In the halls of the Prime Minister’s Office and the Foreign Ministry, it is popular to express anxiety about the future of relations with the U.S. under a new Biden administration. Fed by the conservative media in Japan, officials and ruling party politicians revive familiar claims that Democrats are ‘anti-Japan’ and ‘pro-China,’ or even worse, ‘pro-Korea.’ Some see evidence of this in the RUMORED appointment of Susan Rice as Secretary of State, while others point to former President Barack Obama’s cool relations with then Prime Minister Abe Shinzo.

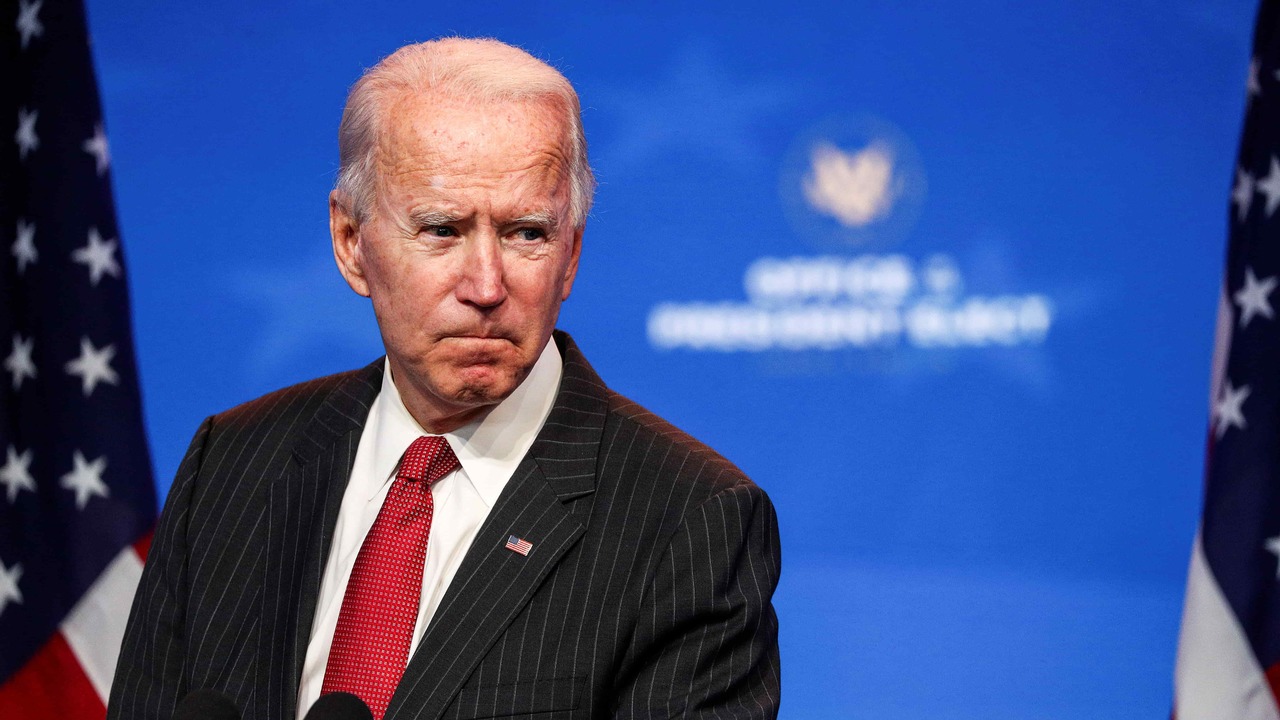

Interviews with former senior Obama administration officials from the State and Defense departments, as well as current Biden advisors, most of whom preferred to speak on a background basis due to the sensitivity of the transition, paint a very different picture. President-elect Biden will bring to the White House not only his experience as Obama’s Vice President for eight years, but even more importantly, 36 years in the U.S. Senate, where he twice chaired the Foreign Relations Committee. Biden is a consummate politician, sensitive to the limits on foreign policy imposed by domestic politics but also confident in his ability to use personal relationships to shape foreign relations.

The Vice President draws upon his own experience of personal tragedy – the death of his first wife and daughter, and later of his son Beau – and his sense of history, derived in part from his Irish heritage. He brings to foreign policy “a sense of Greek tragedy but also of the importance of individual destiny,” says a senior Democratic party Congressional aide. “He believes in personal diplomacy, in a way that Obama did not and that Donald Trump never did for reasons of lack of empathy.”

