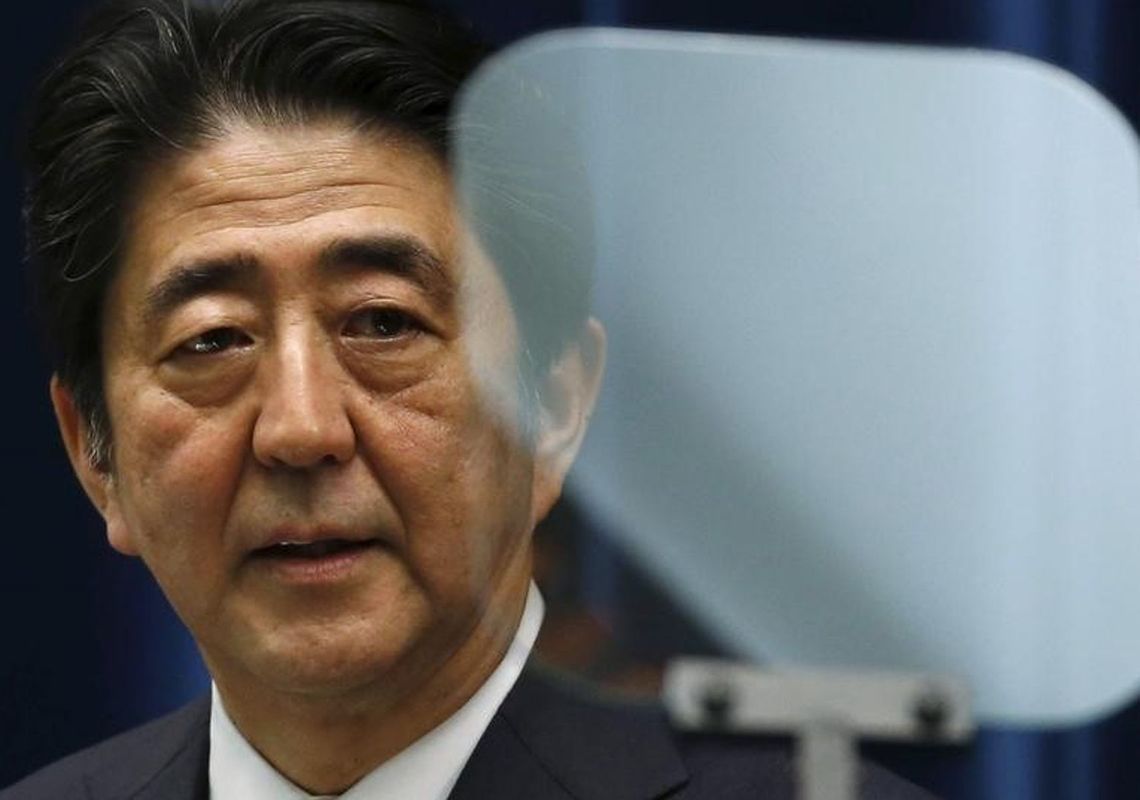

Professor Chris Hughes is Head of the Department of Politics and International Studies at the University of Warwick, in the United Kingdom. He is also an associate in research at Harvard's Reischauer Institute of Japanese Studies. He recently published a monograph entitled Japan’s Foreign and Security Policy Under the ‘Abe Doctrine’: New Dynamism or New Dead End? We talked to professor Hughes about Japan’s new security legislation passed by the Lower House, and where Japan goes from here.

The new security legislation has passed the Lower House, but generated a great deal of controversy, and now moves to the Upper House. Are you surprised by the backlash against the new legislation?

I was not especially surprised at the backlash, given that the LDP and New Komeito submitted to the Diet such a wide range of complex legislation that it was bound to raise suspicions among the opposition parties and the general public. The proposed legislation is so intricate that it seems even some LDP members did not understand it.

That all said, I’ve been most surprised by the quite limited extent of the backlash. The proposed legislation, in my view, is pretty radical in the way it opens up the possibility, longer term, for many scenarios for collective self-defense.

But the LDP-New Komeito coalition has gotten away with it quite lightly. The opposition has been reasonably determined, and caused a few wobbles for the coalition. But if it could not coalesce to make a reasonable case of countering the government on security issues, it would be truly hopeless rather than just hopeless. And in the end, it did not hurt the LDP that much. The LDP-New Komeito position has remained pretty solid, and that was enough for them to have the confidence to push it through the Lower House.

The LDP and New Komeito probably have been taken aback somewhat by the public disquiet. But that did not stop them from ramming the legislation through in any case. And I suspect they think support may recover somewhat after September, once the legislation is finally passed in the Upper House. The public still supports the LDP well above any other party.

