In the post-apocalyptic horror film, A Quiet Place, survivors try to escape from blind alien invaders with an acute sense of hearing by being completely quiet. Japan today, facing the return of Donald Trump to the White House, also hopes to avoid the monster’s attention.

“Being off the radar is the best strategy for us,” says Tokyo University scholar Sahashi Ryo, a prominent expert on international politics in East Asia.

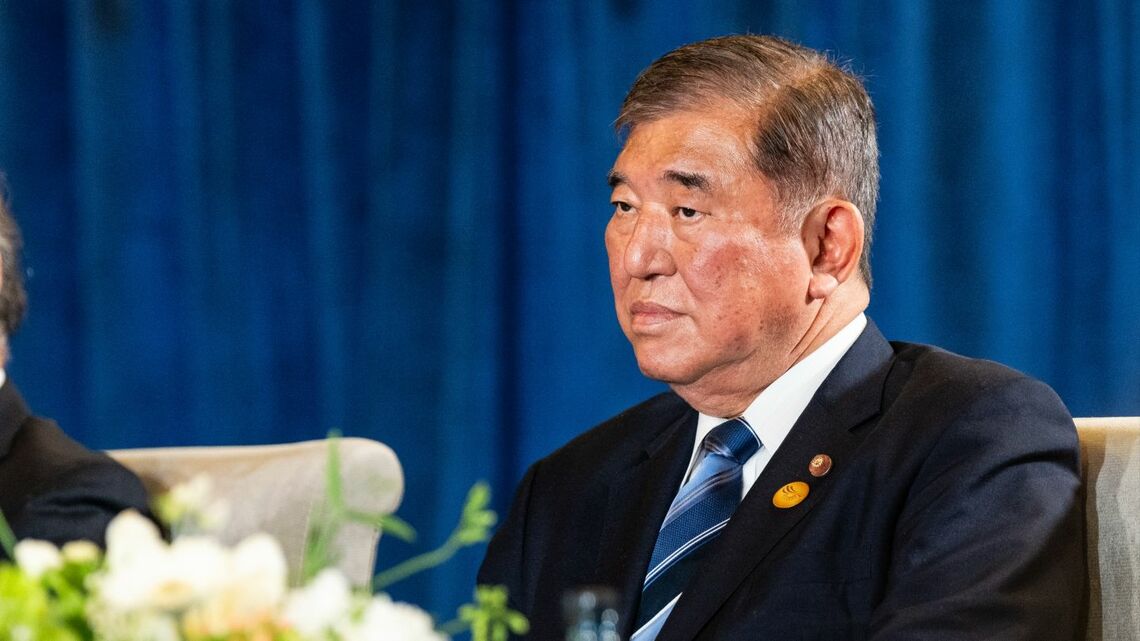

A former senior American official with long experience in Japan suggested to close friends that Prime Minister Ishiba Shigeru follow that approach, even advising him not to rush to visit Washington. But the Prime Minister has decided instead to walk onto the path of danger, meeting Trump at the White House on February 7th.

Ishiba does not want to join the growing list of American allies who have made it on to Trump’s target list – headed by Canada and Mexico, but including Panama, Denmark, and indeed the entire European Union.

The latest back and forth on the tariffs imposed on Canada and Mexico – with China perhaps to follow – seems to reinforce the belief that Trump would simply use tariffs as a bargaining chip. But in his own repeated remarks, it is clear that Trump sees these tariff measures as a means to not only provide revenue but also to restructure the world economy and force production back to the U.S.

Whatever Trump’s intention, Ishiba comes bearing the usual basket of presents, designed to calm the beast and stay off his wildly swinging radar path.

It is a well-crafted package of offerings – increased purchases of U.S. shale oil and natural gas, more purchases of American defense equipment as part of its defense buildup plan, while pointing to the record of Japanese investment in creating manufacturing jobs in the U.S. He is likely to avoid the touchy subject of the decision to block Nippon Steel’s purchase of U.S. Steel.

Ishiba has signaled that he does not anticipate smooth sailing in Washington. Responding to reporters on how he would deal with demands for even more defense spending, Ishiba said it was possible that 2 percent of GDP may not be enough, but “that is for Japan to decide, not the U.S.”

In a short speech to a global dialogue last week, organized by the Foreign Ministry thinktank Japan Institute for International Affairs, Ishiba pledged to strengthen the U.S. Japan alliance. But he quickly added that he planned to “engage in candid discussion” in Washington, diplomatic code words for a less than warm gathering.

Ishiba knows he cannot reproduce the close relationship that former Prime Minister Abe Shinzo had with Trump. The American leader refers to Abe constantly when Japan comes up, but he will quickly find the new Japanese leader is not a mere extension of Abe.

“Ishiba’s style goes counter to that of Abe – he is not a flatterer,” says Richard Dyck, Tokyo-based director of Japan Industrial Partners who has been part of a study group attended regularly by Ishiba.

