The effects of the so-called “Panama Papers” scandal have begun to ripple through Japanese business circles.

“I was surprised myself when our name was mentioned in the television news this morning,” said SoftBank Group CEO Masayoshi Son at a press conference held on May 10 to announce the group’s latest financial results.

The name of a SoftBank group company was included in the vast amounts of data leaked from a Panamanian law firm in April, which became widely accessible on May 10 via a different network.

In the press conference, Son did not go into detail about this news, simply explaining, “What I know so far is that it’s one of the sub-subsidiaries of our sub-subsidiary that invested in an offshore company established in one of those islands as a minor shareholder.”

The Panama Papers include over 11.5 million documents leaked from Mossack Fonseca, a Panama-based global law firm specializing in financial and legal advisory services for businesses interested in establishing offshore accounts and shell companies in tax haven countries.

On May 10, the data on these documents was instantly disseminated around the world via major global media. The information was added to a searchable and downloadable database called Offshore Leaks that has been managed by the International Consortium of Investigative Journalists (ICIJ) since 2013.

This data revealed approximately 214,000 corporate and individual names listed as clients of Mossack Fonseca, including prominent political figures like Iceland’s Prime Minister Sigmundur David Gunnlaugsson, who was forced to step down to quiet the growing public outrage over his family’s secret offshore bank accounts

Other clients linked with top political leaders included the late father of Britain’s Prime Minister David Cameron, relatives of China’s President Xi Jinping, and close associates of Russian President Vladimir Putin, who were revealed to have held undisclosed assets or owned offshore shell companies, among other past or ongoing secretive activities.

The Panama Papers scandal is capturing the attention of the international community, especially those who are keen to determine whether any of these clients’ financial dealings with Mossack Fonseca have been for illegal tax evasion.

