In Tokyo’s corridors of power, Prime Minister Fumio Kishida is increasingly being referred to as Kento-san (from the verb kento suru, i.e., “to consider”). He considers doing this or that, but somehow rarely gets around to doing it. Nowhere is this truer than in the case of “new capitalism.”

After months of deliberation, the government came up with only “weak tea” on both of its planks: 1) boosting consumer purchasing power by correcting Japan’s maldistribution of income between companies and people; and 2) jumpstarting productivity growth by reviving Japan’s high-growth-era record of creating a host of new, entrepreneurial companies.

Insiders say that Kishida and his team are sincere regarding these goals. However, when Kishida meets with resistance on any issue, he usually backs down.

Let’s look at redistribution in this column and examine entrepreneurship in the next.

Corporate Taxes

For more than two decades, the Japanese government has played a big part in Japan’s skewed income distribution, largely by lowering taxes on corporations from a top rate of 52% in 1994 to 30.6% at present. while raising them on people via the consumption tax. That’s one of the main reasons consumer demand, hence GDP growth, is so anemic.

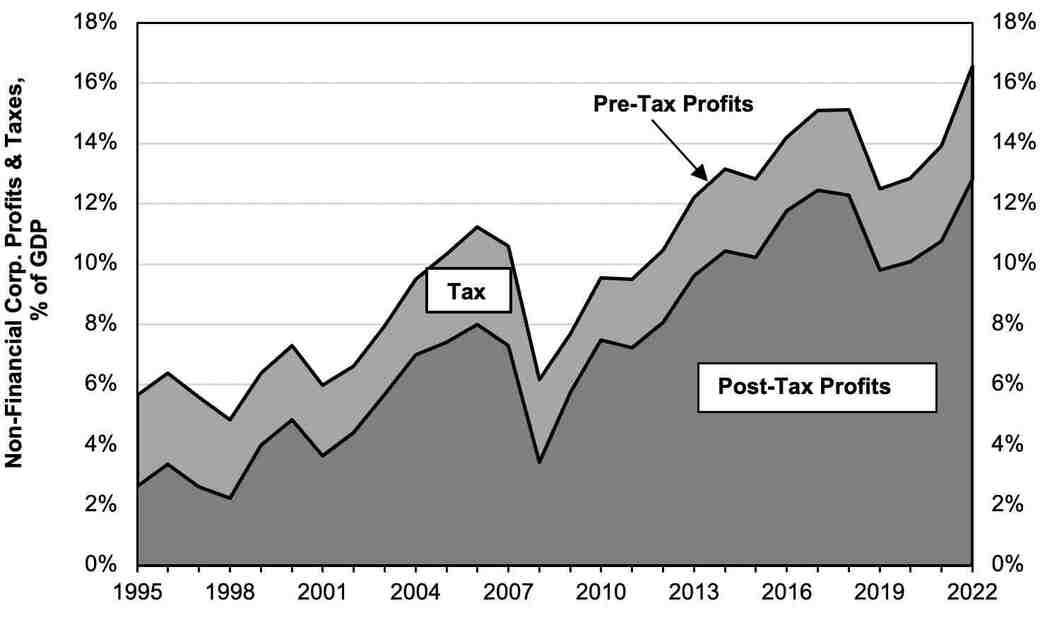

Let’s look at the data. From 1995 to 2022, pre-tax profits of nonfinancial corporations soared from 6% of GDP to almost 17%. That was due to the combination of wage austerity and cuts in interest rates.

However, tax payments on that income rose just a smidgeon, from 3% of GDP in 1995 to an estimated 3.8% of GDP in 2022. Consequently, post-tax profits exploded from 2.2% of GDP to nearly 14%. In short, while pre-tax profits tripled relative to GDP, post-tax profits rose almost sixfold (see chart below).

