The following article is based on the online series, "Jissen! Tsutawaru Eigo Training" by Katsuyoshi Hakoda (Instructor and Coordinator of English Language Education, AEON). Click here to read the original article in Japanese.

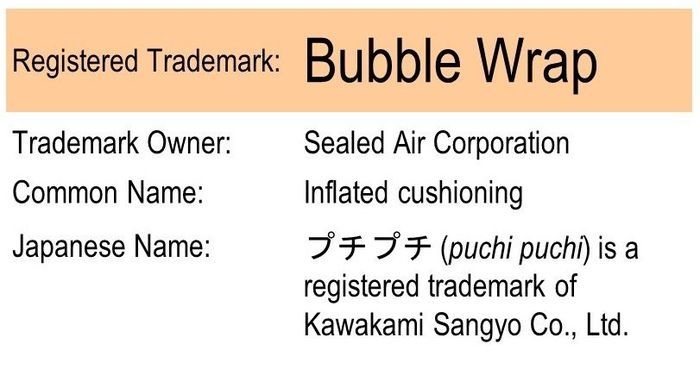

“Puchi puchi… How do we say puchi puchi in English?” Hakoda-sensei wondered aloud while writing a dialogue for one of his eikaiwa materials. “Oh, right. It’s bubble wrap.”

Overhearing Hakoda-sensei’s mumbling, his co-worker John chimed in with a word of advice: “Don’t forget to capitalize it—it’s trademarked, you know.”

Though he had heard and used this word for many years, it wasn’t until this point that Hakoda-sensei realized that “Bubble Wrap” was a registered trademark.

He paused. “OK,” he thought. “So, what’s the generic term for Bubble Wrap?”

In this month’s article, Hakoda-sensei introduces a variety of English and Japanese brand names that are commonly used as general terms. This is called a proprietary eponym, or, more simply, a generic trademark.

Like “Bubble Wrap”, the two languages are riddled with names of things that are often thought of as generic but are actually registered trademarks. Whether you’re using them in your mother tongue or adding them to your second-language vocabulary bank, it’s worthwhile to recognize the legal status of these popularized terms.

So what is the generic name of Bubble Wrap?

“Inflated cushioning.”

Unless you’re citing shipping details as part of some official documentation, no one would ever refer to that bubbly plastic packaging material as “inflated cushioning”. Bubble Wrap is one of many trademarked names that are used by consumers in a generic sense but are still legally protected.

However, this isn’t always the case. Some terms were originally legally protected trademarks but have since lost their legal status due to widespread use. Still others were abandoned and have become available for use as a generic term. In some instances, genericized names were thought to be trademarked by a specific company but it was later revealed that the name was never registered for protection in the first place.

In Japan, words such as “sunny lettuce” (romaine lettuce), “home theater” (home cinema) and “hotchikisu" (stapler)are examples of words that were once trademarked but are no longer legally protected.

“Sunny Lettuce”: Trademark Erosion

According to some sources, the “sunny lettuce” was named after a vehicle that was popular at the time: the Nissan Sunny. However, in June 2002, Takii Shubyo Shuppan-Bu’s Engei Shin-Chishiki (Horticultural Knowledge) published an interview with Mr. Akiyoshi Asakura, who popularized romaine lettuce in Japan. He stated, “the name comes from the sun which nourishes and gives the leaves their beautiful red color."

Trademark registration for “Sunny Lettuce” was first applied for in 1982, but was rejected by the Japan Patent Office (JPO) in 1985. The reason, according to the JPO website, was that ‘Sunny Lettuce’ had become too closely associated with lettuce itself, making it indistinguishable from other similar products (Trial No. 2936 of 1982, August 6, 1985). This is a classic case of trademark erosion, whereby a brand name becomes genericized through constant use, thus losing its legal protection as a trademarked term.

“Home Theater”: Abandoned Trademark

The term “Home Theater” was registered as a trademark in 1963 by Yaou Electric Co. (current name: Fujitsu General). According to a press conference held by Fujitsu General in 1999, the company decided to make the name “home theater” available to everyone. This decision was based on the company’s wishes to make “home theater” a ubiquitous term with hopes of fueling the growth of the home entertainment system industry.