The tariff wars have already come

Asked to describe the greatest impact of a Trump presidency on Japan, a former senior Japanese foreign ministry official who was deeply engaged in negotiations with the first Trump administration replied with just one word: “Tariffs.”

Japan, so far, has not been on Trump’s tariff list – next in line is the European Union and the tariffs on Mexico and Canada are only paused for a month. The 10 percent tariff imposed on China may also lead to some kind of negotiation. But if those pauses prove to be temporary, Japan will be a defacto victim as well of the widening economic war that Trump has unleashed.

The cross-border tariffs would effectively dismantle the U.S.-Mexico-Canada trade pact that was negotiated during Trump’s first term. In that framework, Japanese firms have set up hundreds of factories in both Mexico and Canada to create an integrated North American supply chain. Some 1,300 Japanese companies operate in Mexico alone.

The auto industry would be the first to feel the impact of these tariffs, not only Japanese firms but also U.S. and Korean firms, all of which operate plants in both Canada and Mexico, not only to assemble vehicles for export to the U.S. market but also the vital car parts that go to plants inside the U.S. Nissan alone exported 326,000 vehicles to the U.S. from Mexico.

The tariffs against China, on top of tariffs already imposed, will also impact Japanese firms that use China as a manufacturing base for exports. A growing trade war with China would of course have broader consequences for Chinese growth and hit Japanese firms that produce for the Chinese market.

The confrontation with China

In some circles in Tokyo, echoed by American policy makers, there is a hope that Japan’s role as an anchor in an anti-China confrontation will ensure that it remains off the Trump list of bad actors.

Traditional conservatives who have a hawkish view of China hold some key positions in the Trump administration, such as Secretary of State Marco Rubio and National Security Advisor Michael Waltz.

In that framework of confrontation, the U.S. may look to strengthen security ties with Japan and other partners in the region, predicts Randall Schriver, a former defense official in the first Trump administration, speaking to the JIIA gathering last week.

Others are concerned that Trump may opt instead for some ‘grand bargain’ with Chinese leader Xi Jinping, a new version of a “G2” with China that effectively excludes Japan. But most experts dismiss that worry.

“The danger of that is pretty low,” says Stanford China scholar Thomas Finger, a former senior intelligence official. If Trump wants to go to China to see Xi, “they will be delighted to have him there.

Trump will go because it will be a great personal triumph.” But the key issues on the table are difficult economic ones – technology competition and market access. The tech billionaires want access to China that is not easy for the Chinese to give, the China scholar tells Toyo Keizai Online.

“Even if Trump and Xi meet, it is not the start of G2,” agrees Tokyo University expert Sahashi. “Military-strategic competition will continue.”

Ishiba’s own China Card

Prime Minister Ishiba is already headed in a very different direction – a concerted effort to improve relations with China, and with the rest of Asia, particularly South Korea and key countries in Southeast Asia, to lessen the harsh impact of the return of Trump and the drift into global economic warfare.

Ishiba’s view of defense policy is focused less on the needs of the alliance with the U.S. than on the importance of strengthening Japan’s ability to defend itself. His advocacy of an Asian NATO has been widely misunderstood as a further subordination to American strategic goals. Rather, as Foreign Minister Iwaya Takeshi explained in the recent issue of Bungei Shunju, the aim is to create a “multi-layered security system for Asia.”

In unscripted remarks to the Global Dialogue, Ishiba spoke passionately about how Japan needed to mark the 80th anniversary of the end of World War Two by engaging in a serious examination of the decision to go to war and its defeat. “It is time for us to revisit and review the war experience,” he said. He called for Japan to understand “how to position itself in the world to create a world with more peace.’

There is a comparable interest in China, observes Stanford scholar Fingar, the former Deputy Director of National Intelligence. China has been reaching out particularly to Japan, to Europe and to others, seeking to repair the damage done by its alliance with Russia and Vladimir Putin.

“The Chinese smile diplomacy is partly due to fear of being isolated,” Fingar told Toyo Keizai. “They have buyers’ remorse because of lining up with Moscow,” with growing criticism within China that it has not been a good deal. But China is also motivated by its own interests.

“The Chinese want to bolster relations because it is useful for a domestic audience. Japan is in that category – if you can divide it from the Americans, it can fuel doubts about the reliability of the Americans. But the big motivation is China’s economy. They don’t need to have friendly relations with Japan for strategic reasons, but they need Japan to continue to play in the Chinese economy.”

The next months will be a test of how far China is ready to go to really improve ties with Japan. “We need some commitment from their side,” says Sahashi, including clear steps to shelve economic coercion, protect Japanese citizens and investors, and ease their military pressure on the Senkaku islands and the East China Sea.

The summit in Washington this week, and the trade war that has been launched, will likely encourage both Tokyo and Beijing to go down this road. But in order not to openly challenge the monster, it will be done quietly.