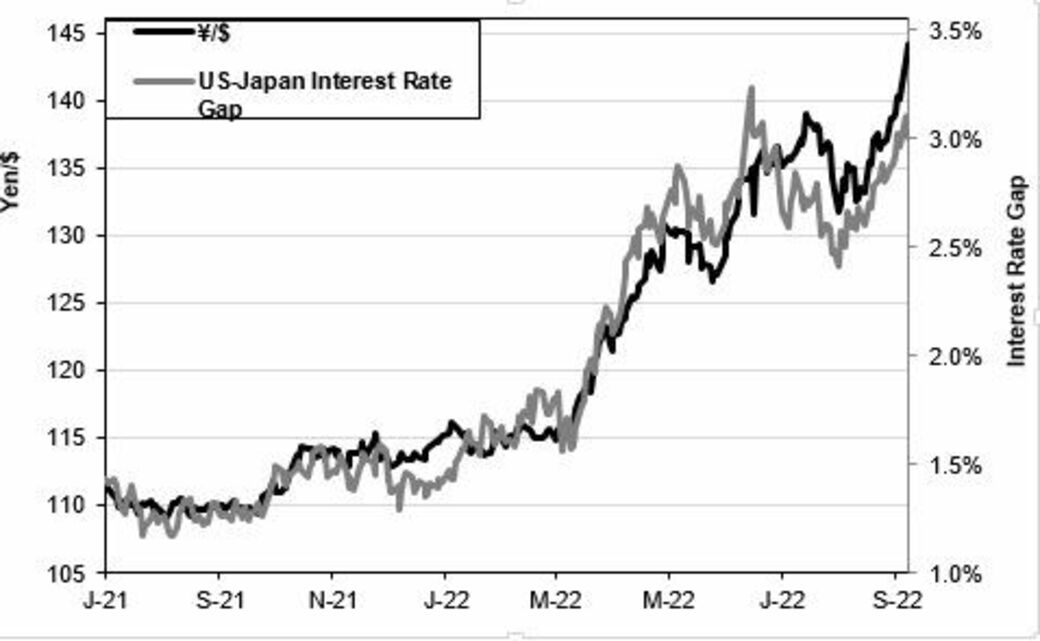

Global inflation, and the rising interest rates being used to counter it, are creating a big dilemma for the Bank of Japan (BOJ). If Japan’s domestic demand and inflation were the BOJ’s only considerations, keeping interest rates at near-zero levels would seem perfectly sensible. However, the side-effect is a steep plunge in the yen’s value, which weakens as the gap grows between interest rates in Japan and those in the US and Europe (see chart).

BOJ Governor Haruhiko Kuroda has repeatedly denied the dilemma, claiming that a weak yen is a “net benefit” because it boosts Japan’s exports. From time to time, Kuroda has complained about the yen moving too fast. But many economists and business leaders contend that the yen has become so weak that the costs are now greater than the benefits. It harms Japanese households by raising prices for food, energy, and other essentials.

In a June poll, nearly half of companies surveyed said the weak yen—then at ¥130/$—was hurting their business, while just 3% said it was helpful. The weak yen also forces the government to hike deficit spending to make up for weaker consumer purchasing power. Moreover, as the BOJ itself acknowledges, a weak yen does not boost exports as much as in the past.

Japan’s Inflation is Different From US, Europe

Just as cancer of the lung and the liver are different illnesses, so are the bouts of inflation hitting Japan, the US, and Europe. Different maladies require different remedies.