“Hotchikisu”: No Records Found

The stapler was first imported from the U.S. by Ito Ki Shoten (now Itoki Co., Ltd) in 1903. According to their website, both the “Hotchikisu” and “Zem Clip” (paperclips) were first imported to Japan at the same time and were trademarked by Ito Ki Shoten.

However, in an article by Nikkan SPA! Magazine, Mr. Takashi Konoue contacted Itoki directly to inquire about the trademark status of the stapler and paperclip. According to a customer service representative, there exists no official record of the company ever trademarking or allowing those trademarks to expire. Whether or not it was actually trademarked remains a mystery...

Genericized U.S. Trademarks

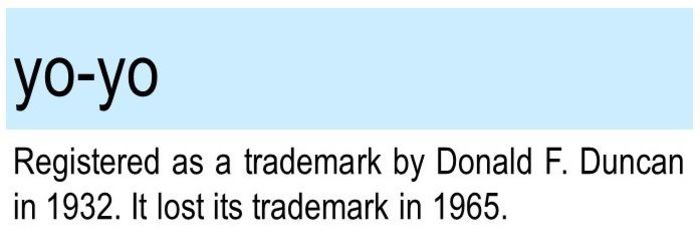

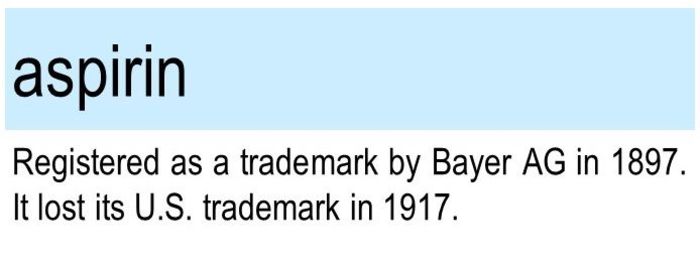

Let’s take a look at similarly genericized trademarks from the U.S. First, we’ll start with genericized terms that were once product names but have become common and are now freely available to everyone.

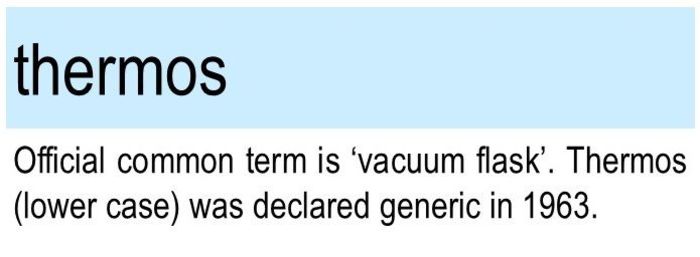

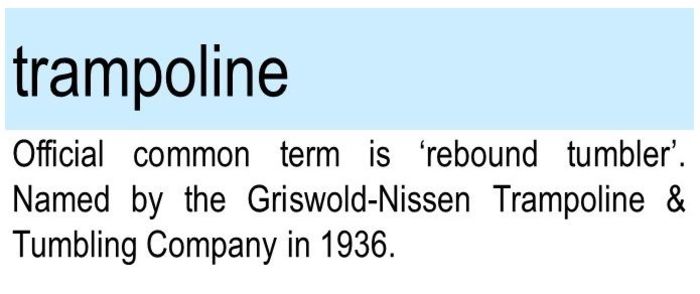

It’s interesting to learn that many commonly used words like “escalator” and “dry ice” were once trademarked brand names. They’ve become so ubiquitous that hearing them referred to by their official common name sounds downright unnatural. You’d never say “My kids love playing on the rebound tumbler” or “I have some tea in my vacuum flask”. You could, but people will look at you funny.

The words listed above are all examples of product names that are no longer trademarked in the U.S., but they may retain legal protection in other countries. Still, it’s nice to know that they have become so common that we no longer need to worry about capitalizing these words.