Based on his experience in the Senate, and as Vice President, the Congressional aide describes him as “fluent in Asian style diplomacy.” Biden, he adds, “is a true believer in alliances. That is a deep fiber of his being.” For the incoming administration, alliances are central to their major goals – crushing the pandemic, tackling climate change, and restoring economic growth.

Biden’s views on the centrality of alliances were shaped by the Cold War and his early focus on the Soviet Union and on the role of the NATO alliance. Though he was placed on the Foreign Relations Committee by Senator Mike Mansfield, who later served as Ambassador to Japan, Biden has mostly been a Western Europe centered politician. When it comes to Asia, however, Biden has been influenced by longtime aides who see Japan as the most important U.S. partner.

Biden in action – the Asia swing of 2013

Biden’s trip to Japan, China and South Korea in December 2013 offers a unique window onto his views. The Obama administration was looking to deepen its ‘pivot’ toward Asia and, as a key part of that strategy, conclude negotiations to form the Trans-Pacific Partnership. Hopes for a close partnership with China were fading as the Chinese flexed their military muscles in the East and South China Seas. Meanwhile, North Korea conducted it third nuclear test in February, along with numerous missile tests.

The U.S. was eager to bring Japan and South Korea into closer security cooperation, tightening trilateral coordination as a counter to China. There was growing concern about South Korea drifting into the orbit of China, propelled partly by the election of conservative President Park Geun-Hye who was eager to improve ties with Beijing.

Park was deeply uneasy with Abe, who had come to power in December 2012. The conservative Japanese leader had signaled his intention to roll back previous Japanese government statements on wartime history, particularly the Kono statement on Comfort Women and the Murayama statement on the war issued in 1995. By the fall of 2013, relations were almost entirely frozen.

In November, China announced the establishment of an “East China Sea Air Defense Identification Zone,” covering most of the airspace of the sea, including territory administered by Japan, South Korea and Taiwan. China’s provocative move was at the top of Biden’s agenda when he arrived in Tokyo on December 2, making the need for trilateral security cooperation even more urgent.

“We believe that Northeast Asia will be strongest when its two leading democracies work together to meet common threats, and when the three of us – the United States, Japan, and the Republic of Korea – work together to advance common interests and values,” Biden told the Asahi ahead of his trip.

Privately, Biden pressed Abe on the need to reach out to Park and hold a summit to break through on relations. He left that meeting convinced that Abe was ready to meet.

His decision to get engaged in this effort was made against the recommendation of his advisors, according to a former senior State Department official who was based in the region.

“We wanted the Japanese and Koreans to do a better job of getting along,” the official told me, “but we didn’t recommend that Vice President Biden jumps into that issue.” American officials were pleased with Abe’s stance on alliance issues, particularly the TPP. “But the one low mark he was getting from the U.S. was on history issues,” the official explained. Still, American diplomats were wary of getting in the middle of history issues, fearful that it would only anger both sides. “But Biden was a confident American politician,” said the official, believing that his personality “might make a difference.”

Biden went next to China and spent some five hours in talks with Xi and other Chinese leaders, pushing back on the ADIZ declaration and pressing the Chinese to improve ties with Japan and South Korea. They also spent considerable time talking about North Korea, with Biden hoping to win Chinese help to bring Pyongyang back to the bargaining table.

The last stop was Seoul, on December 6-7, where Biden and Park had a somewhat difficult conversation. They spent a lot of time talking about defense cost-sharing with Biden pressing the Koreans to do more. Biden told Park that Abe was ready to meet, putting pressure on her to agree to a summit.

“There is a growing frustration in Washington without assigning blame to Park,” a senior American diplomat told me and a small group of Stanford visitors two days after Biden left Korea. “We may get historical issues, but we still think these countries should get along.”

When I and my Stanford colleagues met Park, the Korean leader was visibly upset about the squeeze being put on her by Biden. The Koreans clearly felt the Americans had misread Japanese intentions. She took office prepared for cooperation with Japan, Park told us, but Japanese officials, including deputy Premier Aso Taro and Abe made statements that either ignored or sought to revise the previous Japanese positions on history issues.

