Vladimir Putin’s war against Ukraine began, not in February of this year, but February eight years ago in 2014 when Putin seized Crimea and installed puppet governments in two eastern areas of Ukraine. He now demands that Ukraine recognize these as “independent republics.” Crimea, by the way, held 80% of Ukraine’s oil and gas deposits and had been a major source of the country’s export revenue.

What triggered Putin’s sudden aggression? The fact that, via the Euromaidan protests, the Ukrainian people dethroned his puppet in Kyiv, a man named Viktor Yanukovych. The uprising began when, on orders from the Kremlin, Yanukovych reneged on a pact with the European Union intended to lead to full membership. Instead, he wanted Ukraine to join Russia’s countergroup, the Eurasian Economic Union. In addition, Yanukovych had been tagged as the most corrupt ruler in the world. Putin’s seizure of Ukrainian territory began two days before Yanukovych fled to Russia.

Putin now says this year’s “special military operation” will not end until Ukraine meets his assorted demands. These range for acquiescing to Putin’s territorial conquests to adding a “neutralization” clause to the Constitution. The latter would prevent Ukraine from joining “any bloc,” not just NATO (which is not on the agenda anyway), but also the EU.

In the era of Brexit, it's stunning that desire to join the EU triggered ordinary Ukrainians to rise up against an autocrat ruled from Moscow. What drove these people to the streets? It was the linkage between joining the European community and making Ukraine an independent, liberal, and prosperous democracy.

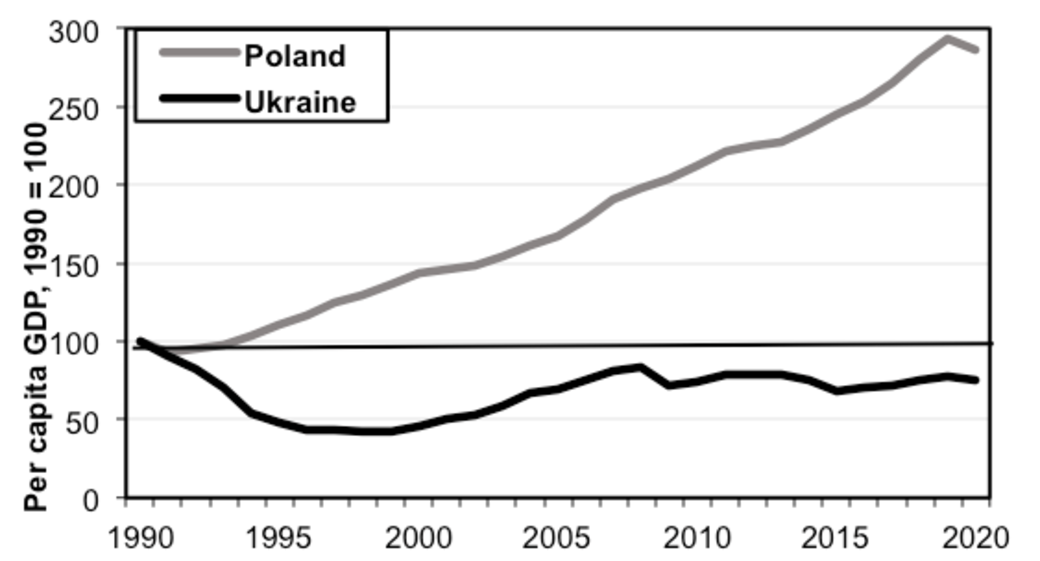

Part of this package is attaining European living standards, and this cannot be done without EU membership. Compare Poland, which hitched its star to Western Europe after the fall of the Berlin Wall in 1989, to Ukraine, which remained too tethered to Russia for too long. The Russian leverage has been so strong that, as late as 2002, someone in Moscow could shut down Ukraine’s electricity just by throwing a switch (thankfully, that’s no longer the case). Poland’s per capita GDP has tripled since 1990 while Ukraine’s per capita GDP halved in the 1990s and, as of 2020 was still 25% below its level three decades ago (see chart).