The government and the Keidanren business federation claimed that the tax cuts would boost both investment and wages. Neither promise came true. In fact, companies are raking in so much cash that lies fallow in paper investments (zaitech) that income taxes could double and corporations would still have more than enough money to raise both wages and investment.

In effect, companies are taking more money out of the real economy than they plow back in, and that forces the government to maintain chronic deficit spending to avoid recession.

Rolling back some of the past corporate tax cuts would be one of the easiest ways to fulfill the “New Capitalism” agenda. Back in May, an anonymous member of the Liberal Democratic Party (LDP) Tax Commission told Jiji Press, “While we won’t be able to drastically raise [the corporate tax], we need to implement a structural transformation that suits the current situation of Japan.”

The opportunity to begin this process came with Kishida’s decision to double defense spending to 2% of GDP over the coming five years. Funding the entire expansion via corporate taxes would amount to a hike of about ¥4 trillion ($30 billion), compared to the ¥17 trillion companies paid in 2021.

The powerful head of the LDP Tax Commission, Yoichi Miyazawa, a cousin of Kishida’s, wanted cuts in other spending to fund the defense hike. However, if such cuts were not enough, he told Reuters in October, he’d consider raising taxes on affluent individuals as well as corporations.”

The forces of resistance within the Liberal Democratic Party (LDP) and the Ministries, quickly came to the defense of the corporations. A senior official at METI told me in November that blocking any hike in corporate taxes was the Ministry’s highest priority. Since the purpose of my interview was to talk about METI’s efforts to promote startups, that was telling.

In the end, the government simply postponed any final decision, thereby falling back on higher budget deficits. First, it proposed that only a tiny ¥700 billion ($5.4 billion) out of the needed ¥4 trillion would be covered by hikes in corporate taxes. The rest would be covered by spending cuts and a shift in tax revenue that had been scheduled to deal with rebuilding from the Fukushima disaster.

However, the LDP Tax Commission said a final decision would wait until next December and would be implemented sometime between 2024 and 2027. When a leader of the Shinzo Abe faction said Kishida had not asked the voters for a mandate to raise taxes, in 2022 on hiking taxes, Kishida said that he did not expect any decision on a tax hike until after a Lower House election, which is not required until 2025. His aides tried to “walk back” his comments, but the upshot is that no one really knows what will eventually be done.

Wages

Wage suppression—and hence weak consumer purchasing power—is at the heart of Japan’s inability to grow (https://toyokeizai.net/articles/-/476082 in English. Once again, Kishida has said the right things but offered little action to remedy the problem.

