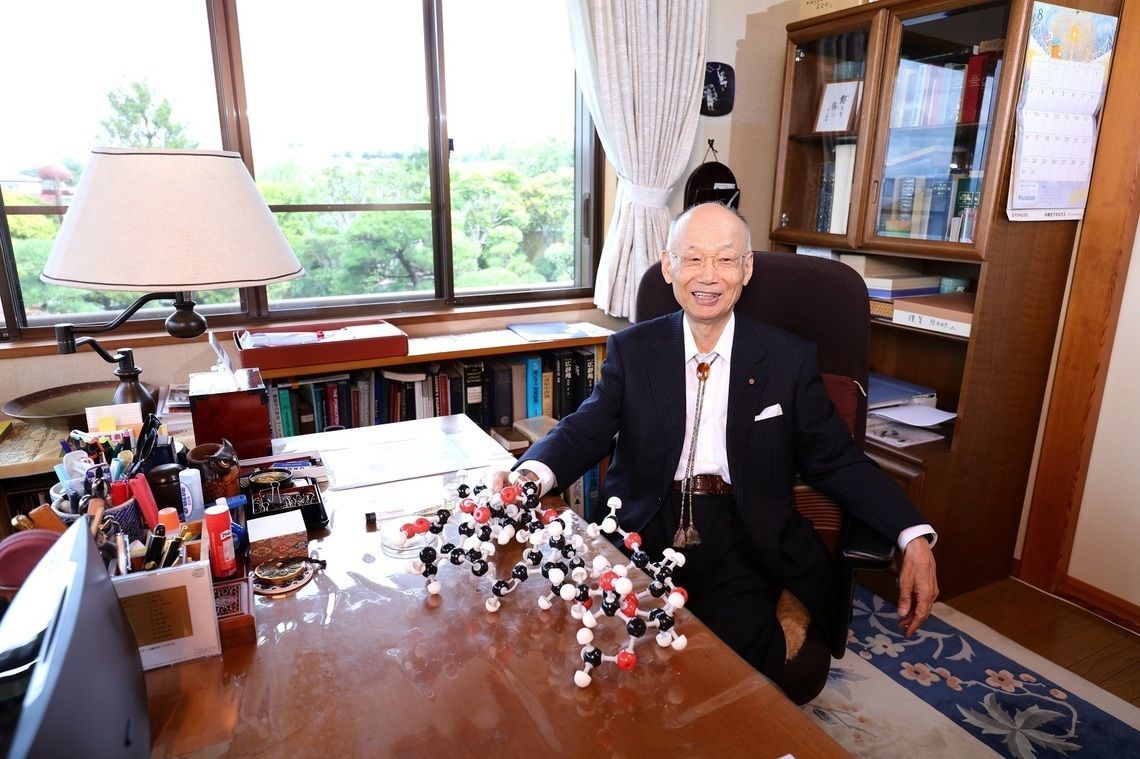

On October 5, Karolinska Institutet in Sweden announced that it was awarding the 2015 Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine to three people, one of whom is 80-year-old Satoshi Omura, distinguished emeritus professor at Kitasato Institute.

Omura, who is renowned in the world of chemistry, had been a Nobel Prize candidate before, but other scholars were more deserving for the prize.

Omura received the prestigious award for his discovery and development of ivermectin, a wonder drug used for treating river blindness (onchocerciasis), which is prevalent in tropical regions such as Africa. New chemicals were produced from microorganisms found in a golf course in Shizuoka Prefecture, in collaboration with Merck, a global pharmaceutical company. The company has developed antibiotics that get rid of a huge number of animal parasites.

Onchocerciasis is carried by blackflies with worm larvae, which infects the host with heartworms and can cause blindness in humans. However, since all it takes is a small dose of ivermectin to treat heartworm infection, the World Health Organization (WHO) has received an offer from Merck to administer the drug to 300 million people every year for free. The WHO expects the disease to be eradicated by 2020.

One thing that sets Omura apart from many Japanese Nobel Prize winners in previous years is that his background is far from that of the so-called intellectual elite.

He didn’t have any interest in studying at the university as he had to take over the care of his family’s farmhouse in Yamanashi, and he was dedicated to sports in his junior high school and high school years. He was so good in cross-country skiing in high school that he participated in a national athletic meet. After advancing to the nearby University of Yamanashi, he was able to study abroad in his mid-30s.

When Omura was hired by the Kitasato Institute, his position was “technical assistant.” Not only did he assist in experiments and data collection, but as part of his job, he also had to erase the writings on the blackboard whenever a professor would come to class.

With his good track record in experiments and papers, however, in a few years he was promoted to assistant professor. Then in 1971, at 36 years old, he went to the United States to study at Wesleyan University under Professor Max Tishler. Omura was introduced to Merck by Professor Tishler, who was a laboratory director at the company, and this led to the development of ivermectin.

Hot spring facilities in his hometown

Another side of Omura that makes him a unique individual is that he is an art lover and collector. He built an art museum in Nirasaki, Yamanashi Prefecture, his hometown, and donated his entire artwork collection to the City of Nirasaki. He is also the owner of a hot spring facility located next to the art museum. He built the facility with the aim of attracting tourists.

Omura explained, “Hot springs are always being dug around here. Tourists and people from other regions will come if there is a hot spring.” It is really interesting that he came up with such an idea 10 years before he achieved success and gained recognition as a researcher.

In August, when a reporter asked him about the hot spring, Omura touted the appeal of the hot spring: “The funds are revolving because there is a certain volume of visitors. They can watch Yatsugatake and Kayagatake from an open-air bath with the water flowing.

More than anything, the quality of the hot water is great.” During fall, the autumn leaves on the Koshu road create an amazing sight. It would be fun to visit the land that Dr. Omura has developed and set up a hot spring and art museum in.

The four faces

At a party held this July in honor of Omura for receiving the Canada Gairdner Global Health Award, an official at the Kitasato Institute introduced the four “faces” of Omura, according to Rensei Baba, Omura’s biographer and a former editorial writer at the Yomiuri Shimbun.

The first face was that of a researcher. He transformed from night high school teacher in Tokyo to researcher, who discovered a number of antibiotics and worked at the forefront of the eradication of severe tropical diseases. His has returned about 25 billion yen of patent royalties, led by international industry-university cooperation, to study sites, a record that will not be broken in Japan anytime soon.

The second face was that of a corporate manager. He rebuilt the Kitasato Institute, which was in a financial gridlock and built a new hospital. His financial knowledge accumulated through self-study drew out a clever management sense that even professionals in the field acknowledged.

The third face was that of a leader of various circles. He was also known as a collector of paintings with a deep knowledge of art. Also, after being asked, he served as president of the Joshibi University of Art and Design for 14 years. He was very enthusiastic about the scientific enlightenment of the people in his hometown.

The fourth face was that of a human resource developer. Thirty-one of Omura’s students became professors, and over 120 of them received a university degree. He gives a fair chance to everyone and does not fail to support them as long as he sees that they are motivated.

Baba commented on Omura’s background: “[He] signed contracts with foreign companies in the 1970s when cooperation with industry in Japan was still rare, and he had a remarkable track record that saved a lot of people from illness. This led him to winning the Nobel Prize. Omura is in an amazing place where he is at the top of the class, not only as a researcher, but also as a corporate manager and educator.”