Compare growth in six Eastern European states that joined the EU to growth in Russia and three others, including Ukraine, which failed to do so. Back in 1990, the average per capita GDP in each group was 44% of per capita GDP in the Eurocurrency zone. By 2019, among those who joined the EU, per capita GDP rose to 70% of the Eurozone level; but Russia and the other three actually fell further behind to just 39% of the Eurozone level. Moreover, among the six EU-joining countries, those which started off the poorest in 1990 did the most catching up. Relatively poorer Poland and Lithuania grew faster than the richer Czech Republic. While Czechia is still the richest, the gap is smaller.

By contrast, Russia’s recovery stalled out after 2013. Whether coincidentally or not, that’s during the same period when Putin shifted from focusing on economic recovery to recreating the Russian/Soviet empire. Out of 15 post-Communist countries, Russia suffered the third lowest growth in per capita income during 2013 19, just 0.5% per year versus an average of 3% for the rest. The only countries worse off were Moscow’s Belarusian satellite and the victim of its aggression: Ukraine.

Why does integration with the EU countries, and eventually full membership in the EU, make such a difference for Ukraine? For one thing, while the EU has created association pacts with non-members as part of a transition, full membership requires that countries meet certain standards called the “Copenhagen criteria.” The latter promote not only the rule of law, certain democratic norms, and anti-corruption measures, but also market-oriented economic reforms that promote growth and eventual adoption of the Euro currency. Countries typically take several years to make themselves ready.

While Putin’s predecessor, Boris Yeltsin, once spoke about Russia joining the EU, Putin has never wanted to do so, complaining that it would entail EU interference in Russian affairs. Instead, he organized the Eurasian Economic Union, whose only members are countries formerly absorbed within the Soviet Union or else Russia’s satellite countries.

Along with economic and political modernization, EU membership also entails genuine integration into the single market through greater volumes of trade and foreign direct investment (FDI). The latter refers to a foreign firm setting up operations on a country’s soil or else buying a controlling stake in an existing firm. It’s not volatile “hot money” flows. It’s been long established that countries grow faster if they higher levels of trade and inward FDI. That’s partly because trade and inward FDI introduce modern technologies and new management strategies, and partly because they increase the force competition.

On the trade side, in the six post-Communist EU members we’ve been looking at, the ratio of trade (exports plus imports) to GDP averaged 70% in 1990. By 2019 it had nearly doubled to 130%. The cumulative stock of inward FDI has mushroomed from a negligible amount in 1990 to 60% of GDP as of 2020.

Over the years, Ukraine has gradually reoriented both its economy and overall society away from Russia and toward the countries of the EU. In one telling move, in 2019, a newly established Orthodox Church of Ukraine received permission from the Patriarch in Istanbul to become independent, rather than remain under the sway of the Russian Orthodox Church.

On the trade side, Ukraine reoriented toward the West. The peak value of Ukraine’s trade with Russia came in 2011 at $49 billion. By 2020, it had plummeted to just $7.2 billion. By contrast, in 2021, trade with the EU totaled to more than $58 billion. When Russia dominated Ukraine’s trade, Ukrainians served as “the hewers of wood and drawers of water,” i.e., primarily exporting agricultural goods, energy products and basic metals, along with some machinery. As with other countries, trading more with the EU will upgrade Ukraine’s exports to more knowledge-intensive items, thereby helping the entire economy upgrade. That’s what will raise living standards.

FDI is also playing a big role in the economic upgrade. The stock of inward FDI rose from a negligible level in 1990 to 32% of GDP by 2020. The top investors were the US at 20% of all FDI, followed by Germany, and the UK. Russia does not even show up in the top ten. Importantly, half of this investment has come in the fields of software, renewable energy and logistics. Full EU membership will further increase both FDI and trade and therefore accelerate modernization.

To the Ukrainian people, prosperity, democracy, independence and becoming part of today’s Europe community are not separate goals but indivisible threads in one tapestry. This attitude became manifest back in 2004, when Yanukovych tried to steal the Presidential election. People took to the streets in peaceful protests that became known as the “the orange revolution.” They forced a revote which Yanukovych lost (he did win six years later). Putin convinced himself that the “orange revolution” reflected not genuine popular feeling but the machinations of Western intelligence agencies. He suffered the same delusion regarding a “rose revolution” against pro-Moscow rulers in Georgia a year earlier. This self-delusion is why Putin completely failed to anticipate how strongly Ukrainians would resist this year’s attempt to conquer them.

No wonder Putin sees Ukraine as a threat. If the Ukrainian people can create a prosperous liberal state, Russians might start asking: why not us.