Washington's special treatment of Abe

What accounts for the red carpet treatment he received in Washington? It was only last year that Washington was quite upset with Abe because of his visit to Yasukuni Shrine.

The U.S. rebuked Abe for the Yasukuni visit. Abe managed to do some repair work during Obama’s visit to Tokyo in April 2014. He has kept quiet on history issues, keeping it off the bilateral agenda. The U.S. needs Japan for its strategic rebalance toward Asia. There remain misgivings in Washington about Abe’s belief in historical revisionism, but he is the best option the U.S. has right now.

Much of the motivation for the summit was concern about the rise of China. The strategic imperative is there for the U.S. and Japan to get even closer, to deal with that. When you put all of these factors together, it becomes clearer why the U.S. decided to put its misgivings about Abe to the side for now.

You argue that the foreign and security policies pursued by Abe represent a “radical” shift that one day might even be called the “Abe Doctrine.” What would constitute an “Abe Doctrine”?

When we use the term “doctrine,” we are using a reasonably broad-brush term. For example, there has long been talk of a “Yoshida Doctrine,” after former Prime Minister Shigeru Yoshida. But when you look at the content, it evolved over time.

The three components of the Yoshida Doctrine were: 1) low military posture; 2) a security treaty, and later alliance, with the U.S., with the caveat that Japan would heavily hedge so as to extricate itself when possible from commitments to the U.S., while focusing on economic revival and growth; 3) a gentle, quiet reintegration of Japan into the East Asia region, including engagement with China.

With some variations, these have been the principles of Japan’s foreign policyーthe Yoshida Doctrineーfor most of the postwar period.

The Abe Doctrine is a radical departure from that 3-part stance. Much of what Abe is promoting has been in the LDP manifesto for years, and many LDP leaders have had this intent. Abe comes from the Kishi faction of the LDP, which has captured control of the party. It is very revisionist and radical in nature.

Nobusuke Kishi (former Prime Minister and grandfather of Abe) regularly talked about restoring Japan to great power status, including a leadership role in Asia, and warrior status in the Cold War against communism. That ideological bent is part of the Abe Doctrine, and gives it energy and dynamism.

On the military side, Abe is clearly pushing hard to make Japan a more capable military power, crossing a watershed to allow Japan to use military power for national security interests. That is quite radical.

A key element of the Abe Doctrine is the notion of breaking free from the postwar regime, both domestically and internationally, which Abe believes is rooted in Japan’s defeat in World War II. In his view, the Yoshida doctrine is a regime of defeat. Until the postwar regime is cast off, Japan cannot be an autonomous great power. Until then, Japan cannot take its rightful place alongside the U.S. and other developed countries.

Abe won't apologize to China or Korea

Is the notion of Japan as an autonomous great power just a dream? What would that look like?

I think it is just a dream, or mirage. Japan is never going to be an autonomous great power, in part because it will never be able to defend itself, by itself, unless it acquires nuclear weapons, which is unlikely and is laden with risk. It would be counterproductive. And Japan’s national capabilities are shrinking, relative to China. In reality, it is fairly unlikely that Japan will emerge into an autonomous great power.

How do you assess US-Japan relations?

The alliance is proceeding fairly well. But there are a lot of problems lurking in the background that are going to slow down progress if they are not sufficiently addressed. Japan-China relations are a little bit better, a little more stable. Both sides have stepped back from the worst risks over the disputed territory. But there remains a stalemate in that dispute.

The United States has tied itself to a Japanese leader and regime in Japan that is always going to be problematic with respect to history, and with respect to what really are contending values. If Abe’s foreign policy were generating good results consistent with US interests, the problems Abe causes could perhaps be managed. But the results of Abe’s foreign policy are not great.

The August 15 statement planned by Abe concerning the 70th anniversary of the end of WWII seems likely to be the next watershed. What do you expect?

I expect it will be a missed opportunity. I don’t think Abe will challenge the Murayama or Kono statements, but he will do his best to marginalize them. He simply won’t talk about them. He will not apologize to China or Korea. He’ll try to keep the focus on the future, and talk about all of the great things Japan has done in the postwar period.

Abe will not feel obliged to seize the opportunity to try and ease some of the suspicions his government has generated in China and Korea. And in the wake of his visit to Washington, he thinks he will get away with this approach. He probably will get away with it.

No one will be helped by this; certainly not the U.S., which has tied itself to Abe. In turn, Abe generates suspicions within China and Korea, which puts the U.S. in an awkward position.