The most basic task of a political leader is to leave his country better off than he found it—or at least no worse. By this minimal goal, former Prime Minister Abe Shinzo failed miserably.

For years, voters bought his electoral tactic of announcing one lofty economic goal after another without offering the measures needed to achieve them. Today, however, Abe’s failure is so widely recognized that Prime Minister Fumio Kishida poses his “new capitalism” agenda as a thinly veiled corrective to Abenomics.

Like so many of his predecessors, Abe promised to restore Japan’s real (price-adjusted) gross domestic product (GDP) growth to 2% per year. He did not even come close. Initially, it looked like Abenomics was working, with GDP rising at a 3.2% annual pace from the fourth quarter of 2012 to the first quarter of 2014. This gave Abenomics unwarranted credibility.

In reality, GDP enjoyed that temporary spurt mainly because that is what economies do after a long slump. When Abe returned to power, GDP was no higher than it had been seven years earlier and so it enjoyed a cyclical uptick. This cycle has happened several times during the three lost decades, even though annual GDP growth has averaged less than 0.7% since 1991.

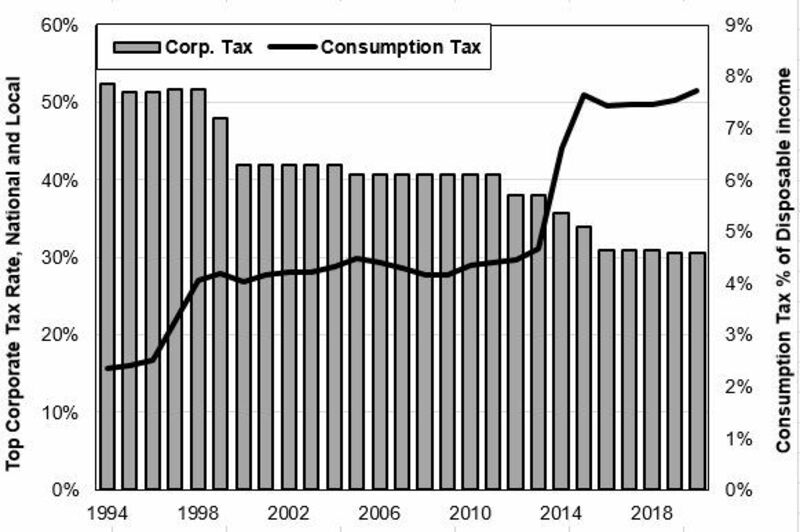

Then, in April 2014, Abe put a damper on growth by hiking the consumption tax from 5% to 8%. In a healthy economy, this would have caused nothing more than a brief sag in growth.

In Japan, by contrast, the hike suppressed growth for years, especially because it was followed by a second increase in 2019. As a result, from early 2014 to the end of 2019, i.e., before Covid-19 struck the economy, GDP grew at a barely visible annual 0.2% pace, just one-tenth of the pace Abe had promised.

GDP growth is, of course, just a means to an end: growth in living standards. Under Abe, the opposite happened. Living standards continued the decline that had begun in the mid-1990s; Abe inherited a bad situation and then made it worse.

For regular workers, real hourly wages fell almost 5% from 2012 to 2019. Moreover, during this period, 82% of the growth in jobs consisted of low-paid non-regular jobs. This further lowered wages because, as of 2020, while the average regular worker earned ¥2,500 per hour, temporaries got just ¥1,660, and part-timers a stingy ¥1,050. Abe’s response was to futilely ask companies to hike wages.

To get real results, he could have enforced Japanese laws that require equal pay for equal work between men and women as well as between regular and non-regular workers, by mandating the Labor Ministry to investigate and prosecute violations of the law. But he chose not to do so.

