While Japanese reformers continue to advocate steps toward the U.S.-model of shareholder capitalism, some American leaders hope to move the United States in the opposite direction.

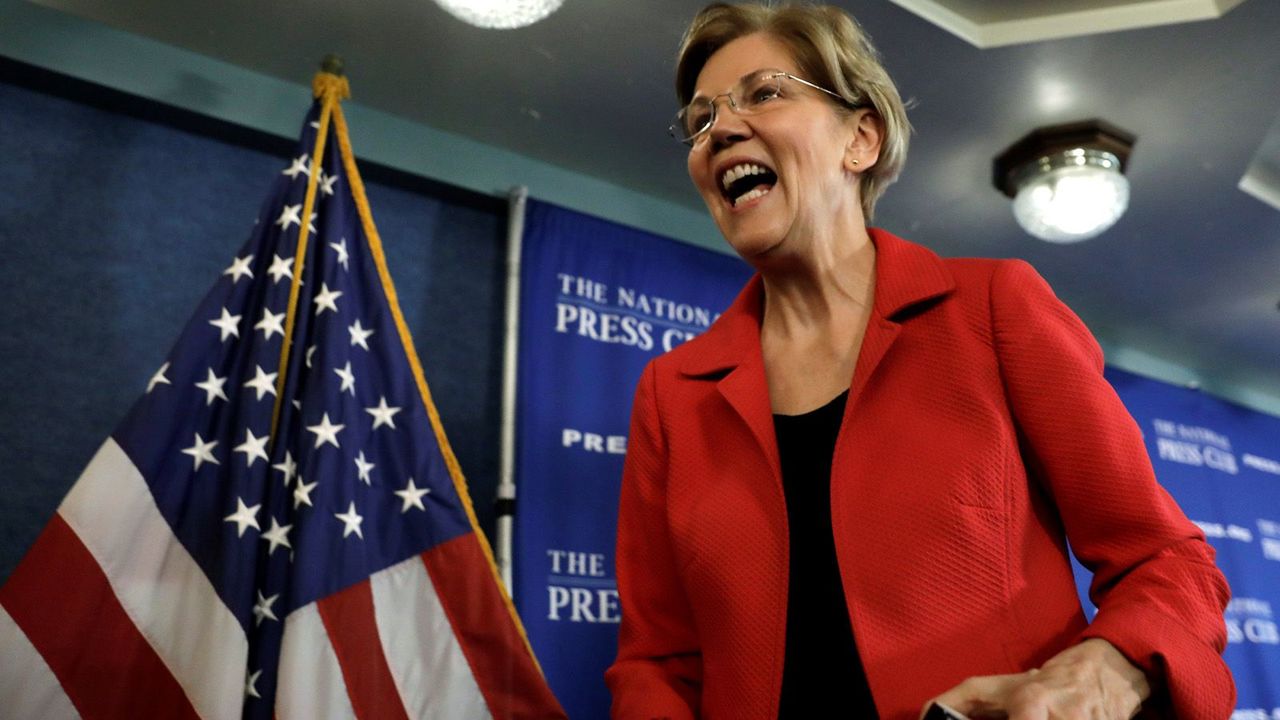

Most notably, Senator Elizabeth Warren, widely viewed as a leading contender for the Democratic nomination for president in 2020, recently proposed the Accountable Capitalism Act aimed at shifting the United States toward the stakeholder model often associated with Japan.

Warren framed the proposal as an effort to reverse the ascent of the shareholder model over the past three decades and to return to an earlier era when American corporations and workers thrived together.

Critics quickly dismissed the bill as wildly unrealistic, something that would never pass under this Congress or in this form. And they were right, of course. But they missed the larger point. Senator Warren has launched a substantive conversation about the deeper causes of inequality in wealth and power in America, and offered a first cut at some possible remedies.

The bill requires corporations with over $1 billion annual revenue to obtain a federal charter of corporate citizenship stipulating that corporate directors must consider the interests of all stakeholders, including employees, customers, and local communities as well as shareholders.

Employees would elect 40% of board members. Corporate executives would have to hold the stock shares they receive as compensation for at least five years, to encourage them to manage for the long term. Corporations would have to receive the approval of at least 75% of their shareholders and 75% of their directors to make political campaign donations. And the government could revoke a company’s charter if the company engaged in repeated and egregious illegal conduct.

Meanwhile, some on the left wing of the Democratic Party have gone further, branding themselves as “democratic socialists.” Senator Bernie Sanders of Vermont and Senator Cory Booker of New Jersey, both considered to be presidential contenders, advocate a jobs guarantee for all.

Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez, a congressional candidate from New York and a breakout media star, proposes Medicare for all, free college tuition, a universal jobs guarantee, and housing as a human right.

Sanders, Booker, and Ocasio-Cortez are right that the United States should provide universal health care insurance, as most other advanced industrial countries do. This would deliver better health care at a lower price, something all Americans should want. Beyond that, however, Warren offers the more promising approach.

She is focusing more on what I call “marketcraft” – the market governance that affects the distribution of wealth in the first place, rather than measures to redistribute wealth after the fact. In fact, I would argue that Warren’s bill should be folded into a broader marketcraft agenda that would include reforms to labor regulation, antitrust policy, and intellectual property rights that would promote greater economic equity as well.

Let me be clear: I support redistribution via a progressive tax system and welfare spending to improve the lives of all Americans. But the “marketcraft” agenda is even more fundamental than redistribution because it addresses inequality at its source.

In the current climate, it has the enormous advantage of being less costly in terms of budget dollars. And it would not provoke many Americans’ deep-seated mistrust of big government as much as calls for massive redistribution would. It does not strive to rig the economic system in favor of the poor and the under-represented, but simply to unrig it from favoring the wealthy and the powerful. In short, it offers an agenda that most Americans could support – if properly packaged.

Some of Warren’s critics charge that her proposals would undermine capitalism, but they would not. Corporations are granted certain privileges by law, such as limited liability, so it is only natural for the government to require that they consider public responsibilities in exchange for these privileges. And worker representatives on corporate boards would not prevent companies from serving their shareholders, but simply encourage “win-win” strategies to maximize shareholder returns by strengthening management-labor collaboration rather than by squeezing workers.

Academic studies have found that the core features of the shareholder model – including stock options, share buybacks, hostile takeovers, and independent directors – have not consistently improved the performance of American firms. Proponents of the shareholder value model believed that managers would more faithfully represent shareholder interests if their compensation were more closely tied to stock performance through stock options.

Yet in practice stock options reward managers for good performance but do not punish them for bad performance; they shift returns from shareholders to top managers; and they increase inequalities in compensation. Buyback programs divert resources from investment in productive capabilities and compensation for workers, so they undermine growth, job stability, and economic equality. Mergers and acquisitions are as likely to destroy value as to create it, especially for the acquiring firm. And outside directors do not necessarily improve firm performance either.

This leads me to a rather startling conclusion: Japanese policy makers and corporate executives have enacted many corporate governance reforms aimed at rewarding shareholders in the absence of clear evidence that these reforms would actually do any good.

I am not saying that Japanese corporate governance does not need any reform. Many Japanese companies would benefit from greater transparency, accountability, and diversity in their management systems.

To put this simply, there are two sides to corporate governance reform: improving management processes and fostering long-term growth, on the one hand, and increasing profits for capital at the expense of labor, on the other. Japan needs more of the former, and less of the latter.

So if some thoughtful Americans are rethinking the supposed virtues of shareholder capitalism, then perhaps Japanese should hold on to their healthy skepticism as well.