400 Japanese companies and individuals were listed

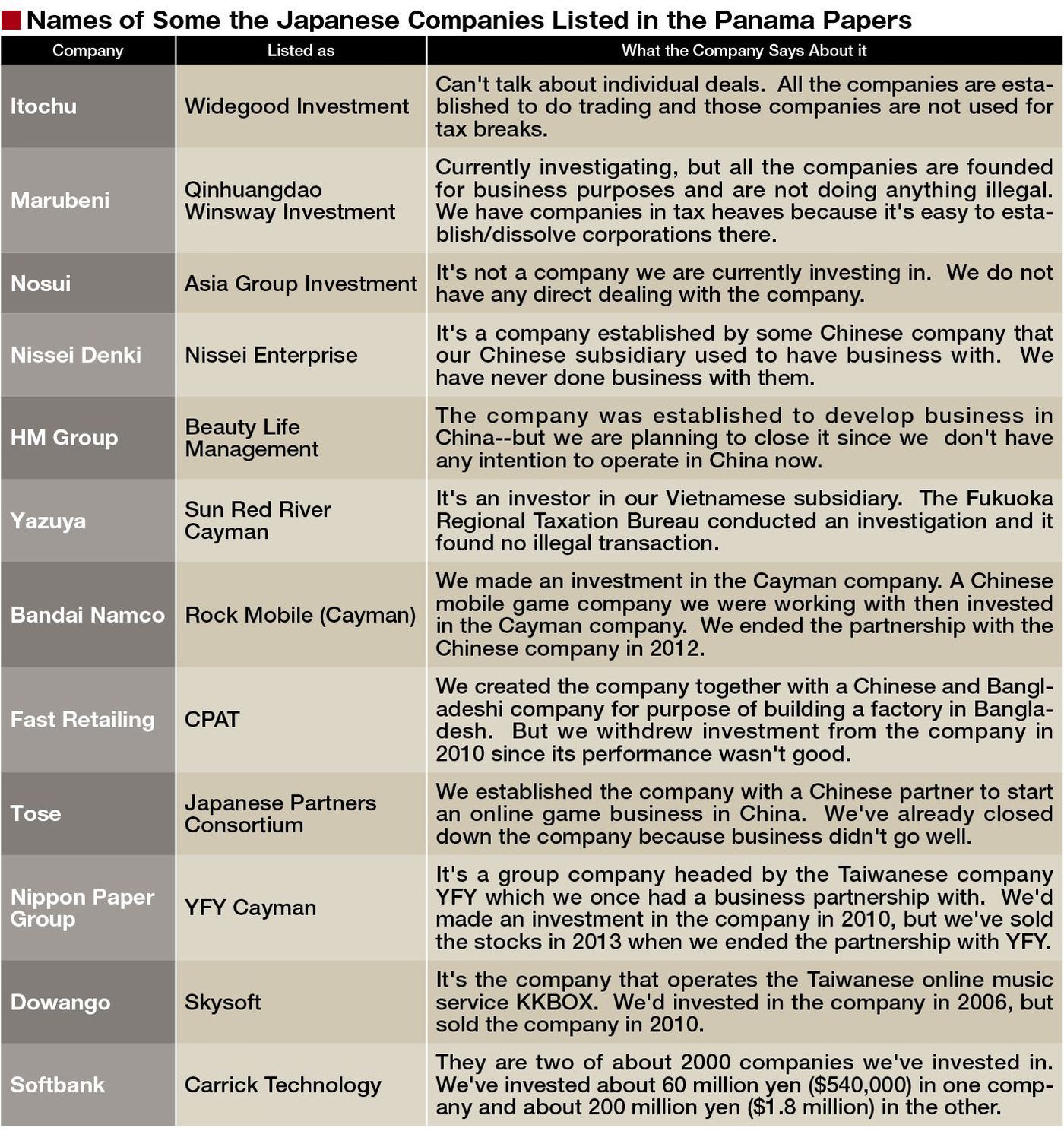

Approximately 400 names on the leaked client list were related to Japanese companies or individuals. All of the companies responded to our inquiry assured that their offshore activities were (or are) appropriately handled under the law, and denied their intention of illegal tax evasion (see below).

If this is true, the obvious question would be: Why did they choose to set up new accounts or business bases in tax havens, of all places? Let’s examine how some Japanese corporate leaders responded.

When Marubeni, a leading Japanese general trading company, searched ICIJ’s updated database, it found the names of eight affiliated legal entities. In a press conference held on May 10 regarding its latest financial reporting, President and CEO Fumiya Kokubu commented, “We confirmed through our internal investigation that all these companies are legitimate.”

The corporation later noted that one of these eight affiliates was set up in 2001 as a bridge company to transfer resources invested in an oil tanking venture that Marubeni jointly established with a Chinese government organization in the ’90s (Marubeni later decided to withdraw from this business).

Since it was difficult to liquidate a joint venture within China, Marubeni needed a legal entity somewhere outside of China to facilitate the withdrawal process; it took until 2005 for Marubeni to pull out all of its assets.

In the case of Nippon Paper, the company invested 100 million dollars (20+% shares) to an offshore holding company called YFY Cayman in 2010. This was a response to the request of parent company YFY, the largest paper manufacturer in Taiwan, with which Nippon entered a strategic business partnership in 2007 to expand its overseas capacity of paperboard and corrugated cardboard production.

But in 2013, Nippon sold all of its YFY Cayman stocks to raise the capital required to reconstruct domestic plants that had been seriously affected by the Great East Japan Earthquake in 2011.

What do individual Japanese investors have to say about using tax havens for their financial activities?

Hiroshi Mikitani, President & CEO of domestic e-commerce major Rakuten, said that, in 1995, he invested approximately 800,000 yen ($7,272) in a foreign investment company that an acquaintance introduced him to prior to founding Rakuten. Mikitani claimed that he has already sold off all the shares he held in this offshore company.

Makoto Iida, co-founder of Secom, the largest private security firm in Japan, explained that the company stock holdings he distributed to offshore entities were all correctly taxed, and that he had already completed the tax payment.

UCC group CEO Gota Ueshima, a member of the founding family of major Japanese brand Ueshima Coffee, simply replied that his offshore financial arrangements are all “strictly for business purposes.”

The Japanese rule

Kaigai Kigyo Soran, published by Toyo Keizai, lists over 100 offshore companies established by Japanese firms in either Panama, the Bahamas, Bermuda, the Cayman Islands, or the Virgin Islands. Some firms, like NYK Line and Kyoei Tanker, have more than 10 offshore companies based in these tax haven countries. SoftBank also invests in a holding company established in the Cayman Islands by Alibaba Group, the largest Chinese e-commerce company.

The Japanese taxation system has a rule that requires domestic companies whose actual tax burden rate of overseas subsidiaries is less than 20% to add the income gained from such subsidiaries to the income of the parent company in Japan.

This rule is intended to prevent Japanese companies from attempting excessive tax avoidance through the establishment of multiple shell entities in tax haven countries as subsidiaries.

In other words, as long as Japanese firms observe this tax declaration rule, they have no reason to be accused of using tax havens for their business activities.

The corporates and individuals that have ties in tax haven countries find them convenient as locations to distribute their assets and wealth, primarily due to the fact that new companies can be easily established and liquidated in tax havens.

Another convenient aspect of tax havens is that that there is no obligation imposed on offshore companies to convene board meetings.

The absence of board members checking business activities on a regular basis can easily make these shell companies a hotbed for money laundering, when operated by the wrong hands.

The Panama Papers have become a timely trigger for the international community to revisit these currently loose regulations in tax haven countries.

When the top leaders of developed nations get together in late May to attend the G7 Ise-Shima Summit, there is a high likelihood that their agenda will include toughening these regulations to address the lack of transparency of money flowing in and out of tax havens.

Indeed, Prime Minister Shinzō Abe spoke to the Budget Committee on May 17, saying, “As the host nation, Japan intends to lead the talks on the prevention of unfair tax evasion across national borders.”

And if the restrictions to use tax havens actually do get stricter, many Japanese firms may be forced to reformulate their overseas strategies.