Trademarked Words Commonly Used in Japan

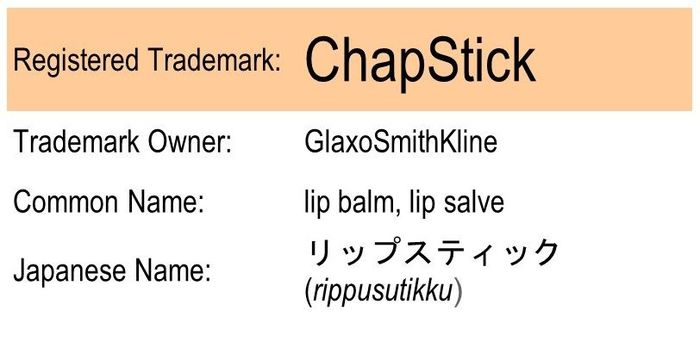

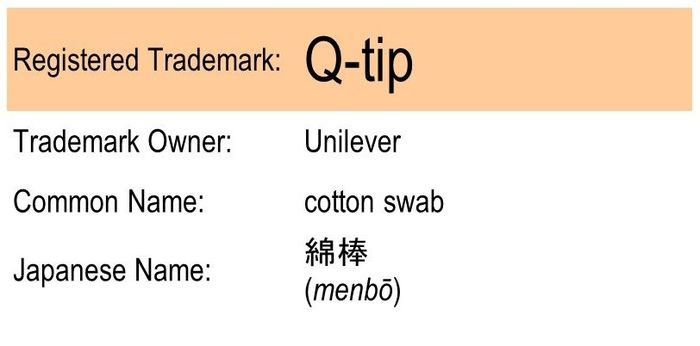

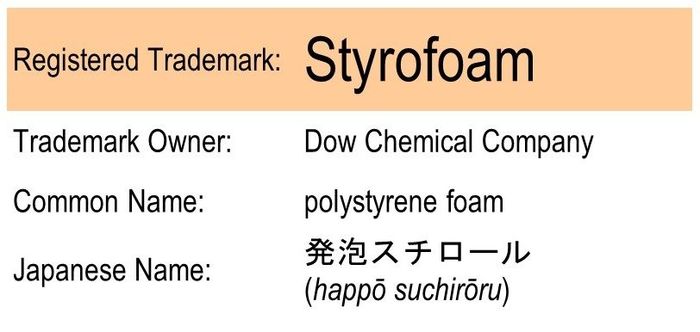

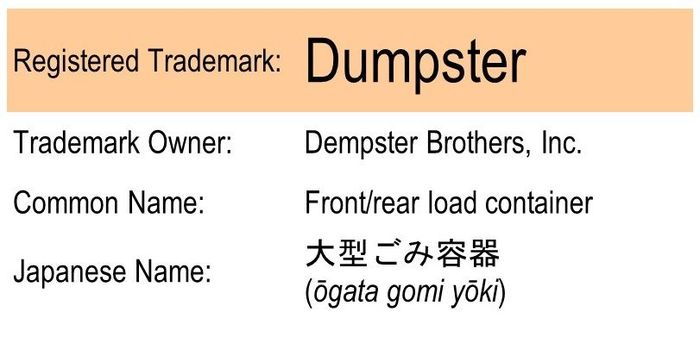

The following are a list of words that are registered trademarks but are often used as common terms. Because these are brand names, they must be capitalized when written out. Hakoda-sensei has also included the official common name below each trademark. We’ve become so accustomed to using the trademarked names that referring to them by their official common names seem counterintuitive.

Let’s begin by looking at trademarked names that are popular here in Japan.

Most of these product names are commonly used and trademarked here in Japan. Looking over this list, it’s easy to tell how these products got their start as distinguishable consumer goods. It’s interesting to note that when translated into Japanese, ‘Jacuzzi’ became ‘Jagujī’. Perhaps it’s similar to the way ‘avocado’ is sometimes pronounced ‘abogado’ in Japanese.