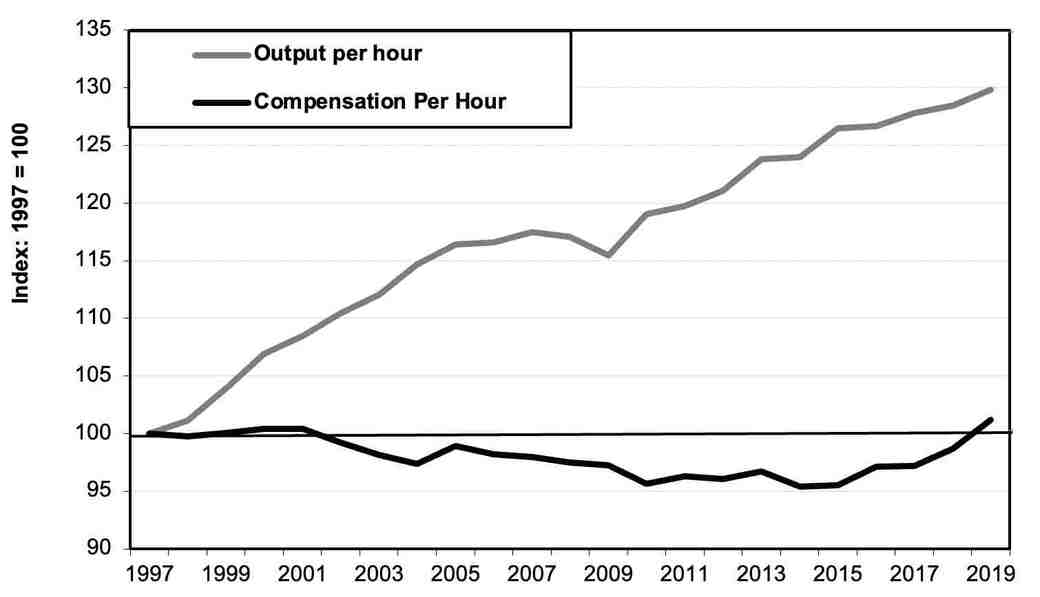

In a healthy market economy, real wages per hour should grow in tandem with the growth in output per hour. While this linkage has broken down in most rich countries, the worst gap is in Japan.

In the two decades from 1997 through 2017, the average worker produced 28% more GDP each hour, but real compensation per hour (wages plus benefits) fell by 3%. Only in the last few years has the labor shortage begun to yield some recovery in wages, according to the OECD (see chart below).

However, figures from the Ministry of Health, Labor, and Welfare (MHLW) show a continued decline in real wages per month because an economic slowdown reduced overtime pay and the hours of part-timers. The government is hoping that this year’s labor negotiations (shunto) will yield a substantial hike in wages, but a slowdown in the US and Europe will likely make Japanese companies cautious.

So far, the most substantial move by Kishida has been to continue Tokyo’s policy since 2010 of raising the minimum wage by 2-3% a year in order to reach a national average of ¥1,000 ($7.57) per hour. In August 2022, the government raised the minimum wage by 3.3% to ¥961. This is the biggest hike since comparable records began in 2022.

This has a big impact because raising the minimum wage helps not only the with wages below the minimum but those 10-15% above it. A 2014 IMF study calculated that about 16 million regular and non-regular workers—30% of all non-managerial employees—earn less than ¥1,068 per hour.

They would benefit greatly if Japan reached the ¥1,000 goal and then moved above it. Kishida has so far said nothing about what he will do once the ¥1,000 goal is reached in the next year or two.

Back in December 2021, the Kishida administration raised the level of the temporary tax breaks granted to companies that raise wages by at least 3-4%, but just for two years. However, the history of these tax incentives show that companies do not grant permanent wage hikes in return for temporary tax benefits.

Beyond that, Kishida, like his predecessors, has done nothing more than to ask companies to raise wages. Companies, however, do not raise wages in response to a request from the Prime Minister. They do so only when labor’s bargaining power, or labor market supply/demand conditions, or regulations pressure them to so.

While Kishida has taken action where he has no power, he has not taken action where he does have the power. Japanese law already mandates equal pay for equal work between both men and women and between regular and non-regular workers. However, no agency of government is mandated to investigate violations of the law and to prosecute offenders.

The labor inspectors of the MHLW do not do so because they consider it a contract issue. A source in the Kantei (Prime Minister’s Office) said that Kishida had issued some sort of directive on this, but provided no details. The MHLW has so far not responded to email requests for details, and there is no evidence of any action on this front.

Besides, a series of court decisions allow firms to practice “reasonable discrimination.” As a result, firms can get away with systematically paying unequal wages just by tweaking a tiny bit of the job. Real enforcement requires the government to create better standards on “equal work” to overcome the pro-employer bias of the courts.

Kishida said in December that he wants to launch a discussion with experts this month on how to achieve a virtuous cycle of growth and distribution. But it’s already been 15 months since October 2021 when, in advance of a Lower House election, he set up a so-called “flagship panel” on this topic, consisting of Cabinet Ministers and 15 private-sector members including academics and representatives from business lobbies and unions.

The problem in Japan is not a lack of ideas for Kishida to “consider.” It’s lack of the political will to do anything that steps on the toes of vested interests.