-ion batteries.

But why put aside considerations of scale and size and dedicate oneself to pursuit in specialized fields instead?

Murata Manufacturing provides a good example. When he was young, founder Akira Murata told his father, who ran a ceramic ware shop, that “we have no future with such small-scale sales efforts, so let’s increase our client base.” But his father had this to say: “The only way to increase orders is to approach the clients of other ceramics merchants and offer lower prices. That would end up pushing down profits for both us and others in our industry.”

His father’s business approach encouraged him to pursue new fields instead, and the Murata Manufacturing founder went into special ceramics, a move that eventually led to the company’s production of ceramic capacitors. In Kyoto, a tight-knit community where everybody knew everybody, it became common wisdom to avoid competition so that everyone could live in harmony

Factor 3: Skipping Over Tokyo and Going Directly to the Global Market

Nidec has suffered some humiliating experiences in Tokyo. During the company’s early days, they went to the capital in an attempt to sell their products to major electrical machinery manufacturers. In response, those companies showered them with questions such as “How many employees does your company have?” and “What’s your capital base?” which had nothing to do with the business at hand.

At one point, Nidec’s Nagamori personally traveled to Tokyo and visited the 3M Company, a major player in the global tape recorder industry at the time. Even though Nagamori showed up without an appointment, the members of 3M listened to what he had to say, and in the end, they were pleased with the prices he offered and signed a large-scale contract for Nidec products.

Companies in Kyoto feel that their city, which served as Japan’s capital for more than 1,000 years, holds a higher status than that of Tokyo, which became the nation’s capital just 150 years ago. With roots in this local pride, Kyoto companies have a tendency to skip over Tokyo completely and aim directly for the global market.

Factor 4: Having Nobody to Rely On but Oneself

If an abundance of reserve funds are available, a company can continue investments toward recovery if their products and services perform poorly for a time. Kyoto’s Nintendo Co. Ltd. is the perfect example of this golden rule.

The late Satoru Iwata, Nintendo’s former president and CEO, who passed away this summer, became famous through his ultra-successful Nintendo DS and Wii products; however, the company’s sales have plunged rapidly in recent years as smartphones steal away their customers.

In response to an employee cutback proposal made by an investor at one of the annual shareholders’ meetings, Iwata flatly refused, retorting, “Do you really think that employees in constant fear of losing their jobs will be able to make games that truly impress Nintendo’s customers?” The reason Nintendo has been able to maintain personnel numbers despite its recently dismal performance is the company's remarkably sound financial constitution, as exemplified by their 915.2 billion yen in net cash and 86.2% capital-to-asset ratio.

Many Kyoto companies are rich in case. In addition to adopting niche-focused high-earning business models that lead to natural profit growth, they consciously cultivate robust financial foundations. In a city without large corporations, looking after oneself was the only choice available to local companies. These organizations developed resilience during a hard era in which all they had to rely on was their own resourcefulness and the money on hand.

Factor 5: Positive Cycles That Foster Future Generations

Among the numerous new companies popping up in Kyoto during Japan’s postwar period of high economic growth, early corporations served as incubators of sorts for their management staff. However, Hirokazu Toyoda, secretary general of the Kyoto Association of Corporate Executives, warns that “Kyoto faces a dire crisis” today, pointing out that very few new listed companies have appeared for some time.

In 2012, the rate of new companies founded in Kyoto was 1.78%, falling behind that in Fukuoka and other such cities. The real question now is whether or not Kyoto can achieve positive cycles—top-notch corporate groups giving birth to even better companies—to power the next generation of local corporations.