An official Japanese common name for Hula Hoop could not be found. フープ (fūpu) by itself might suffice. Rhythmic gymnastics uses apparatus (手具; shugu) such as a ball, a hoop and clubs. The Japanese name for these hoops is 手具輪 (shuguwa), but this is probably a term specific to rhythmic gymnastics.

Trademarked Words Commonly Used in English

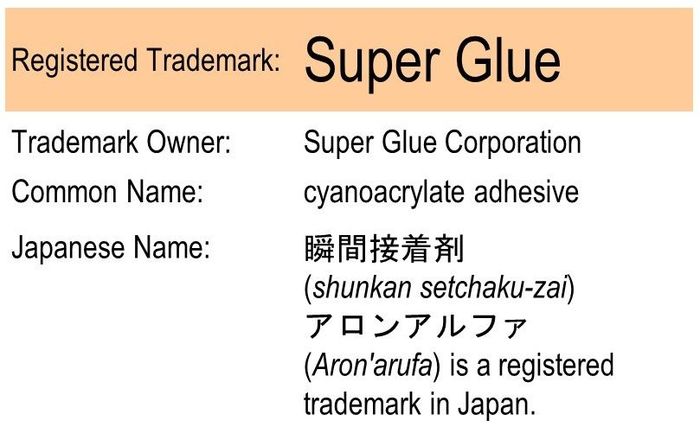

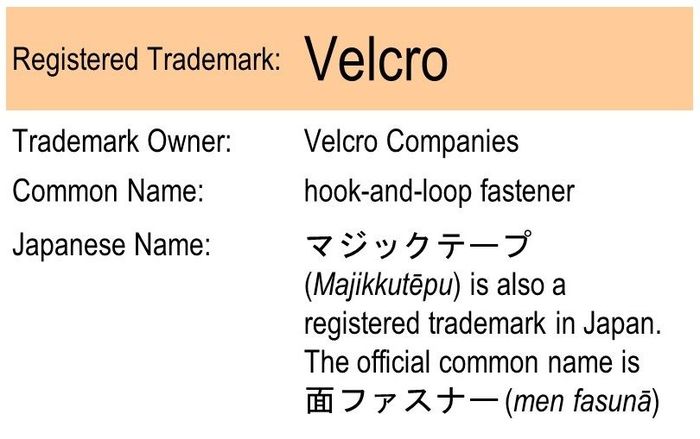

Next, let’s look at registered trademarks that have morphed into an entire product category. Hakoda-sensei has also lined up the Japanese names along with the English trademarks.

Generic trademarks are all over the place and people use these terms often not realizing their connection to a specific trademark holder. But if you want to avoid infringing on intellectual property rights, you’ll need to steer clear of words like “Styrofoam”, “Q-tip” and “Dumpster”. The problem is, not everyone will know what you’re talking about when you say, “polystyrene foam”, “cotton swabs” or “front load containers”.

Is Puchi Puchi a Registered Trademark?

Hakoda-sensei’s co-worker John asks, “So, what do you call Bubble Wrap in Japanese?”

“プチプチ (puchi puchi)” said Hakoda-sensei matter-of-factly.

“Is that a generic term?”

So back to the internet he went. While he couldn’t find a direct translation for “inflated cushioning,” he did find the following translations of the world “Bubble Wrap”: プチプチ (puchi puchi), エアキャップ (eakyappu), バブルラップ (babururappu) and …気泡緩衝材 (kihōkanshō-zai)!

And so it turns out that Puchi Puchi is a trademarked name! Although not as well-known, other inflated cushioning brands exist such as エアキャップ (Eakyappu), ミナパック (Minapakku) and キャプロン (Kyapuron). The Japanese common name, 気泡緩衝材 (kihōkanshō-zai) is a perfect translation of “inflated cushioning”. But like its English counterpart, inflated cushioning, no one will comprehend you when using the term kihōkanshō-zai. When copyrights aren’t really an issue, we’re probably fine using “Bubble Wrap” and “Puchi puchi”.

What do you think?