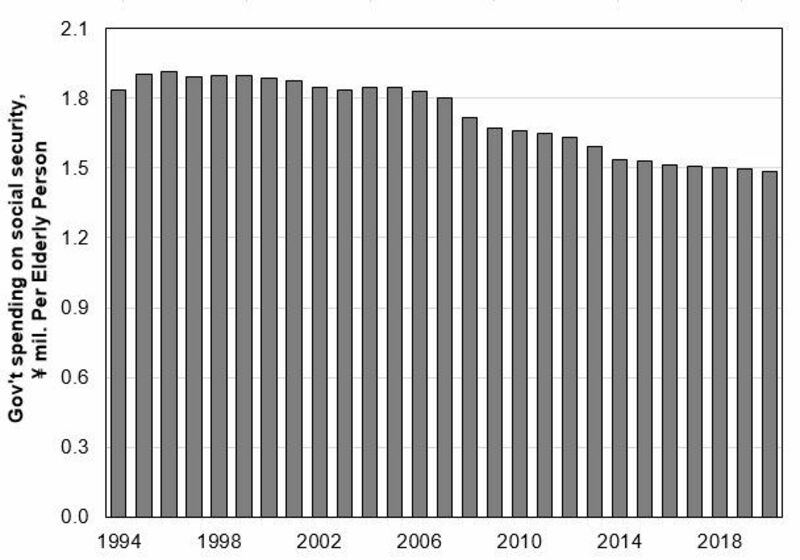

At the same time, Abe continued the post-2000 trend of cutting government spending on social security for the aged. During his tenure, old-age pensions per senior fell another 9%.

He also continued the policy of shifting the share of national income from people to corporations, by cutting the top income tax on companies from 38% to 30% while doubling the consumption tax to 10%.

Like his predecessors, Abe offered the “trickle down” theory that corporations would use the tax cut to invest more and raise wages. In fact, as shown by data presented to a meeting of Kishida’s Council on New Capitalism, between 2000 and 2020, the combined yearly profits of Japan’s few thousand largest corporations almost doubled, but their compensation to all workers combined fell 0.4% and their capital investment fell 5.3%.

When confronted by such facts, Abe’s supporters point to the growth of female employment as a major achievement of his “womenomics.” However, that is little different from the experience in most rich countries: when men suffer from wage austerity, more wives join the labor force to maintain family incomes.

Under Abe, 75% of the growth in female employment was in low-paying, dead-end non-regular jobs. Abe himself admitted that his 2013 promise to raise the female share of company managers to 30% in just seven years—a repeat of a goal Tokyo had set ten years earlier—was a flop. So, in 2015, he halved the goal to 15%, a target still far on the horizon.

Abe’s defenders also point to the end of deflation. However, Abe had always claimed that achieving 2% inflation—something the Bank of Japan governor claimed he could do in just two years—would restore growth and it has not done so. So, when Tokyo failed even to come close to the 2% inflation target, Abe’s supporters changed their mantra and now claim that just ending price declines is good enough.

In any case, the way that Abe overcame inflation was yet another blow to living standards. Healthy inflation is a result of robust domestic demand. By contrast, 93% of the price hikes during the Abe years stemmed from import-intensive products, like food, energy, apparel, and footwear.

That’s because Abe’s campaign to weaken the yen raised the price of imports. This kind of inflation simply shifts income from Japanese consumers to foreign producers, while raising profits at Japan’s big multinational companies.

Abenomics would have helped Japan if Abe had truly pursued his promise of structural economic reforms, i.e., the “third arrow” of the so-called three arrows of Abenomics. That, however, would have required stepping on powerful toes and, despite Abe’s unprecedented domination of the Diet, he chose not to spend his political capital in pursuit of reform.

Perhaps that is because he believed his own hype that conquering deflation would be a painless path to growth. To take just one example, consumers pay high food prices partly because the mammoth Japan Agriculture (JA) cooperative is immune from the Anti-Monopoly Law.

Abe claimed to have initiated a drastic reform of the JA, but, in reality, he ignored the advice of his own advisory council to break up the cooperative. Instead, he worked out a deal that the head of JA, Akira Banzai, more or less admitted would not result in any substantial change. Despite a few exceptions, hollow measures like this were the hallmark of Abe’s “third arrow” efforts.

There was one more thing Abe got wrong, but fortunately so in this case. Abe claimed that Abenomics was Japan’s “last chance” to revive. In reality, countries have lots of “last chances.” Japan’s continued corrosion under Abe does not mean that it cannot revive; it merely means that Abe blew his opportunity.

This article (without the charts) was included in a compendium of essays analyzing Abe’s legacy published by Japan Focus