There only new thing in Vice Finance Minister Koji Yano’s that Japan’s budget deficits were like “the Titanic heading into an iceberg,” was that he harshly criticized the elected government in the prestigious Bungeishunju magazine rather than in private briefings.

For nearly a half-century, ever since 1978 when the Ministry of Finance (MOF) said Japan would “collapse” unless it created a consumption tax and ended deficit spending, the MOF has been scaring Prime Ministers into heeding its diktats.

These days, the allegedly inevitable outcome is a crash in the government bond market. Officials have even joked in private about how many Prime Ministers the MOF had to “sacrifice” in order to create the consumption tax and then repeatedly hike the rate.

If the Ministry’s warnings were accurate, it would have been serving the nation. In reality, it has been repeatedly, lengthily, and stubbornly wrong. To be fair, the MOF’s views are shared by many well-respected economists. In 2012, two of them predicted that, without a consumption tax at 15-20%, markets would crash sometime between 2020 and 2023.

The MOF’s Track Record

Let’s look at the record.

Back in the mid-1990s, the MOF convinced Prime Minister Ryutaro Hashimoto to raise the consumption tax from 3% to 5%, which would have been no problem for a healthy economy. Unfortunately, as Washington warned, Japan’s health had been sapped by the growing mountain of bad bank debt. Sure enough, the April 1997 tax hike sent the economy into a severe recession, which greatly magnified the banking crisis, further deepening the recession.

When Treasury Secretary Robert Rubin urged a rollback to 3% in a private meeting with Finance Minister Kiichi Miyazawa, Liberal Democratic Party (LDP) Secretary General Koichi Kato lashed out. “You have no idea how many Prime Ministers were sacrificed...to introduce the consumption tax...These comments are extremely offensive.”

Months later, Hashimoto joined the list of sacrifices when the LDP suffered an unexpected rout in the Upper House elections, and he had to resign. The MOF, too, was punished for its failures on the budget and bank debt. Because the opposition now controlled the Upper House, the government had to acquiesce to ending MOF control over banking issues to secure agreement on a bank bailout.

Fast forward to 2010 when the Democratic Party of Japan (DPJ) was in power under Prime Minister Naoto Kan. To solidify its rule, the DPJ simply needed to win that summer’s Upper House election.

However, the MOF persuaded Kan that, without another hike in the tax, Japan could suffer a debt crisis like the ones then hitting Europe. In reality, the only European countries wracked by capital flight were those with “twin deficits,” i.e., both domestic government debt and massive foreign debt. No country experienced a crisis if, like Japan, it enjoyed an international surplus.

Nonetheless, a frightened Kan campaigned on raising the tax. No wonder the DPJ lost. Then, in 2012, just months before a Lower House election, Kan’s DPJ successor passed a law to double the tax to 10% by 2015. Not surprisingly, the DPJ lost in a landslide. When the first stage of the tax hike in 2014 depressed the economy, LDP Prime Minister Shinzo Abe defied the MOF and delayed the second hike for a few years.

Other victims of the MOF’s bad advice were all the investors who repeatedly bet on a JGB price crash and who repeatedly lost big. Betting on a JGB crash became known as a “widow-maker.”

Slashing Pensions and Healthcare for the Elderly

Because the economy has become overly dependent on repeated injections of fiscal stimulus to make up for weak private demand, the MOF has been unable to impose as much fiscal austerity as it wanted. Still, spending cuts have been tougher than many realize, especially on the elderly.

The MOF argues that, on its current path, aging will compel the government to spend larger and larger portions of GDP on social security and healthcare. The numbers tell a different story. Outlays for the elderly rose until they hit a peak of 12.5% of GDP in 2013, and then they flattened. The figure was 12.4% in 2019. How did this happen?