“I am not closing the door to a meeting and dialogue is important,” Park said. “But it is important that for a summit to be successful, Japan should not be glossing over these issues.” It would be worse, she continued, if Abe were to emerge from a meeting and make controversial statements about the past or even visit the Yasukuni shrine to the war dead. Park spoke passionately about the problem of the surviving Comfort Women. “They will not live much longer,” Park told us. “This issue involves more than just these women. It involves the human rights of women in wartime. We cannot afford to see Japan deny responsibility for such a grave issue.”

Park insisted that a summit had to be based on a firm commitment from the Japanese government to confirm the validity of the Murayama and Kono statements and refrain from any provocative actions. It was a message, U.S. Embassy officials told us, she had conveyed very clearly to Biden.

Evan Medeiros, the NSC official and Asia expert who accompanied Biden on this trip, insisted that the Vice President “didn’t try to mediate between Japan and Korea,” as he put it to me. “He raised issues about history with both Park and Abe and encouraged both to be flexible and reasonable.”

The Yasukuni crisis

Some days later, Biden held a long phone call with Abe, briefing him on his trip and his discussion with Park. He had pressed Park to meet, Biden told Abe, but she was worried about what might happen afterwards. Abe did not make any firm commitments in the call, but U.S. officials, and Biden himself, were left with the clear impression that Abe would not visit Yasukuni shrine or take other actions that might undermine the attempt to hold a summit.

Biden’s efforts came crashing down when, to the surprise of the Americans, Abe visited Yasukuni shrine on December 26. “Biden inserted himself and it didn’t work,” the former senior State Department official told me.

When the news hit Washington, it was Christmas day and the White House, with Biden’s involvement, authorized the Embassy to issue an unusual statement expressing “disappointment” (失望)with Abe. “What Abe said and what Biden heard might have been different things,” the former official admitted. “I think the entire U.S. government was pissed off at Abe. Japanese were shocked and were really worried. And that was the intended impact.”

Despite that moment, however, Biden did not come away with any grudges, the senior official told me. Instead, Biden, with the President himself now engaged, pressed ahead. In March 2014, Obama hosted Park and Abe at a trilateral meeting on the sidelines of a nuclear security summit in the Hague, trying to use North Korea as a way to bring them together. In April, Obama visited both Japan and South Korea and took his own stab at addressing the history issues, carefully avoiding them in his public statements in Tokyo while openly acknowledging the pain of the past in Korea.

The next year, Abe and Park made separate visits to Washington. Abe tried to meet American concerns by toning down his statement on the 70th anniversary of the war. When Park visited in the summer, Biden had a long lunch with her at the Vice President’s residence. He talked about Ireland and why history matters.

“Biden clearly understands the history issues,” a former senior Obama official who was directly involved in these talks told me. “What makes him unique is that he understands them from a policy standpoint but he also gets it as a politician. It is a political issue and it takes somebody at the leader level to understand the contours of this. It is not pressuring. It is understanding that it is important to the United States.”

The meeting had an impact, the former official believes. “There was some Biden magic,” he said. Park left that meeting and delivered a speech where she declared she was ready to meet Abe. The two leaders finally got together in November, on the sidelines of a trilateral summit with China, leading to a breakthrough in the long-stalled talks on a Comfort Women agreement, finally announced that December.

Biden and Suga – a match?

Today, we are at a similar moment. The incoming Biden administration will have to forge a new approach to China, but its priority will first be to strengthen alliances. Once again, the tensions between Japan and Korea stand in the way. But Abe is gone and the Koreans are apparently seeking a way out of the history impasse.

Does that mean Biden will personally get involved? Most Biden advisors believe he will empower others to act – probably Tony Blinken, likely to be Secretary of State. During the Obama administration, Blinken forged a vice-ministerial level trilateral coordination dialogue with Japan and Korea.

Personal diplomacy is likely to be essential, say Biden advisors. “Suga has a great personality for dealing with Biden,” says a former U.S. official who met him regularly. “In private, he has a good sense of humor, he can be garrulous, sharp and tough. He has a good chance of having a decent relationship with Biden.”

Biden advisors dismiss Japanese concerns about a ‘pro-China’ approach, or the role of Susan Rice. “I don’t think this matters,” one senior advisor told me. Whether the bureaucrats of Kasumigaseki believe that is another matter.