There were two big losers in Sunday’s Upper House elections.

The biggest loser was the Liberal Democratic Party (LDP), which, together with its Komeito ally, lost its majority in the Upper House (UH) months after having lost its majority in the Lower House (LH) in October. Although 4.5 million more people voted than in the 2022 UH election, the LDP got 5.4 million fewer votes. At 21%, its vote share was the lowest in its 70-year history.

The second loser was the largest opposition party, the left-of-center Constitutional Democratic (CDP). It failed to increase its UH delegation by even a single seat, remaining at 38. By contrast, the right-of-center Democratic Party for the People (DPP) increased its UH seats from five to 22, and the new Trumpian party, Sanseito, multiplied its seats from one to 15. The CDP’s share of the Proportional Representation (PR) segment of the vote (just 12.50%) lagged a tiny bit behind that of both the DPP (12.88%) and the Sanseito (12.55%).

The question is why.

The Role of Inflation in the LDP's Loss

Were rapidly-rising food prices—including a doubling of rice prices over the past year—the reason for the LDP's loss? Or was inflation merely the straw that broke the camel’s back? I would argue for the latter.

This election was about voter confidence in a party’s ability to solve people’s problems. Voters felt that the LDP failed to offer a solution, not just to inflation, but to the myriad economic maladies from which they’ve suffered over the last three decades.

This is not to underplay the political salience of high prices. In last year’s elections around the world, inflation caused every incumbent party in affluent countries, whether liberal or conservative, to suffer a drop in their vote share. A large number were tossed out of power altogether. Never before, in 120 years of record-keeping, has this happened. Japan’s loss of its majority in October’s LH election was a prime example. In an NHK poll ahead of this Sunday’s election, 48% of respondents cited “high prices/the economy” as their number one issue. Coming in a distant second at 18% was “pensions/social security.” Trailing at seventh (7%) was “policies on foreign residents.”

Nonetheless, I’d argue that inflation brought things to a head because it embodied underlying discontent with the long stagnation—or, for millions, even fall—of living standards. (Parallel syndromes exist elsewhere, as shown by the widespread rise of right-wing populist parties.) In 2024, 67% of respondents stated that they are not satisfied with the way democracy is working in Japan, up from 50% in 2017. Additionally, 56% reported not feeling close to any party.

As often happens in Japan, it was a case of “money politics” scandals afflicting the LDP that turned enervating sullenness into energizing outrage, beginning with last year’s elections. Yet, the LDP blinded itself to the profound discontent. In January, I asked an LDP leader: Did the LDP lose simply because of the fundraising scandals, or were voters sending a deeper message about your policies? His answer was: “There is no message, no discontent with our basic policies. It’s only the scandals. That sort of ‘protest vote’ will be temporary, as it has been in the past.” In fact, he and his colleagues were supremely confident that the LDP would easily win the Upper House election. So, no need for introspection or course correction.

The numbers were on the LDP's side. Half of the Upper House’s 248 seats were at stake in this year’s race. The LDP and its Komeito partner entered the race with 66 seats being contested and needed to win just 50 to keep a 125-seat UH majority. Only in a “wave” election would they fail. But a wave election was what took place. Turnout rose to 58%, the highest level since 2010, and the LDP-Komeito coalition kept just 47 seats.

I suspect the LDP will blind itself yet again. They will blame the loss on Prime Minister Shigeru Ishiba, or food prices, or the defection of rightwing LDP supporters to Sanseito. The heirs of Shinzo Abe, led by Sanei Takaichi, are demanding Ishiba’s resignation while offering nothing more than a rehash of Abe’s ineffective monetary and fiscal policies, without even the pretense of a “third arrow.”