As pointed out by Professors Mark Bamba and David Weinstein, even though there were more elderly, the government cut spending per senior. An update of their numbers shows that social security per pensioner plunged by a fifth from its 1996 peak of ¥1.92 million ($17,000) to just ¥1.49 million ($13,200) in 2019. Healthcare was slashed by 15% from ¥520,000 ($4,600) in 1999 to ¥440,000 ($3,900).

These cutbacks are one of the reasons that, among women over age 65 living alone, the poverty rate has risen to almost half. In 2018, 45,000 seniors were arrested—it was 7,000 in 1989—mostly for shoplifting and usually just ¥3,000 ($26) worth of items. Most are not jailed, but a third of all people in prison for shoplifting are over age 60, up from 5% back in 1960. A few spend a year or two in prison, get released, and then shoplift again, just so that they can go back to a place with a bed, meals, nursing care, and company.

If these cuts continue, spending on seniors could actually decline as a share of GDP. That’s because the rise in seniors is flattening out. From 1994 to 2019, the number doubled from 17.6 million to 35.5 million. Going forward, the rise will decelerate, peak at 39.4 million in 2043, and then fall back again. Moreover, as Bamba and Weinstein point out, the increase in seniors is more than offset by a big decline in the number of young people, which means a big cut in spending on education and childcare.

BOJ Buys JGBs, Slashing The Odds of a Crash

None of these facts have prevented the MOF from singing the same old song. In its fiscal 2021 Public Finance Fact Sheet, the MOF approvingly cited an IMF study that contended: “To finance aging costs, the consumption tax rate would need to increase gradually to 15% by 2030 and to 20% by 2050 [compared to an OECD average of 19%--RK]...Without meaningful change to pension, health, and long-term care spending, fiscal sustainability may remain out of reach.”

The reasoning offered by the MOF offers sounds plausible: the ratio of government debt to GDP keeps mounting; that cannot go on forever; eventually, investors will panic.

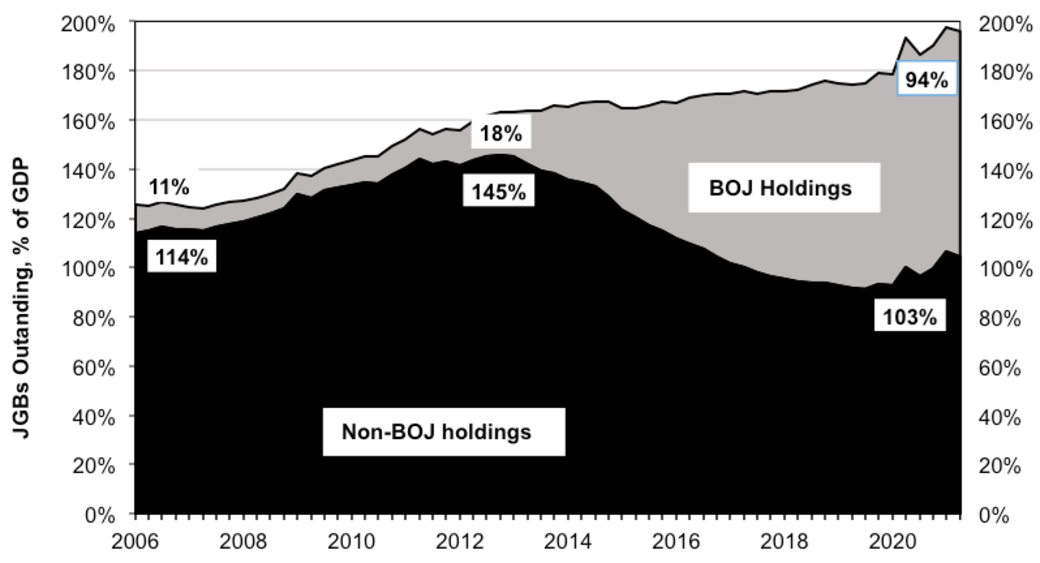

The problem is that the MOF is talking about “gross” government debt (mostly JGBs), which increased from 70% of GDP in 1990 to 237% in 2020. That, however, is a meaningless number because it includes debt that one government agency owes to another. The Bank of Japan (BOJ) is not about to dump JGBs. What really counts is the “net” debt, i.e., the debt held by private investors, and that has plummeted since Haruhiko Kuroda became BOJ Governor in 2013.