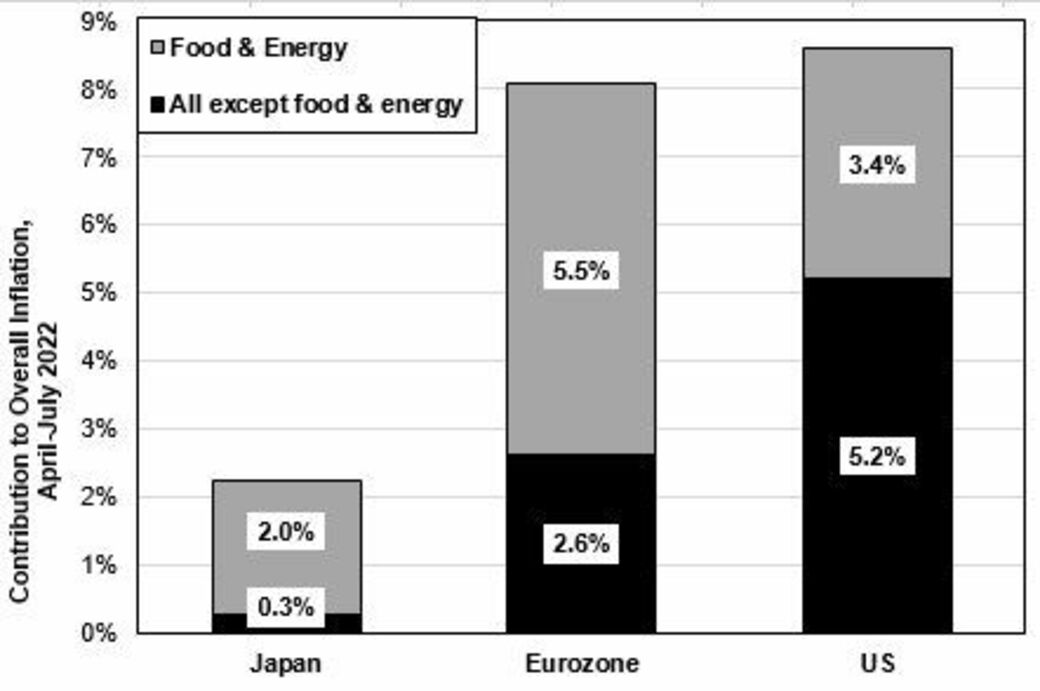

It’s not just that Japan’s headline inflation is far below that in the US and Europe—just 2.2% in Japan during April-July 2022 vs. 8.6% in the US and 8.1% in the 19 Eurozone countries. In addition, the source of inflation is different.

An overwhelming 88% of Japan’s inflation stems from the import-intensive food and energy categories, even though these items make up only 27% of consumer spending. All the remaining items—known as “core” inflation—account for a paltry 12% of Japan’s overall inflation, far below the 61% share in the US. The Eurozone stands in the middle at 32%.

Central bankers focus on core inflation because it is a better predictor of longer-term trends. By contrast, food and energy fluctuate a great deal in response to global events outside a nation’s control, from pandemics to war to the fluctuations in China’s growth. Their prices can drop even when core prices rise. That’s why inflation trends in the food and energy sectors are very similar in Japan, the US, and Europe.

Consequently, most of the disparity in headline inflation among Japan, the US, and the Eurozone stems from core inflation. Japan’s core inflation as of July was just 0.4%, far below the BOJ’s 2% goal. By contrast, core inflation has soared to 6% in the US and has reached 4% in the Eurozone.

This is a major reason why Kuroda sees Japan’s inflation as transitory and insists on continuing the BOJ’s near-zero interest rate policy. In its July Outlook report, the BOJ predicted that consumer prices (aside from fresh food) would fall back to 1.2-to-1.5% in fiscal 2023. In June, the OECD forecasted 1.4% core inflation for Japan in 2023, the lowest level in the OECD except for Switzerland. By contrast, central banks in the US and Europe fear that, unless they aggressively suppress inflation momentum now, it could become self-feeding and rise to even higher levels.

Demand-Pull Vs. Cost-Push

The other key distinction made by central bankers between “demand-pull” and “cost-push” sources of inflation. That’s because the two variants require different policy responses. The concentration of Japan’s inflation in food and energy suggests that global cost-push forces dominate Japan’s inflation. In the US, domestic demand-pull forces are stronger than cost-push, and in Europe, the two causes are more equally balanced.

Demand-pull means that aggregate demand is rising faster than the economy’s ability to meet that demand (i.e., aggregate supply). For a while, the economy will grow faster than is sustainable, i.e., “overheat.” Steady 2% core inflation is healthy; levels substantially higher reflect overheating.

In the US, the government handed out immense sums of cash to households out of fear that Covid-provoked mass layoffs could create a deep recession. However, much of that money was saved because people could not access all sorts of services. Now, that cash and pent-up desires are feeding excess demand.

The remedy is to slow demand by raising interest rates so that demand returns to balance with balance. Unfortunately, it’s hard to execute this slowdown without pushing the economy into recession. The higher and more protracted the inflation, the greater the difficulty of a soft landing. That’s why central banks like to hit the brakes sooner and harder.

By contrast, cost-push means that the prices of vital inputs have risen, sometimes because they are much harder to get, e.g., the semiconductor shortage that is hampering auto production or Russia’s cutoff of oil and gas to Europe. As a result, prices can climb even as GDP growth slows or even falls, a combination called “stagflation.”