Prices Rise While Wages Lag

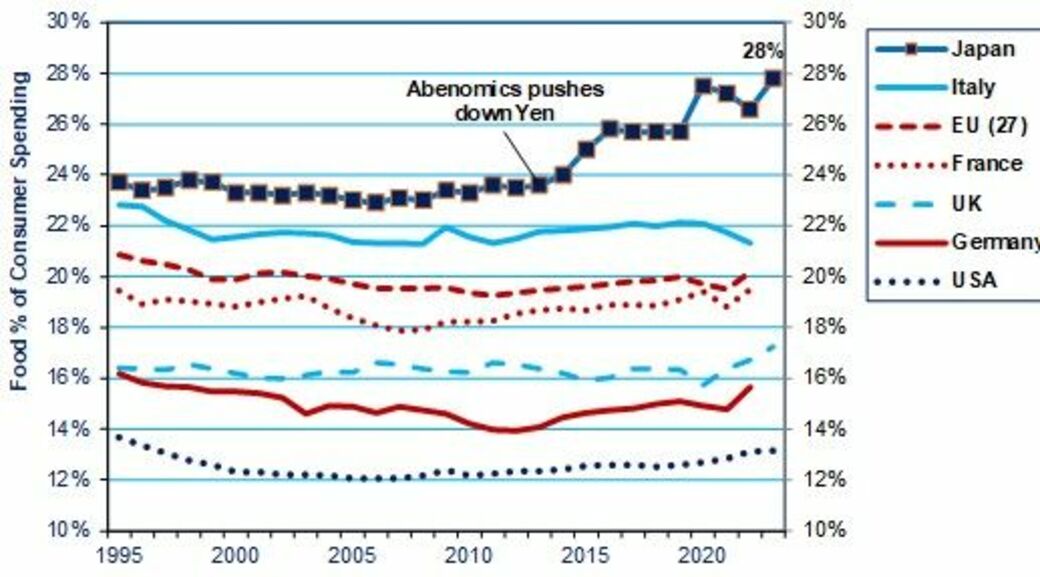

While inflation is just the tip of the iceberg, it is seriously hurting living standards. Food prices in Japan have always been higher than in most other rich countries, mainly because of Japan’s efforts to preserve small, inefficient farms and part-time farmers, a vital source of votes and money for the LDP. Consequently, even in 2013, before the depreciation of the yen and the post-Covid bout of inflation, Japanese households had to devote 24% of their total consumer spending on food eaten at home or in restaurants. By contrast, it averaged just 19% in the 27 EU countries, 14% in Germany, and 12% in the US. Then came Abenomics and the deliberate effort to weaken the yen. A weak yen raises the yen price of imports, and the latter account for 60% of food consumption (as measured by calories). As a result, food prices have risen 25% over the last five years and food now takes up 28% of the household budget. To afford to eat, consumers have had to buy four percentage points less of everything else. That’s one reason real (price-adjusted) consumer spending today is lower than it was back in 2013.

Import-intensive food and energy account for 85% of the total price increase since 2020. By contrast, prices for the entire rest of the economy are up only 4% from 2020.

Unfortunately, wages are not rising as fast as prices. Sure, the much-ballyhooed shunto talks have produced an average 5% wage hike, but only for the 16% of the workforce in the unions. Raises for workers at small and medium-sized non-unionized companies are much less, not even the 3% nominal hike sought by the Bank of Japan (BOJ). As a result, real wages—i.e., wages adjusted for rising prices—have fallen each year for the past three and are still falling through May of this year.

Social Anxiety Over Cuts In Social Security

Social security benefits per senior have already been cut by 25% hit in constant 2015 yen, from ¥2.4 million per senior in 1995 to just ¥1.8 million in 2023. Moreover, due to a so-called “macroeconomic slide” introduced in 2004, benefits per recipient will be cut 1% a year in price-adjusted terms for the next couple of decades. On the one hand, social security benefits are indexed to consumer inflation. So, if prices rise 3%, so should the benefits. On the other hand, due to the ongoing drop in the ratio of workers to retirees, benefits will be cut. So, if prices rise 3%, benefits will rise only 2%. In 2014, social security benefits were sufficient to replace 63% of the average lifetime earnings of a beneficiary. The plan is to reduce this to 50% by around 2047.

After that, the 2004 law says it should not be reduced below 50%. But what happens if tax and premium revenues are not sufficient to maintain even 50%? Will further cuts be made? Anxiety about this, as well as health insurance, exerted a big impact on voting behavior, as I’ll now discuss.

Anxious Aged Show Less Support for Consumption Tax Cut

At least one of the primary reasons the CDP underperformed was a significant generation gap in attitudes toward using a temporary cut in the consumption tax to mitigate the pain caused by high prices. None of the parties proposing such a cut offered a way to finance it. The LDP tried to exploit this lapse, with Prime Minister Shigeru Ishiba saying: “If we were to implement such a policy, how would we secure funding for social welfare programs,” like old age pensions and healthcare payments. Aged voters were far more anxious about this than younger voters, and both the LDP and CDP are very dependent on these older voters.

The older the age group, the more likely they are to support the LDP, Komeito, the CDP, or the Communists. The CDP’s support among voters under age 50 was dwarfed by support for the DPP and Sanseito. Now, consider a Nikkei-TV Tokyo poll which shows support for the consumption tax cut by party. Notice how the question is couched: “Maintain the consumption tax rate to finance social welfare or cut rates even by issuing deficit-covering bonds.” There was no option of cutting consumption tax rates by finding an alternative source of revenue, such as a rollback of corporate tax cuts. Had there been a third option, the answers might have been different. In any case, many voters may have inferred that cutting the tax endangered financial support for social welfare; this purported dilemma made older voters anxious.

Aside from the far left, the Communists and Reiwa, the older the voting base of the party, the less likely were its supporters to approve a tax cut that they were told could endanger the social welfare benefits they were already getting or would soon get. Only a small fraction of CDP voters supported a cut in the consumption tax; a significant majority said to keep current rates and did not support their party’s call for even a one-year elimination of the tax on food. By contrast, the majority of DPP and Sanseito supporters, who are younger, did support a tax cut. (The DPP proposes halving the tax on all items until real wages rise steadily; the Sanseito proposes eventually eliminating the tax and replacing it with more deficit-covering bonds.)

Poor handling of the tax issue is not the sole reason for the CDP’s underperformance, but I believe it was a major factor. It remains unclear whether the LDP's loss will result in any cut in the tax.