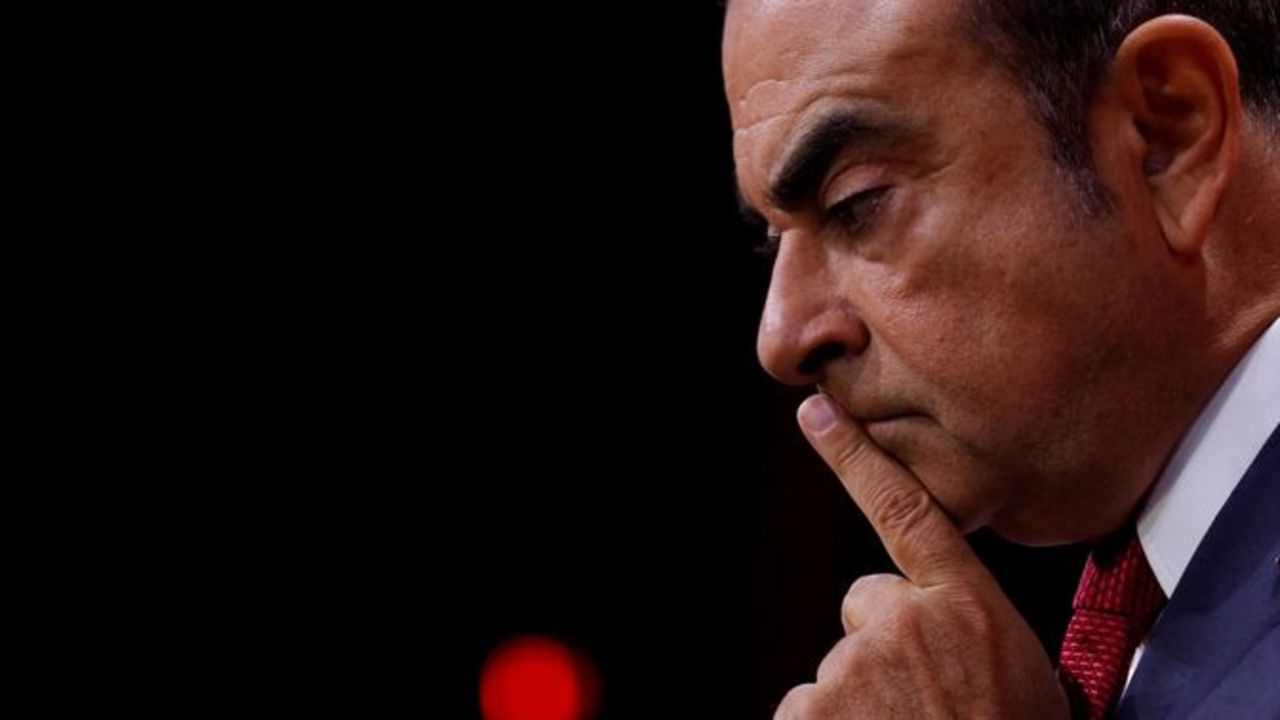

If allegations that former Nissan Chairman and CEO Carlos Ghosn failed to properly disclose his compensation are true, that immediately begs the question: Why? If he felt that the compensation was appropriate, then why not disclose it?

The most common answer offered in the burgeoning commentary on the Ghosn affair is that Ghosn and his colleagues were probably concerned that his compensation might be criticized due to local norms of equity. But are these really distinctively Japanese norms?

I think not. In fact, reformers in the United States and elsewhere are trying to crack down on excessive CEO pay in their own countries. And the voices for reform include bona fide capitalists as well as democratic socialists. Many feel that CEO-to-average worker pay ratios of 100 or 500 and more are both bad for business and bad for society at large.

The ratio of CEO compensation to median employee pay is 265 in the United States and 58 in Japan, with Britain at 201 and Germany at 136, according to data from Bloomberg and the International Monetary Fund.

If we do a back-of the-envelope estimate for Ghosn, his compensation was reportedly about 1 billion yen a year plus another 1 billion yen or so in the deferred compensation that was allegedly not reported. If an ordinary Nissan employee made 5 million yen, that would mean that Ghosn made about 400 times that employee. So his compensation is high, even by international standards.

But don’t effective CEOs deserve every penny? Let’s consider the case on its merits.

Those top executives with the highest compensation typically receive the bulk of that compensation in the form of stock options or other types of equity stakes. The theory is that this should align their interests with those of shareholders. In practice, however, stock options reward good financial performance but they do not punish bad performance or even fraud. They encourage executives to maximize short-term returns rather than long-term value, and to manipulate accounts to maximize nominal share prices.

Moreover, does annual compensation of 2 billion yen versus 1 billion yen really differ in any meaningful way? Wouldn’t each additional yen mean a lot more to regular workers than to the CEO? And would a CEO who demands that extra compensation really be more effective than one who does not?

Huge pay disparities represent a public insult to the workforce that can undermine corporate culture and erode worker morale. Nissan workers who were laid off under Ghosn have expressed their outrage publicly, but those workers still at Nissan must have their own misgivings as well. If the allegations are true, Ghosn not only breached laws and social norms, but he violated the trust of his own workers.

American legislators were sufficiently horrified by outsized CEO pay in the wake of the global financial crisis that they included a provision in the Dodd-Frank Wall Street Reform and Consumer Protection Act that requires corporations to disclose the ratio of CEO to median worker pay in reports to the Securities and Exchange Commission.

Meanwhile, British regulations on the disclosure of CEO-to-median employee pay ratios came into effect on January 1. Listed companies with more than 250 employees in the United Kingdom will have to disclose and explain these ratios. In addition, they will have report on how share price increases affect executive compensation, and how directors are considering employee and stakeholder interests when making management decisions.

Meanwhile, reformers in California are proposing a bill that would add a state tax surcharge for companies that pay top executives more than 100 times their regular employees.

Senator Elizabeth Warren submitted the Accountable Capitalism Act last year to tackle inequality in wealth and power in America more broadly. It would require large corporations to obtain a federal charter of corporate citizenship. Employees would elect 40% of board members, and executives would have to hold the stock shares they receive as compensation for at least five years.

These various reform efforts bring the issue to light and exert pressure on corporations to change. But there is a certain clunkiness to some of the specific remedies. They risk pushing companies to engage in even more accounting games to manipulate pay ratios. They set arbitrary cutoffs. And they may actually constrain companies from addressing the problem in a more meaningful way rather than in a pro forma fashion.

What would work better? This might be a tad idealistic, but I would suggest that a more effective remedy would rely on social norms and business practices to achieve a more equitable balance of reward for top executives versus average workers. That is, if dominant norms and practices dictated greater equity, then managers would adhere to these core principles without playing accounting games.

Now wait a minute. This utopian vision sounds a lot like – you guessed it – Japan.

Don’t get me wrong. I am not saying that all is well in Japan. For one thing, Japanese managers do not always adhere to Japanese ideals. Japan has bad actors, just like other countries, so it needs tough laws and stringent corporate governance standards to keep them in line. And Japan certainly needs further corporate governance reforms to tighten auditing standards, enhance transparency, and increase diversity in leadership.

But I am arguing that the erosion of traditional Japanese norms of economic fairness and management-labor solidarity in Japan should be lamented, not celebrated. Outsized CEO pay is not – and should not be – the global standard. Even most Americans would agree with that.