In both Europe and the US, supply chain problems caused by Covid account for about a quarter of core inflation, according to the European Central Bank (ECB). Another quarter stems from people suddenly being able to buy services that they could not buy before.

Dealing with cost-push inflation is complicated. Suppose prices of vital inputs shoot up 10% in a one-shot event, but they do not keep rising year after year. Then, inflation will return to normal on its own. Initially, the US Federal Reserve and the ECB thought that was the current case and the BOJ believes that’s still the case in Japan.

If, however, cost-push pressures keep sending inflation rates upward rates over a prolonged period, people could change their behavior. Workers who expect inflation to last could demand higher wages. Companies could succeed in passing on higher costs to their customers. So far, there is little evidence of such a spiral. Wages are growing far more slowly than prices. Nor is there any surge in expected inflation over the coming five years by either consumers or financial markets in the US or Europe.

What is clear now is that supply chain shocks caused by Covid, the war in Ukraine, and, in Japan, the weakening yen, are causing a lasting episode of cost-push inflation. How prolonged remains to be seen. This is a tougher problem to address. How much does the ECB want to slow demand in an economy where GDP is expected to decline due to a shortage of energy?

Kuroda argues that Japan’s inflation is of the transitory cost-push variety. Hence, not only is there no need for Japan to raise interest rates, but doing so would undermine both GDP growth and the BOJ’s effort to attain healthy demand-led 2.0% inflation.

The conundrum is that Japan is not an island sheltered from outside financial storms. As other countries raise rates and Japan refuses, the result is a growing gap between interest rates in Japan and those elsewhere. So, investors shift money from Japan to the US and Europe, and the yen drops like a rock (see chart at outset).

The Cost Of A Yen That’s Too Weak

The dilemma arises because, contrary to Kuroda’s claim, a weak yen has big costs that now seem to outweigh its benefits in the view of a growing number of analysts. Most fundamentally, a weak yen raises prices for essential import-intensive consumer items, like food and energy, as well as assorted inputs needed by businesses. That leaves consumers and domestically-oriented businesses with less money to buy other items, especially those produced at home.

Paying more for imports transfers income from Japanese consumers and small and medium businesses to foreign producers. It also transfers income to domestic multinationals, who make more profits on their exports and foreign assets when the yen is weak.

The yen’s price-adjusted purchasing power for needed imports is the lowest it has been since 1971. It is one of the reasons—along with Covid, hikes in the consumption tax—that consumer spending has been stagnant for years and is now 4% lower than it was way back in 2013.

In addition, business investment is down 9% from its 2019 peak. Raising interest rates to bolster the yen would add to the headwinds hurting its recovery. Moreover, while the official unemployment rate in July was just 2.5%, an additional 3.7% of the labor force was listed as “employed person [but] not at work,” i.e., employees with no tasks who are kept on the payroll with the help of government subsidies.

It’s understandable why Kuroda opposes raising interest rates when private domestic demand is so weak and domestically-created inflation remains so low. However, the cost of this policy could be a continued nosedive of the yen.

Wither The Interest Rate Gap?

Currency traders keep going back and forth on the trajectory of the yen because their expectations of US inflation and interest rates also go back and forth. A minority of financial traders believe Kuroda will be forced to let 10-year bond rates rise above 0.25% and in June, they sold Japan Government Bonds (JGBs) en masse to force Kuroda’s hand.

The BOJ had to spend an unprecedented $80 billion in just one week to defeat them. No doubt, there will be further attempts. However, that makes the BOJ even more determined. If the markets breach the 0.25% line in the sand, where will it stop? For the past 25 years, those who’ve bet that the BOJ cannot prevent a hike in interest rates have repeatedly lost truckfuls of money. Those betting against the BOJ retort: past results are no guarantee of future outcomes.

The good news for Kuroda is that, even though the Fed is raising overnight rates, called Fed funds—its main policy instrument—such hikes do not move 10-year bond rates to the same degree. That’s because the hike in the Fed funds is only temporary.

In fact, when investors fear that tightening by the Fed will provoke a recession, the market typically goes into a so-called “inversion.” That’s a situation where the interest rate on 10-year bonds becomes lower than overnight rates.

In early September, the 10-year bond rate was lower than it was in June, even though the Fed funds rate had been hiked from 1.65% to 2.4%. So, it remains to be seen where the 10-year rate will go when the Fed raises overnight rates yet again at its September 20-21 meeting and if, as expected, continues to raise them at subsequent meetings.

Uncertainty is causing financial markets to go through big mood swings. Fasten your seat belts: the yen is going to have a bumpy ride.