In the name of fighting deflation, the BOJ has bought up almost half of all JGBs, an amount equal to 94% of GDP. That’s up from just 18% in 2012. By contrast, JGBs owned by others, mostly private investors, tumbled from 145% of GDP in 2012 to 103% today (see chart).

Moreover, what really triggers bond crises is not the size of the debt per se. Capital flight breaks out when the government can no longer pay the interest bill. Japan has no such problem. In 2021, because the BOJ pushed interest rates to the cellar, interest payments were down to just 0.4% of GDP. That’s negligible compared to the peak of 1.9% almost 40 years ago. If Japan did not suffer a crisis when both privately-held debt and the interest bill were so much higher, why should it suffer one now?

The MOF answer is that interest rates will not stay low forever. When they inevitably rise, then comes the crisis. Again, it sounds plausible, but it defies Japan’s experience. The BOJ has proved it can keep interest rates super-low, as it has done for more than a quarter of a century. Since Japan does not need to borrow from the rest of the world, it can control its own interest rates. Would the BOJ really allow a financial cataclysm rather than continuing to flood the system with money if necessary?

Not Crisis, But More Corrosion

No one denies that Japan’s chronic deficits have consequences. The impact, however, is not a JGB crash but continued slow corrosion of the economy. That difference in diagnosis requires a very different prescription.

First, the deficit itself is not the cause of Japan’s economic maladies, but rather a symptom of weak private demand. So, the first priority is to address the root causes of that weak demand, which are the sluggishness of real wages and cash hoarding by corporations.

The deficit is also a product of weak growth in GDP and therefore in the tax base. In any country, GDP depends on the number of workers and their productivity, i.e., GDP per worker. If the number of workers grows 1% and output per worker by 2%, then GDP will grow 3%. In Japan, the working-age population will shrink 1% a year over the next two decades. But Japan can make up for this with better productivity. Since 2000, GDP per work-hour has risen just 1% a year, half the 2% rate in the 1990s.

Restoring 2% productivity growth would provide the same boost to GDP as if there were no decline in the number of workers. Can this be done? Yes. Japan’s productivity is currently 25% below the rest of the Group of Seven countries. So, undertaking structural reforms that enable Japan to catch up to world benchmarks could boost productivity in a big way.

Effective reform requires that taxes, spending, and other policies be harmonious with growth, so as to expand the tax base. There are some countries where a consumption tax is fine, but Japan is not one of them. That’s because it makes weak consumer demand even weaker. Other, better taxes are available. On the spending side, paving over riverbeds and providing credit guarantees for zombie companies not only depresses growth but make the public distrust any kind of tax increase since it feels the money would be wasted.

Finally, the chronic deficits increase pressure on the BOJ to maintain its ultra-low interest rate policy and, while it’s necessary now, prolonging that indefinitely weakens the economy’s foundations. For example, 36% of all bank loans now charge less than 0.5% interest, and 17% less than 0.25%.

These negligible rates keep zombie companies in business, and that hurts other, healthier companies, thereby dragging down GDP growth. Interest on deposits used to provide seniors a big chunk of their income. Not today.

If you put down ¥10 million ($88,000) on a time deposit of a year, your interest will be just ¥1,000 ($8.85), enough for a ham & bologna sandwich plus a large caffe mocha at Doutor. No wonder that 40% of retirees’ household spending each year comes from drawing down their savings. How many will run out of savings before they run out of years?

Better growth will not solve all the budget problems, but it would make them far more manageable. On the other hand, undertaking tax hikes and spending cuts without structural reform will make the budget problems even worse.